How to Live (38 page)

Authors: Sarah Bakewell

Montaigne also witnessed an exorcism.

The possessed man, who seemed almost comatose, was held down at the altar while the priest beat him with his fists, spat in his face, and shouted at him. Another day, he saw a man hanged: a famous robber and bandit named Catena, whose victims had included two Capuchin monks. Apparently he had promised to spare their lives if they denied God; they did so, risking the loss of their eternal souls, but Catena killed them anyway. Of all the twists Montaigne had yet encountered on the kind of scene that so fascinated him—the vanquished individual who begs for mercy, the victor who decides whether to grant it—this was probably the most unpleasant. At least Catena himself had the courage to die bravely. He made not a sound as he was seized and strangled; then his body was cut into quarters with swords. The crowd were more agitated by the violence done to the dead body, howling at every blow of the sword, than by the execution itself: another phenomenon which puzzled Montaigne, who thought living cruelty more disturbing than anything that could be done to a corpse.

All these were the marvels of modern Rome, but that was not why most sixteenth-century tourists of a humanistic disposition came to the city. They came to absorb the aura of the ancients, and none was more susceptible to this aura than Montaigne, who was almost a native himself. Latin was, after all, his first language; Rome was his home country.

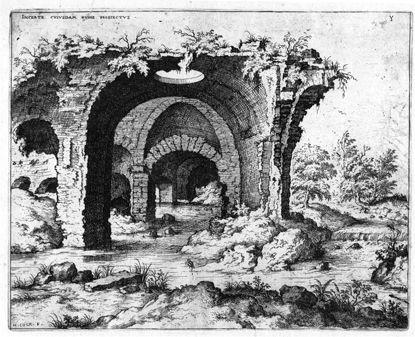

The classical city was very much in evidence all around them, though, for the most part, Montaigne and his secretary did not so much walk

in

the

Romans’ footsteps as far above them. So much earth and rubble had built up over the centuries that the ground level had risen by several meters. What remained of the ancient buildings was buried like boots in mud. Montaigne marveled at the realization that he was often on the tops of old walls, something that became obvious only in spots where rain erosion or the wheel ruts uncovered glimpses of them.

“It has often happened,” he wrote with a shiver of glee, “that after digging deep down into the ground people would come merely down to the head of a very high column which was still standing down below.”

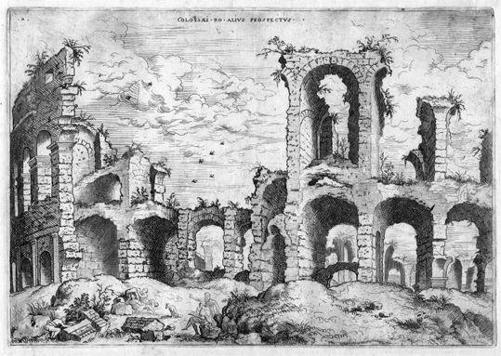

This is much less the case today. Excavation has since freed most of the ruins down to their ankles again, and some have been reassembled. Today, the Arch of Severus soars into the air; in Montaigne’s day, only the upper part of it emerged. The Colosseum was then a jumble of stone overgrown by weeds. Medieval and early modern buildings had also grown over everything; people built on top of ruins or recycled old materials for new constructions. Slabs of stone kept being repositioned at higher levels, to patch up walls or to form shanties. Some areas had been cleared completely to make way for triumphalist projects such as the brand-new church of St. Peter’s. Roman history did not lie in neat strata; it had been repeatedly churned up and rearranged as if by earthquakes.

The result was atmospheric, but it created an impression of ancient Rome to about the extent that a scrambled egg puts one in mind of a freshly laid whole one. In fact, modern Rome had been formed by a similar process to the one Montaigne used to write his

Essays

. Ceaselessly adding quotations and allusions, he recycled his classical reading as the Romans recycled their stone. The similarity seems to have occurred to him, and he once called his book a building assembled from the spoils of Seneca and Plutarch.

In the city, as with his book, he thought creative bricolage and imperfection preferable to a sterile orderliness, and took pleasure in contemplating the result. It also required a certain mental effort, which brought further satisfaction. The experience of Rome that resulted was mainly the product of one’s own imagination. One might almost as well have stayed at home—

almost

, for there was still something unique about being there.

Such a feeling of hallucinatory strangeness frequently strikes visitors to Rome, partly because everything there is already so familiar to the

imagination long before you see it. Two hundred years later, Goethe would find it at once exhilarating and disorienting.

“All the dreams of my youth have come to life,” he wrote on his arrival. “The first engravings I remember—my father hung views of Rome in the hall—I now see in reality, and everything I have known for so long through paintings, drawings, etchings, woodcuts, plaster casts, and cork models is now assembled before me.” Something similar happened to Freud in Athens when he saw the Acropolis. “So all this really does exist, just as we learned at school!” he exclaimed, and almost immediately thereafter felt the conviction: “What I see here is not real.” Montaigne found this meeting between inner and outer versions strange, too, writing of “the Rome and Paris that I have in my soul,” which were “without size and without place, without stone, without plaster, and without wood.” They were dream-images which he compared to the dream-hare chased by his dog.

Rome would bring Goethe an almost mystical peace: “I am now in a state of clarity and calm such as I had not known for a long time.” Montaigne felt this too; despite its touristic frustrations, Italy in general had this effect on him. “I enjoyed a tranquil mind,” he wrote a little later, in Lucca. But he

added: “I felt only one lack, that of company that I liked, being forced to enjoy these good things alone and without communication.”

