How to Live (42 page)

Authors: Sarah Bakewell

Having abandoned his city without a fight, Henri III was now a king in exile. He had virtually abdicated, though his supporters still recognized him as their monarch. Guise ordered him to accept the cardinal de Bourbon as his successor; Henri had no choice but to agree. There was no shortage of people ready to point out to him how this disaster had occurred. He had missed his one chance to take Guise out of the picture, either by arresting him or, more conclusively, by having him killed. Montaigne, still a loyal monarchist, joined the king in Charters. When Henri later moved on to Rouen, Montaigne went too. It is not surprising; the alternative would have been to remain with the Leaguists in Paris, or to back out entirely and go home. He did neither, but eventually he did part company with the king and returned to Paris in July 1588. He was ill at the time, being stricken by gout or rheumatism: an attack so bad that he was bedridden during part of his stay.

He would have expected to be left unmolested there, having probably gone for nothing more seditious than a meeting with his publishers—he had recently finished work on his final volume. But Paris was not the right place for anyone associated with the king. While Montaigne was resting in bed one afternoon, still very unwell, armed men burst in and seized him on League orders. The motive may have been revenge for a recent incident in Rouen, when Henri III had ordered the arrest of a Leaguist in similar circumstances: that at least was Montaigne’s theory, as he recorded it in his Beuther diary.

They took him, mounted on his own horse, to the Bastille, and locked him up.

In the

Essays

, Montaigne had written of his horror of captivity:

No prison has received me, not even for a visit. Imagination makes the sight of one, even from the outside, unpleasant to me. I am so sick for freedom, that if anyone should forbid me access to some corner of the Indies, I should live distinctly less comfortably.

To be thrown into the Bastille, especially while ill, was a shock. Yet Montaigne had reason to hope that he would not be there for too long—and he wasn’t. After five hours, Catherine de’ Medici came to the rescue. She too was now in Paris, hoping as usual to sort out the crisis by getting

everyone talking, beginning with Guise, with whom she was in conversation when the news of Montaigne’s arrest arrived. She immediately asked Guise to arrange for Montaigne’s release. With evident reluctance, he complied.

Guise’s orders went off to the commander of the Bastille, but even this did not suffice at first. The commander insisted on having confirmation from the

prévôt des marchands

, Michel Marteau, sieur de La Chapelle, who in turn sent his message of consent via another powerful man, Nicolas de Neufville, seigneur de Villeroy. Thus, in the end, it took four powerful people to get Montaigne freed. His own understanding of it was that he was “released by an unheard-of favor” and only after “much insistence” from Catherine de’ Medici. She must have liked him; the duc de Guise probably didn’t, but even he could see that Montaigne deserved special consideration.

Montaigne stayed in Paris for just a short while after this. The pain in his joints receded, but another illness struck him soon after. It was probably an attack of kidney stones, a condition from which he still suffered with little respite, and which he had so often feared might kill him. On this occasion, it nearly did. His friend Pierre de Brach

described the episode some years later, in a highly Stoic-flavored letter to Justus Lipsius:

When we were together in Paris a few years ago, and the doctors despairing of his life and he hoping only for death, I saw him, when death stared him in the face from close up, push her well away by his disdain for the fear she brings. What fine arguments to content the ear, what fine teachings to make the soul wise, what resolute firmness of courage to make the most fearful secure, did that man then display! I never heard a man speak better, or better resolved to do what the philosophers have said on this point, without the weakness of his body having beaten down any of the vigor of his soul.

Brach’s account is conventional, but it does suggest that Montaigne had, to some extent, come to terms with his mortality since the days of his riding accident. He had been through a great deal since then, and his kidney-stone attacks had forced him into close encounters with death on a regular basis. These, too, were confrontations on a battlefield. Death

was bound to prove the stronger party in the end, but Montaigne stood up to it for the moment.

While recuperating, Montaigne went to see a new friend he had met in Paris the previous year: Marie de Gournay, an enthusiastic reader of his work who invited him to stay with her family at her château in Picardy.

This provided a welcome resting place. In the meantime, the new edition of the

Essays

had come out, and already he was thinking of new additions he would like to make to it, perhaps in the light of his recent experiences. He began adding notes to the freshly printed copy, sometimes alone, sometimes with secretarial help from Gournay and others.

Once he was fully recovered, around November of that year, Montaigne moved on to Blois, where the king was attending a meeting of the national legislative assembly known as the Estates-General, together with Guise. The aim was supposed to be further negotiation, but Henri III had gone beyond that. A king without a kingdom, he was feeling desperate. And he had spent six months listening to advisers remind him that it could all have been different had he wiped Guise out when he had the chance.

Now, with Guise in the Blois castle with him, the opportunity arose again and Henri decided to correct his mistake. On December 23, he invited Guise to his private chamber for a talk. Guise agreed, although his advisers warned him that it was dangerous. As he entered the private room beside Henri III’s bedchamber, several royal guardsmen leaped out from hiding places, slammed the door behind him, and stabbed him to death. Once again, to the shock even of his own supporters this time, the king had gone

from one extreme to another, bypassing Montaigne’s zone of judicious moderation in the middle.

Although Montaigne had come to Blois to join the king’s entourage, there is no suggestion that he knew anything about the murder plot. In the days before the incident, he had been rather enjoying himself, catching up with old friends such as Jacques-Auguste de Thou and Étienne Pasquier—although the latter had the irritating habit of dragging Montaigne off to his room to point out all the stylistic errors in the latest edition of the

Essays

. Montaigne listened politely, and ignored everything Pasquier said, just as he had done with the officials of the Inquisition.

