How to Live (45 page)

Authors: Sarah Bakewell

The book teeters constantly on the edge of dissolution. Whatever plot

had appeared to be promised at the outset evaporates; the breaks and detours in the narrative take over entirely. “Have I not promised the world a chapter of knots?” Sterne reflects at one point. “Two chapters upon the right and the wrong end of a woman? a chapter upon whiskers? a chapter upon wishes?—a chapter of noses?—No, I have done that:—a chapter upon my uncle Toby’s modesty: to say nothing of a chapter upon chapters, which I will finish before I sleep.” It is like Montaigne on speed.

But of course, says Sterne, no story that really pays attention to the world as it is could be otherwise. It cannot go straight from its starting point to its destination. Life is complicated; there is no one track to follow.

Could a historiographer drive on his history, as a muleteer drives on his mule,—straight forward;—for instance, from Rome all the way to Loretto, without ever once turning his head aside either to the right hand or to the left,—he might venture to foretell you to an hour when he should get to his journey’s end;—but the thing is, morally speaking, impossible: For, if he is a man of the least spirit he will have fifty deviations from a straight line to make.

Like Montaigne on his Italian trip, Sterne cannot be accused of straying from his path, for his path

is

the digressions. His route lies, by definition, in whichever direction he happens to stray.

Tristram Shandy

started an Irish tradition that would reach its most extreme point with James Joyce’s

Finnegans Wake

, a novel which divides into offshoots and streams of association over hundreds of pages until, at the end, it loops around on itself: the last half-sentence hooks on to the half-sentence with which the book began. This is much too tidy for Sterne, or for Montaigne, who avoided neat wrap-ups. For both of them, writing and life should be allowed just to flow on, even if that means branching further and further into digressions without ever coming to any resolution. Sterne and Montaigne both engage constantly with a world which always generates more things to write about—so why stop? This makes them both accidental philosophers: naturalists on a field trip into the human soul, without maps or plans, and having no idea where they will end up, or what they will do when they get there.

JE NE REGRETTE RIEN

S

OME WRITERS JUST

write

their books. Others knead them like clay, or construct them by accumulation. James Joyce

was among the latter: his

Finnegans Wake

evolved through a series of drafts and published editions, until the fairly normal sentences of the first version—

Who was the first that ever burst?

became weird mutants—

Waiwhou was the first thurever burst?

Montaigne did not smear his words around like Joyce, but he did work by revisiting, elaborating, and accreting.

Although he returned to his work constantly, he hardly ever seemed to get the urge to cross things out, only to keep adding more. The spirit of repentance was alien to him in writing, just as it was in life, where he remained firmly wedded to

amor fati:

the cheerful acceptance of whatever happens.

This was at odds with the doctrines of Christianity, which insisted that you must constantly repent of your past misdeeds, in order to keep wiping clean the slate and giving yourself fresh beginnings. Montaigne knew that some of the things he had done in the past no longer made sense to him, but he was content to presume that he must have been a different person at the time, and leave it at that. His past selves were as diverse as a group of people at a party. Just as he would not think of passing judgment on a roomful of acquaintances, all of whom had their own reasons and points of view to explain what they had done, so he would not think of judging previous versions of Montaigne. “We are all patchwork,” he wrote, “and so shapeless and diverse in composition that each bit, each moment, plays its

own game.” No overall point of view existed from which he could look back and construct the one consistent Montaigne that he would have liked to be. Since he did not try to airbrush his previous selves out of life, there was no reason for him to do it in his book either. The

Essays

had grown alongside him for twenty years; they were what they were, and he was happy to let them be.

His refusal to repent did not stop him rereading his book, however, and frequently adding to it. He never reached the point where he could lay down his pen and announce, “Now, I, Montaigne, have said everything I wanted to say. I have preserved myself on paper.” As long as he lived, he had to keep writing. The process could have gone on forever:

Who does not see that I have taken a road along which I shall go, without stopping and without effort, as long as there is ink and paper in the world?

The only thing that stopped him at last was his death. As Virginia Woolf wrote, the

Essays

came to a halt because they reached “not their end, but their suspension in full career.”

Some of this continuing labor may have been in response to encouragement by publishers. The early editions had sold so well that the market for new, bigger, and better ones was obvious. And Montaigne had plenty to add in 1588, after his Grand Tour and his experiences as mayor. He wrote even more in the years after that, when new thoughts must have come to mind following his disturbing experiences at the court of the refugee king: not necessarily thoughts to do with French current affairs, but to do with moderation, good judgment, worldly imperfections, and many of his other favorite themes.

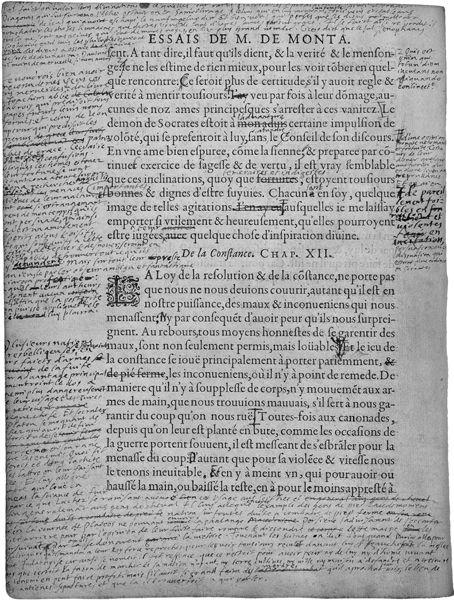

The title page of the 1588 edition, which was published by the prestigious Paris firm of Abel L’Angelier rather than his earlier Bordeaux publisher, presented the work as “enlarged by a third book and by six hundred additions to the first two.”