Eventually leaving Rome on April 19, 1581, Montaigne crossed the Apennines and headed for the great pilgrimage site of Loreto, joining the crowd pouring in procession behind banners and crucifixes.

He left votive figures in the church there, for himself and for his wife and daughter. Then he continued up the Adriatic coast and back across the mountains to a spa at La Villa, where he stayed for over a month to try the waters. As was expected of a visiting nobleman, he hosted parties for locals and fellow guests, including a dance “for the peasant girls” in which he participated himself “so as not to appear too reserved.” He returned to La Villa after a detour to Florence and Lucca, and stayed through the height of the summer, from August 14 to September 12, 1581. His pain from the stone was bad, and he came down with toothache, a heaviness in the head, and aching eyes. He suspected that these were the fault of the waters, which ravaged his upper half even as they helped the bottom half, assuming that they even did that. “I began to find these baths unpleasant.”

Then, unexpectedly, he was called away. Montaigne, who claimed to want only a quiet life and the chance to pursue his “honest curiosity” around Europe, was issued with a long-distance invitation which he could not refuse.

MAYOR

T

HE LETTER ARRIVED

for Montaigne at the La Villa baths, bearing the full weight of remote authority. Signed by all the jurats of Bordeaux—the six men who governed it alongside its mayor—it informed him that he had been elected, in his absence, to be the next mayor of the city. He must return immediately to fulfill his duties.

This was flattering, but, according to Montaigne, it was the last thing he wanted to hear. The responsibilities would be more onerous than those of a magistrate. Demands would be made on his time. There would be speeches and ceremonies—all the things he had least enjoyed about his progress through Italy. He would need his diplomatic skills, for the mayor’s job would mean managing the different religious and political factions in town, and liaising between Bordeaux and an unpopular king. It also meant he had to cut his trip short.

Disillusioned though he was with the spa life, he felt no desire to go home. By now, he had been away for fifteen months—a long time, but not long enough to satisfy him. He seems now to have tried to eke out as many remaining weeks as he could. He did not refuse the jurats’ request, but neither did he hurry back to see them.

First, he traveled back down to Rome, at a leisurely pace, stopping in Lucca for a while and trying some other baths on the way. One wonders why he went to Rome at all, since it meant going over two hundred miles in the wrong direction. Perhaps he was hoping to get advice on whether he could extricate himself from the task. If so, the answer was discouraging. Arriving in Rome on October 1, he found a second letter from the Bordeaux jurats, this time more peremptory. He was now “urgently requested” to return.

In the next edition of the

Essays

, he emphasized how little he had sought such an appointment, and how strenuously he had tried to avoid it. “I excused myself,” he wrote—but the reply came back that this made no

difference, since the “king’s command” figured in the matter.

The king even wrote him a personal letter, obviously intended to be forwarded to him abroad, though Montaigne received it only when he got back to his estate:

Monsieur de Montaigne, because I hold in great esteem your fidelity and zealous devotion to my service, it was a pleasure to me to understand that you were elected mayor of my city of Bordeaux; and I have found this election very agreeable and confirmed it, the more willingly because it was made without intrigue and in your remote absence.

On the occasion of which my intention is, and I order and enjoin you very expressly, that without delay or excuse you return as soon as this is delivered to you and take up the duties and services of the responsibility to which you have been so legitimately called. And you will be doing a thing that will be very agreeable to me, and the contrary would greatly displease me.

It seemed almost a punishment for being so little given to political ambition—assuming that Montaigne’s protestations of reluctance were true.

His lack of haste in getting home certainly does not suggest a greed for power. Still taking his time, he meandered towards France via Lucca, Siena, Piacenza, Pavia, Milan, and Turin, taking around six weeks to make the journey. As he crossed into French territory, he switched back from Italian to French in the journal, and when at last he reached his estate he recorded his arrival together with a note that his travels had lasted “seventeen months and eight days”—a rare case of his getting a precise figure correct.

In his Beuther diary, he also wrote a note under the date November 30: “I arrived in my house.” He then presented himself to the officials of Bordeaux, obedient and ready for duty.

Montaigne would be the city’s mayor for four years, from 1581 to 1585. It was a demanding job, but not an entirely thankless one. It came with honors and trappings of all kinds: he had his own offices, a special guard, mayoral robes and chain, and pride of place at public functions. The only thing he lacked was a salary. Yet he was more than a figurehead. Together with the jurats, he had to select and appoint other town officials, decide civic laws, and judge court cases—a task Montaigne found especially difficult to fulfill

to his own high standards of evidence. Above all, he had to play the politics game, with care. He had to speak for Bordeaux before the royal authorities, while conveying royal policy downwards to the jurats and other notables of the city, many of whom were set on resistance.

The previous mayor, Arnaud de Gontault, baron de Biron, had upset many people, so another of Montaigne’s early tasks was to smooth over the damage. Biron had governed strictly but irresponsibly; he had allowed resentment to develop between various factions, and had alienated Henri of Navarre, the powerful prince of nearby Béarn—a person with whom it was important to maintain good relations. Even Henri III himself had taken offense at Biron’s obvious sympathy for the Catholic Leaguists, who were still rebelling against royal authority. Contemplating Biron makes it apparent why the city chose Montaigne to succeed him: they now had a new mayor known for his moderation and diplomatic skills, the very qualities Biron lacked. In particular, although Montaigne was affiliated with the despised

politiques

, he knew how to get on with everyone. He was known as a man who would listen thoughtfully to all sides, whose Pyrrhonian principle was to lend his ears to everyone and his mind to no one, while maintaining his own integrity through it all.