How to Host a Dinner Party (16 page)

Read How to Host a Dinner Party Online

Authors: Corey Mintz

It’s pretty embarrassing to clink a fork against a wine- glass, demand the floor, and address everyone as “ladies and gentleman,” only to oversell a roast beef that you’ve burned. I once had a host include salt and pepper in his explanation of his dish. Please err on the side of brevity. Do not list every last ingredient down to the microscopic level. We know that the dish contains both protons and electrons.

If you are serving confit lamb shoulder with a parsnip purée, jus, and whisky-soaked apricots, try introducing it as “lamb, parsnip, and apricot.” This gives your guests the opportunity to discover the depth of flavours and textures on their own, and, if they desire, to ask questions about how it was made.

TECHNOLOGY AT THE TABLE

Some guests will ask for a phone charger, terrified that they’ll miss a text from a friend who is glued to tonight’s episode of

Some guests will ask for a phone charger, terrified that they’ll miss a text from a friend who is glued to tonight’s episode of

America’s Somethingest Something

. Some people plop their phone down next to the plate, as if it were part of the cutlery set. Others are aghast if anyone looks at their phone or if it rings, even in silent mode.

There’s no definitively final word on cellphone use at dinner other than the obvious conclusion that it’s rude. At my table, I don’t mind phones for the purpose of settling disputes, but other than as a pocket-sized encyclopedia, I don’t want to see one in use.

The ways that we interact with technology have changed. We share information differently than we used to. Let’s be honest about that. Most people do not own dictionaries or encyclopedias anymore. Settling a bet by looking up facts is a perfectly good use for a smartphone.

However, I had a pair of dinner guests who introduced me to the Challenge of Three. If a fact is disputed at the dinner table, make three attempts to solve it before using Google. Call a friend, look it up in a book (gasp), or use deductive reasoning. I know this sounds like rubbing two sticks together to make fire, but when you avoid the shortcut of reaching directly for the easy answer, you’ll find yourself connecting with people in a more active, meaningful way. The dudes who suggested this rule were engineers. So they did have an obsessive interest in problem solving.

The only people allowed to put their phones on the table are doctors who are on call. And parents with children under ten month old. Everyone else should keep it in their pants. There are very few emergencies in this life. Most of them can wait for an hour. A lot of parents like to claim their need to be available to the babysitter as an excuse to keep checking their phones, but I’ve seen these same people pretend to check in with the sitter and then tell me who’s winning the hockey game.

Our dinner mates should not have to compete with a glowing screen for anyone’s attention. Smartphones are just the current example of a recurring conflict. This includes phones, televisions, computers, and whatever else humanity is likely to create, whatever new devices will make our lives easier but will cause us to miss out on more basic human experiences.

I’ve accepted that life has become more digital and less personal, but when we are gathered with friends, we take a break from the daily world of the short attention span where every movie ever made becomes boring because we can download another one in five minutes.

We need not be distracted by every hyperlink that pops into our head. Just because you saw a funny video on the Internet doesn’t mean that everyone at the table needs to see it. If you cannot tell the story without displaying the video, perhaps it’s not worth telling. And even if others do want to see it, consider how it affects the evening.

When a group is sitting across from each other, making eye contact, listening, and arguing, people are active. When you insist on showing everyone something on your phone — a cat that looks like Hitler, your child’s first steps, a parody of the pop culture thing you’ve been talking about — you’re asking them to switch into the passive mode and then jump back into the social one. Think about how people behave in a movie theatre after the lights come back on. They’re dazed, blinking, unresponsive. They need a walk to the parking lot to jog their conversational muscles.

At all costs, prevent your guests from staring at a glowing screen. If you have a friend who is a particularly bad offender, you are within your rights to confiscate the device at the beginning of the evening.

THE PRESENTATION

Yes, good food is more important than good-looking food, but this isn’t a cafeteria. Even simple food — a bowl of soup or a plate of sliced steak with potatoes — deserves to be served with respect.

Yes, good food is more important than good-looking food, but this isn’t a cafeteria. Even simple food — a bowl of soup or a plate of sliced steak with potatoes — deserves to be served with respect.

Soups need garnishes. And it need not be a butter-poached lobster tail (though no one would complain about that). Something as simple as a sprinkling of crushed nuts, seeds, or quinoa with a drizzle of olive oil can make a huge difference.

Plates should be clean. If a plate has a rim, that is where the food stops. Roll up a cloth, wrap it in elastic bands and wet it. Use the roll to wipe sauce spills from the rims of plates before serving them. Drips on the plate’s edge — a natural result of transferring, say, freshly sliced pieces of rare beef from the cutting board — look messy. No one would ever remark on it, the way that no one would complain about an A grade. But if an A+ can be had by taking a second to wipe the plate, why not go for the bonus marks? Most guests wouldn’t even register messy plates, at least on a conscious level. But cleanliness makes an impression.

