Hitler's Final Fortress - Breslau 1945 (2 page)

Read Hitler's Final Fortress - Breslau 1945 Online

Authors: Richard Hargreaves

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Germany, #Military, #World War II, #Russia, #Eastern, #Russia & Former Soviet Republics, #Bisac Code 1: HIS027100

Introduction

O

n a summer’s day in Wrocław, take a stroll along

Ulica

Marie Curie Sklodowskiej – Marie Curie Sklodowskiej Street. Modern ‘bendy buses’ with TV screens and electronic ticket machines vie for room on the suburban boulevard with clapped-out yellow coaches and trams which trundle east and west at regular intervals. After ten or so minutes you will cross the

Most

Zwierzyniecki – Zwierzyniecki bridge – which spans one of the countless arms of the Oder. It has stood here since 1897 – there is an inscription celebrating the toil of the men who spent two years building it. But like all traces of the city’s Germanic past, the plaque above the dateline has gone. Less easy to erase are the traces of battle; as with many of Wrocław’s Oder crossings, Most Zwierzyniecki, is scarred by the bullets which struck it in the spring of 1945. Across the bridge you enter a district of avenues lined by trees. Ulica Marie Curie Sklodowskiej becomes Ulica Zygmunta Wróblewskiego – the fourth title it has enjoyed in a century. On your right are the zoological gardens, on your left Ulica Adama Mickiewicza. Follow it for 150 yards until the trees part, revealing an alley leading to one of Wrocław’s jewels:

Hala Ludowa

– the People’s Hall – Max Berg’s imposing colosseum of concrete and steel, built in 1913 to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the German people breaking the shackles of Napoleonic rule. Tall columns, their plinths empty, lead down a sprawling concourse, dominated by a gigantic metallic spike or spire, the

Iglica

, erected in 1948 to celebrate Silesia’s ‘return’ to Poland. To the left is a four-domed exhibition hall, latterly home to the

Wytwórnia Filmów Fabularnych

– the factory of feature films. Four concrete modernist statues stand guard in front of it. The entrances are barred, the doors obliterated by Polish graffiti. The portico’s cracked tile floor is covered with leaves, cigarette ends, sweet wrappers and other detritus. At one end of this seemingly forgotten porch is a huge tablet in a wretched state of repair, honouring the deeds of Polish soldiers who marched westwards with Soviet troops in 1944 and 1945 from the Bug to the Vistula, through Warsaw, through Pomerania, across the Oder and Neisse, and finally into Berlin. Turn around and you will find another huge stone inscription. A helmet adorned with a Red Star sits on a laurel wreath, chipped and discoloured, stained by more than six decades’ exposure to the elements. Beneath it a litany of Red Army victories: Moscow, Stalingrad, Kursk, Leningrad, the Ukraine, Byelorussia, Warsaw, Budapest and Bucharest, Belgrade, Vienna, Prague, and Berlin among them, plus the name of this city, Wrocław. Like every monument, memorial and grave for the fallen of 1945, the gigantic tablets in the grounds of the Hala Ludowa are crumbling, decaying, overgrown, unloved, forgotten.