Pasquier, more emotionally volatile than Montaigne, fell into a black depression when he heard about the killing of Guise. “Oh, miserable spectacle!” he wrote to a friend. “I have long been nurturing a melancholic humor within me, which I must now vomit into your lap. I fear, I believe, that I am witnessing the end of our republic … the king will lose his crown, or will see his kingdom turned completely upside down.” Montaigne was not given to such dramatic talk, but he too must have felt shocked. The worst of it, for a

politique

, was that this cold-blooded and mistimed killing threw serious doubt on the moral status of the king, whom the

politiques

considered the focus for all hopes of stability.

Henri III had apparently thought a surgical strike would end his troubles, rather like Charles IX in the run-up to the St. Bartholomew’s massacres. Instead, the death of Guise radicalized Leaguists further, and a new revolutionary body in Paris, the Council of Forty, pronounced Henri III tyrannical. The Sorbonne inquired of the Pope whether it were theologically permissible to kill a king who had sacrificed his legitimacy. The Pope said not, but Leaguist preachers and lawyers argued that any private person who felt suffused with zeal and called to the task by God could do the deed anyway.

“Tyrant” was the word always in the air, but, unlike La Boétie in

On Voluntary Servitude

, the preachers did not call for passive resistance and peaceful withdrawal of consent. They unleashed a fatwa. If Henri was the Devil’s agent on earth, as a flood of propaganda publications now proclaimed, killing him was a holy duty.

The agitation in Paris in 1589 overflowed into every aspect of life. Protestant chronicler Pierre L’Estoile wrote of a city gone mad

:

For today, to mug one’s neighbor, massacre one’s nearest relatives, rob the altars, profane the churches, rape women and young girls, ransack everybody, is the ordinary practice of a Leaguer and the infallible mark of a zealous Catholic; always to have religion and the mass on one’s lips, but atheism and robbery in one’s heart, and murder and blood on one’s hands.

Signs and portents sprang forth everywhere; even Montaigne’s usually levelheaded friend Jacques Auguste de Thou saw a snake with two heads emerge from a woodpile, and read omens into it. Just when the situation looked as if it could get no worse, Catherine de’ Medici died, on January 5, 1589. With his mother gone, Henri III was alone, protected from the hatred around him only by his underpaid troops and those

politiques

who felt obliged to stay on his side as a matter of principle.

As always, it was the

politiques

who attracted everyone else’s distrust. It did not help matters for someone like Montaigne to point out, in cool and measured tones, that the League and the radical Huguenots had now become virtually indistinguishable from each other:

This proposition, so solemn, whether it is lawful for a subject to rebel and take arms against his prince in defense of religion—remember in whose mouths, this year just past, the affirmative was the buttress of one party, the negative was the buttress of what other party; and hear now from what quarter comes the voice and the instruction of both sides, and whether the weapons make less din for this cause than for that.

As for the idea of holy assassination, how could anyone think that killing a king would get one to heaven? How could salvation come from “the most express ways that we have of very certain damnation”?

At some point during this period, Montaigne lost what remained of his taste for politics. He left Blois around the beginning of 1589. By the end of January, he was back in his estate and his library. There, he remained active, liaising with Matignon—still lieutenant-general of the area as well as the new mayor of Bordeaux—but he appears to have sworn off diplomatic traveling from now on. Ironically, just after he gave up, Henri III and Navarre did at last

come to the long-awaited

rapprochement

. They joined forces and prepared to besiege the capital in the summer of 1589.

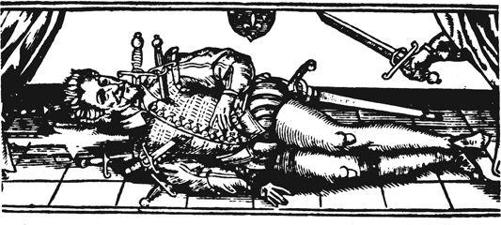

But this was yet another of the king’s mistakes. The Leaguists in the city realized that, with the armies assembling in camps outside their gates, Henri III was within their reach. A young Dominican friar named Jacques Clément received God’s command to act. Pretending to carry a message from secret supporters in the city, he came to the camp on August 1 and was admitted to see the king, who was sitting on the toilet at the time—a common way for royals to receive visitors. Clément pulled out a dagger and just had time to stab the seated king in the abdomen before he himself was killed by the guards. Slowly, over several hours, Henri bled to death. One of his last acts was to confirm Navarre as his heir, though he repeated the condition that Navarre return to the Catholic Church.

News of the king’s death was greeted with jubilation in Paris. In Rome, even Pope Sixtus V praised Clément’s action. Navarre agreed, at last, to revert to Catholicism. At first, some Catholics still refused to recognize him, especially members of the Paris

parlement

, who insisted that Bourbon was their king. For a while, there were two different realities, depending on which side you were on. But slowly, patiently, Navarre won out. He became the undisputed king of France as Henri IV: the monarch who would eventually find a way of ending the civil wars and imposing unity, mostly through sheer power of personality.

He was the king the

politiques

had always hoped for.

Having always had a friendly relationship with Navarre, Montaigne would now find himself drawn again into a semi-official role as adviser to Henri IV—an astonishingly outspoken adviser, as it turned out. Montaigne wrote to Henri to offer his services, as etiquette demanded; Henri responded on November 30, 1589, by summoning Montaigne to Tours, the temporary location of his court. The letter either traveled very slowly, or Montaigne let it sit on the mantelpiece for a long while, for his answer is dated January 18, 1590—too late to obey the command. Allegiance was all right in theory, but Montaigne was determined not to travel, especially as his health was now worse than ever. He explained to the king that, alas, the letter had been delayed; he repeated his congratulations, and said that he looked forward to seeing the king win further support.