This is about right, but it underplays the real extent of the increase: the 1588

Essays

was almost twice as long as the 1580 version. Book III added thirteen long chapters, and, of the existing essays in the first two books, hardly any remained untouched.

The new Montaigne of 1588, which hit the world as the real Montaigne was trailing around after Henri III and planning his recuperation with his new friend Marie de Gournay in Picardy, showed a startling new degree of confidence. As befitted someone who rejected the notion of undoing his sins, he was unrepentant about the digressive and personal nature of the book. Nor did he hesitate to make demands on anyone who entered his world. “It is the inattentive reader who loses my subject, not I,” he wrote now, of his tendency to ramble.

The pretense of writing for family and friends alone disappeared; he knew what he had, and scorned any notion of diluting it, hiding it, or streamlining it to fit convention.

A more private kind of writerly self-doubt sometimes afflicted him, all the same. He could not pick the book up without being thrown into creative confusion. “For my part, I do not judge the value of any other work less clearly than my own; and I place the

Essays

now low, now high, very inconsistently and uncertainly.” Each time he read his own words, this mixture of feelings would assail him—and further thoughts would well up, so out would come his pen again.

As the publisher must have expected, the 1588

Essays

found an eager market, although some of the readers who had devoured the 1580 edition as a compendium of Stoic wisdom were taken aback by what they found now. Voices of dissent began to be heard. Was Montaigne, perhaps, getting a little

too

digressive; a little too personal? Was he telling us too much about his daily habits? Was there any relation at all between the titles of his chapters and the material contained within them? Were his revelations about his sex life really necessary? And, as his friend Pasquier suggested when they were together in Blois, might he have lost his grasp of the language itself? Did he realize that his writing was full of odd words, neologisms and colloquial Gasconisms?

Whatever uncertainties Montaigne harbored, none of this touched him greatly. If such criticisms led him to revise anything, it was usually to make it more digressive, more personal, and more stylistically exuberant. During the four years of life that remained to him after the publication of the 1588

Essays

, he continued like this, adding fold upon fold, crag upon crag.

Having given himself a free rein with his 1588 edition, he now galloped away completely. He added no more chapters, but he did insert about a thousand new passages, some of which are long enough to have made a whole essay in the first edition. The book, already nearly twice its original size, now grew by another third. Even now, Montaigne felt that he could only hint at many things, having neither time nor inclination to be thorough. “In order to get more in, I pile up only the headings of subjects. Were I to add on their consequences, I would multiply this volume many times over.” As he had said of Plutarch, “He merely points out with his finger where we are to go, if we like.” Freedom is the only rule, and digression is the only path.

On the title page of one of the copies he worked on, Montaigne wrote the Latin words

viresque acquirit eundo

, from Virgil: “It gathers force as it proceeds.”

This might have referred to how well his book had been doing commercially; more likely, it described the way it had collected material by rolling like a snowball down a hill. Even Montaigne apparently feared that he was losing control of it. When he gave his friend Antoine Loisel a copy of the 1588 edition, his inscription asked Loisel to tell him what he thought of it—“for I fear I am getting worse as I go on.”

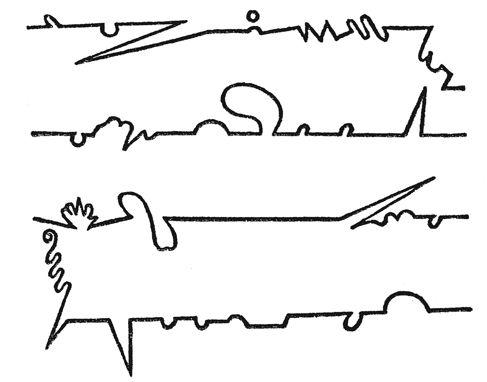

It is true that the

Essays

was beginning to strain at the limits of comprehension. One can sometimes make out the skeleton of the first edition through the tangle, especially in those modern editions which supply small letters to mark out the three stages: A for the 1580 edition, B for 1588, and C for everything after that. The effect can be that of glimpsing the outlines of a Khmer stone temple through a mass of tropical foliage. One can only wonder what a “D” layer might have been like. Had Montaigne lived another thirty years, would he have gone on adding to it until it became truly unreadable, like the artist in Balzac’s “Unknown Masterpiece” who works his painting into a meaningless black mess? Or would he have known exactly when to stop?

There is no way of answering this, but it seems that, at the time of his death, he did not think he had reached that limit yet. His last years of work resulted in at least one heavily annotated copy, which—once it had passed into the hands of his posthumous editor—became the foundation of almost all later Montaigne

Essays

. This editor was none other than that unusual young woman who had entered his life in Paris just as he was finishing his 1588 edition: Marie de Gournay.

DAUGHTER AND DISCIPLE

M

ARIE LE

J

ARS DE

Gournay, Montaigne’s first great editor and publicist—a St. Paul to his Jesus, a Lenin to his Marx—was a woman of extreme enthusiasm and emotion, all of which she uninhibitedly threw at Montaigne on their first meeting in Paris. She became by far the most important woman in his life, more important even than his wife, mother, and daughter, that formidable triad in the Montaigne household. Like all of them, she would outlive him: not surprising, in her case, since she was thirty-two years his junior. They met when Montaigne was fifty-five, and she was twenty-three.