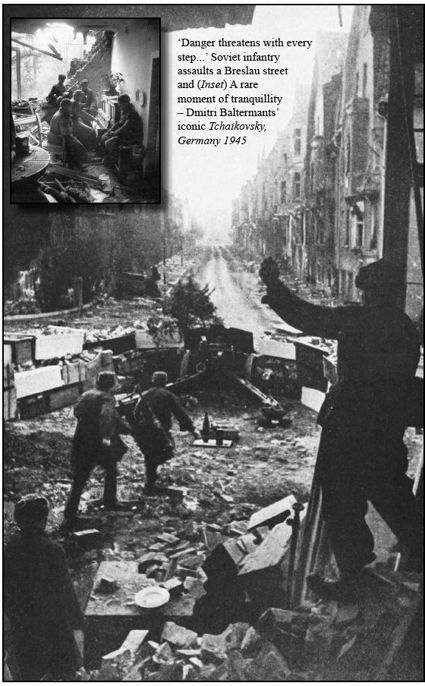

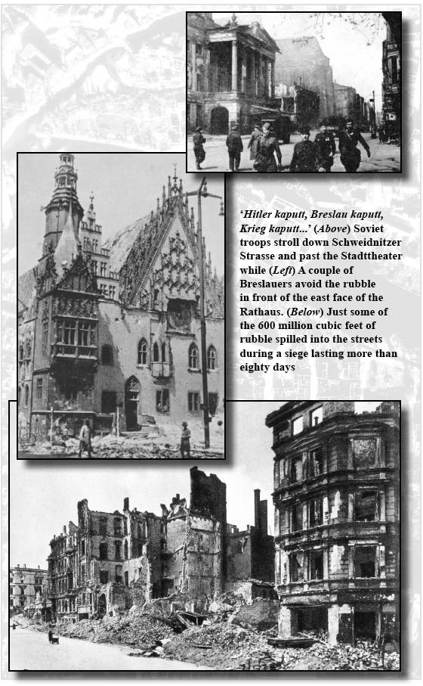

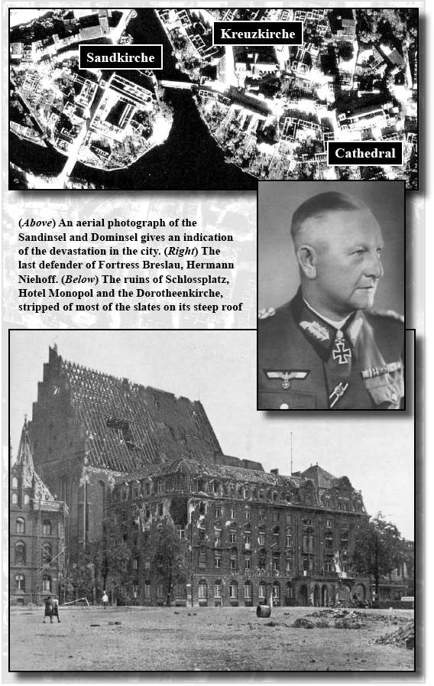

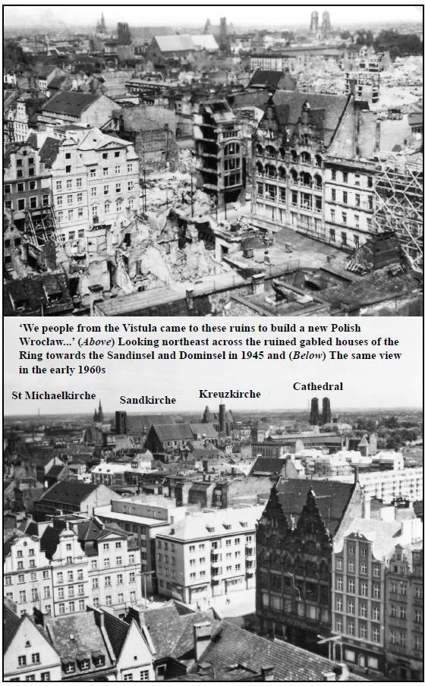

For once a terrible battle raged for this city. The siege of Breslau – as it was then – lasted longer than the battle for any other German city in 1945. The city was encircled for longer than Berlin (ten days), Budapest (sixty days), even Stalingrad (seventy-three days). It is a struggle which came to naught for the defenders. It achieved nothing, save to reduce a city, which was barely touched by war as 1945 began, to a ruin by the time it surrendered on May 6th. The devastation wrought was greater than in the German capital, greater than in Dresden – that byword for destruction in World War 2 – and as great as in Hamburg, another metropolis laid waste by Allied bombers.

*

At least 18,000 of Breslau’s population died in less than one week, fleeing the advancing Red Army in the depths of winter. A further 25,000 people – soldiers, civilians, foreign labourers, prisoners – were killed during the twelve-week struggle for Breslau. Nor does the story – or the suffering – end with the city’s fall. For the German survivors, bitter fates awaited: for the soldiers, prison camps in the Soviet Union; for civilians, rape, plunder and starvation, and finally expulsion from their homes as Silesia became Polish and Breslau became Wrocław. For Polish settlers – many driven from their homeland like the Germans they displaced – there were decades of toil and hardship as they struggled to rebuild the Silesian capital.