If, while you’re carrying plates to the table, food falls over or sauces slide, let it go. Yes, in a high-end restaurant, if the chef’s stack of polenta fries topples, servers will return to the kitchen for a re-plate. At home, this is a step too far. Going back to your kitchen to re-plate food will make it look like you’re trying way too hard. If I make a mess on the way to the table, or if I notice at the last minute that a plate is chipped, then that’s the plate that I serve to myself.

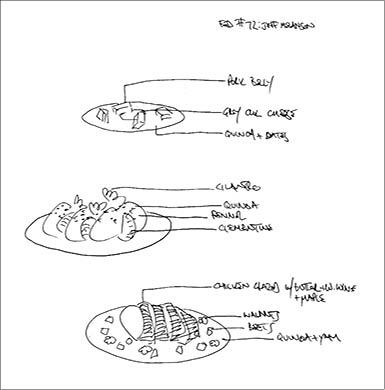

Plate Design

How the food will look is something you considered back in the planning stage (see Chapter Two). If you’ve sketched out your meal, snap it on the fridge with magnets. Consult your drawings before each course, so that you don’t forget key ingredients.

Stay away from square plates. A square is a fine shape, perfectly suited to the spaces on a tic-tac-toe board, Japanese watermelons, or, in a forgotten era, televisions. Even if objects within that space are not consciously placed in one of four quadrants, something about a square frame for this purpose feels off. If this book were a square, it would fail to impart the serious tone of its contents. Stick with circles and rectangles. When assembling a dish, try to focus your food in the centre. Don’t worry so much about elements overlapping. It will look cleaner and more appetizing when it’s clustered, rather than spread out. It will also retain heat better.

On the subject of volume, try to stick to your plan. It’s to your advantage to make too much of everything, but not to dole it all out. Whether it’s tomato sauce on spaghetti or jus on lamb, there can be too much of a good thing. The mistake that a lot of people make is to distribute what they have proportionately, rather than execute the plate design from their plans. No one does this on purpose. It’s more like that time you tried to even out your sideburns and ended up bald. What happens is that the cook portions the food out, then sees how much is left, and proceeds to dump sauce on all the plates to use it up. Only after it’s done does the cook look at the soupy mess and realize that it isn’t what they intended.

If there is supposed to be a streak of jus next to the slices of lamb, make that streak on each plate even if you have enough jus for two, or three, or four tablespoons. If people rave about the sauce, serve them more. It’ll be a nice surprise that you have more in the pot.

Now, about those streaks. Chefs have a number of tools in specific shapes for getting food onto the plates: squeeze bottles, piping bags, metal moulds, stencils. But they also have technique that, like any artist, they’ve perfected over years of repetition and experimentation. Their work cannot be replicated simply by buying their tools any more than purchasing a basketball will enable you to dunk. Nor should this be your goal.

You want to brush a perfect rectangle of your cumin/raisin purée on the bottom of the plate? For the lamb? Where do you think you are? Is there a camera crew behind you? Are your guests paying $150 each? No. You are at home. And to be at home, with your friends, and think it is a good use of your time to hunch over the kitchen counter painting sauce onto a plate with a stencil and brush is to misunderstand the very nature of the dinner party.

Those streaks, where the sauce is a sort of fat blob at one end, and trails off to nothingness as it rides the curve of the plate, are literally all in the wrist. I can write the directions plainly enough: tip a spoonful of sauce to the plate and, in one smooth motion, drag it across the surface, lifting up at the end. But those are just words and the method is all about motion, having a confident, relaxed wrist, and having repeated the gesture a hundred times. Speed is important. Your lines must be assured and fluid. Slowly dragging the tip of the bottle or spoon against the plate will result in a bumpy, uneven line. You must practise this. There is no other way to learn.

The next time you’re cooking a pot of tomato sauce, grab a spoon and a plate and practise saucing. Notice how the liquid spreads differently when poured directly, versus when it’s zipped across the surface of the plate, and how it acts differently depending on if it’s thick or thin. Notice how it splatters when poured from high. Take that into consideration when you’re ladling soup. Do not ladle from an arm’s reach away like some cocktail cowboy bartender. Bring the ladle to the bowl and tip it gently.

Balance

Good food has some balance of flavour and texture. This gives our palates the variety we crave, and the contrast highlights the dish’s qualities (e.g., smoothness and crunchiness are more pronounced when paired together). This is why soup is simultaneously comforting and boring. Meals should not be monotonous. Consider the four food groups, and that vegetables are usually under-represented.

Good-looking food has some balance of shape and colour. I once worked for a chef whose solution to this was to sprinkle a handful of beets, ground in a food processer. It looked like Doc Holliday had coughed on the plate. Please don’t add anything only for the sake of appearance. Everything should be there because it tastes good.

We love crunchiness. If you use it as an adjective on any restaurant menu, that will likely be the top-selling item. But if you used it for every dish, it would lose its power. Crunchiness is usually achieved through deep-frying, which is not so hard to do at home in a pot, but during dinner it becomes a hassle to deep-fry safely. Some thin items — such as basil, garlic, or chicken skin — can be deep-fried a few hours ahead of time and they will have a big impact as a garnish. Crunchiness could also be something as simple as adding crushed cashews to a bean salad.