They succeeded. Today Wrocław is a flourishing city once more, the fourth largest in Poland, its war-scarred landscape cleared, its battle-scarred buildings restored and rebuilt. It is a seat of learning, the heart of Poland’s electronics and rail industries, a centre of banking and finance, a destination for hundreds of thousands of tourists every year. Most of these visitors are oblivious to the bitter struggle for Breslau.

The actors may be bit-part players compared with those at the fall of Berlin, the stakes not as high as at Stalingrad, the suffering not as protracted as in Leningrad, but the siege of Breslau is terrible, if compelling, drama. For the sake of the men and women involved on all sides it is a story which deserves to be told.

Gosport, November 2010

*

Around one in five buildings in Berlin was destroyed during the war; the figure in Dresden was double that; some two in every three homes in Hamburg and Breslau were uninhabitable; the heart of Aachen lost four out of five homes; and in Cologne, an estimated ninety-five per cent of the old town was destroyed.

Acknowledgements

N

o-one can embark upon researching the fall of Breslau without consulting two seminal works. Horst Gleiss’s monumental

Breslauer Apokalypse

and the thousands of documents and testimonies it contains is a project unique in the history of World War II; it forms the kernel of this book. Similarly, Norman Davies and Roger Moorhouse’s

Microcosm

is a wonderful biography of Breslau/Wrocław, which is as balanced as it is illuminating. Jan-Hendrik Wendler deserves special mention for providing documents relating to Schörner’s Army Group and obscure German unit histories. Elsewhere, the staff of the Bundesarchiv in Freiburg proved as helpful as ever, as did the staff of the Department of Documents at the Imperial War Museum, London; the Public Record Office, Kew; the following libraries: University of Nottingham, University of Manchester, University of Sussex, University of Portsmouth, University of Warwick, and Lancashire, Portsmouth, and Nottinghamshire; New York Public Libraries; British Newspaper Library. I would also like to thank: Jason Pipes and his colleagues at

www.feldgrau.net

; Michael Miller for his help with Karl Hanke’s biography; Howard Davies for his inestimable knowledge of the German language; Matt Abicht for rare aerial photographs of the battle; Andy Brady for the maps; Tom Houlihan, Bill Russ, Yan Mann, Darren Beck, for proofreading, advice, and occasional moral support. The book which follows is all the richer for their input. For any mistakes, I alone bear responsibility.

Abbreviations Used in References

| AOK | Armeeoberkommando – staff of an army in the field |

| BA-MA | Bundesarchiv-Militär Archiv – Bundesarchiv Military Archive, Freiburg |

| Div | Division |

| DDRZW | Das Deutsche Reich und der Zweite Weltkrieg |

| Documenty | Festung Breslau: Documenty Oblezenia 16/2-6/5/45 |

| HGr | Heeresgruppe – Army Group |

| IMT | International Military Tribunal |

| IWM | Imperial War Museum, London |

| Kdo | Kommando – command |

| KTB | Kriegstagebuch – war diary |

| NA | National Archives, Kew |

| NMT | Nuremberg Military Tribunal |

| OKH | Oberkommando des Heeres – German Army High Command |

| OKW | Oberkommando der Wehrmacht – German Armed Forces High Command |

| Pz | Panzer |

| SD Meldung | Sicherheitsdienst – SS Security Service – report |

| TB Cohn | Diary of Willi Cohn |

| TB Goebbels | Diary of Joseph Goebbels |

| TB Oven | Diary of Wilfred von Oven |

| Vertreibung | Dokumentation der Vertreibung der Deutschen aus Ost-Mitteleuropa I, Die Vertreibung der deutschen Bevölkerung aus den Gebieten östlich der Oder-Neisse |

Author’s note

German ranks throughout, with the exception of

Generalfeldmarschall

(field marshal), have been left in their original language. An explanation of the comparative ranks can be found in the appendix. The names of towns, villages, streets and buildings in Silesia retain their German names for events prior to their becoming Polish; thereafter they revert to their post-1945 Polish names.