History Buff's Guide to the Presidents (36 page)

Read History Buff's Guide to the Presidents Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #United States, #Leaders & Notable People, #Presidents & Heads of State, #U.S. Presidents, #History, #Americas, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Reference, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #Political Science, #History & Theory, #Executive Branch, #Encyclopedias & Subject Guides, #Historical Study, #Federal Government

Before becoming president, Gerald Ford was a member of the Warren Commission that investigated the John F. Kennedy murder.

9

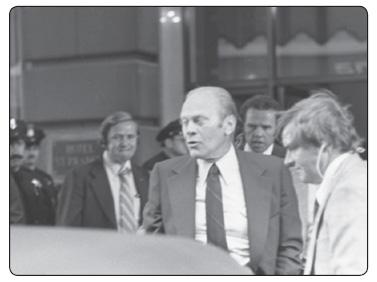

. GERALD R. FORD (SEPTEMBER 22, 1975)

Once again it would be a woman, and again in California, but this time the gun would go off. Despite his brush with the Manson family not three weeks previous, Ford refused to alter his hectic travel schedule, which had taken him to thirty-nine states in his first thirteen months in office. “I have no intention to allow the Government of the people to be held hostage at the point of a gun,” said Ford, although he started wearing a cumbersome bulletproof vest on public outings and allowed a larger contingent of personal bodyguards. Subconsciously, he began to look at hands before shaking them.

159

Of all the types Ford might have suspected, the likes of Sara Jane Moore was probably not among them. Forty-five years old, mother of four, trained in nursing and accounting, her hobbies included reading, needlework, and going to the opera. With a submissive countenance and dozy brunette waves, Moore had the look of a careworn housewife. Her past, however, was anything but docile.

160

Estranged from an authoritarian father, she married and divorced five men, abandoned three of her four children, bounced from job to job, and became enamored by the radical fringe within San Francisco. Finding acceptance within several militant organizations, Moore gained enough access to merit the attention of the FBI.

In 1974, the FBI convinced her to become an informant. Flattered and willing, she accepted. But in her services, Moore began to fear the clandestine government rather than the younger, idealistic people she was encountering. She admitted to a friend her involvement with the FBI and was immediately ostracized by the counterculture community. Hoping to regain their trust, she contemplated shooting Ford, against whom she had no particular animosity. Not a natural-born killer, Moore actually phoned local police, admitting she was thinking of harming the president. Officers interviewed her, confiscated a .44-caliber pistol, and informed the Secret Service of her identity and Bay Area address. In light of her complicity, officials did not consider Moore a threat.

161

Ford came to San Francisco soon after. One stop included a press conference at the St. Francis Hotel. Standing patiently in a crowd outside was Moore, with a new .38-caliber Smith and Wesson revolver tucked in her purse. Moore later claimed she debated whether to wait for her target or to pick up her son from school. The answer came when Ford walked out of the hotel. Moore brandished her weapon and pulled the hammer back. A bystander knocked her arm astray just as she squeezed off a single round.

Once again, Ford remained relatively unfazed. Interviewed afterward, he pledged to remain accessible to the people, insisting, “If we can’t have that opportunity of talking with one another, seeing one another, shaking hands with one another, something has gone wrong with our society.”

162

In rebuttal, the disillusioned Moore offered her own commentary: “There comes a point when the only way you can make a statement is to pick up a gun.”

163

Seventeen days after the first attempt on his life, a second would-be assassin stalked Ford. The photographer caught the president reacting to the sound of the gunshot emanating from the .38 Smith and Wesson of Sara Jane Moore.

Gerald R. Ford Library

Both Lynette Fromme and Sara Jane Moore were sentenced to the federal prison at Alderson, West Virginia, from which both briefly escaped (Moore in 1979 and Fromme in 1987).

10

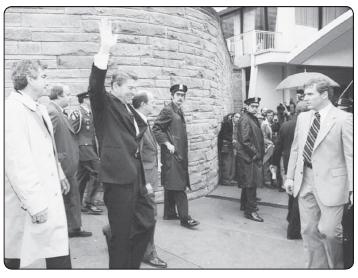

. RONALD REAGAN (MARCH 30, 1981)

A bulletproof car nearly cost him his life. As Ronald Reagan stepped out of the Washington Hilton Hotel and greeted the small crowd outside, his ten-week stint as chief executive almost came to an abrupt end. In the span of two seconds, a sometimes psychiatric patient, John Hinckley Jr., littered the cool gray afternoon with a spray of six bullets. Every shot missed the intended victim—until one struck the right rear panel of the armored limousine, flattened to the size of a dime, ricocheted at a sharp angle, and spun straight into the president’s chest.

Reagan waves to the crowd seconds before John Hinckley Jr. sprays the area with bullets. A ricochet struck Reagan in the chest. Press Secretary James Brady, to the left and behind the president, was hit in the brain and mistakenly reported as dead after the shooting. Brady actually survived but never walked again under his own power.

Ronald Reagan Presidential Library

Rushing to evacuate Reagan from the area, Secret Service agent Jerry Parr shoved him into the waiting car, driving his chest into the transmission hump with such force that Reagan was said to have yelled, “You son of a bitch, you broke my ribs.”

164

Reagan started to cough up a bloody froth, suggesting that a cracked bone had indeed pierced a lung. Quickly examining his charge, Parr noticed a small slit in the president’s chest near the left arm and ordered the driver to nearby George Washington Hospital at maximum speed.

Back at the crime scene, officials had thrown down and rapidly disarmed the shooter, while others treated the injured. Agent Tim McCarthy and police officer Thomas Delehanty were seriously wounded. P

RESS

S

ECRETARY

James Brady lay immobile. He had taken a bullet to the brain. National media would soon report that Brady had died.

Blocks away, Reagan walked into the hospital and then collapsed, unable to breathe. He had lost nearly half his blood. The jagged, spent round had lodged within an inch of his seventy-year-old heart.

165

Remarkably, every one of Hinckley’s victims survived. Reagan was in and out of surgery in less than an hour. Brady, however, sustained severe cerebral damage, leaving him confined to a wheelchair for the remainder of his life.

Stories of Reagan’s calm demeanor and bright banter while going into surgery (along with less-publicized moments of genuine fear) endeared him to the American public. A rapid recovery also dispelled trepidations of his advanced age, and he experienced a surge of popularity.

Amid all of this was a strange underlying thread of pop culture. Hinckley later confessed he had shot the president, a former actor, in order to impress an actress he had seen in

Taxi Driver

, a film about a misguided would-be assassin.

In spite of his brush with death, Reagan continued to support the sale and ownership of personal firearms, whereas his severely disabled Press Secretary successfully lobbied for greater gun control, later earning him the Presidential Medal of Freedom from William Clinton.

Seven months after the attempt on Reagan’s life, Egyptian president Anwar Sadat was gunned down in Cairo. For security reasons, Reagan refused to have himself or Vice President George Bush attend the funeral. He instead sent former presidents Richard Nixon, James Carter, and Gerald Ford.

Harry Truman was once asked how foreign policy was formed in the federal government. He answered with his typically abrupt candor, “I make foreign policy.” Contrary to Truman’s assertion, the variables involved in shaping international relations are infinite and ever changing. It is for that very reason that presidents create, and their publics prefer, statements clarifying their position. Such pronouncements establish the impression of leadership, a character trait considered vital for presidential and national success. By the twentieth century, these mission statements became known as “doctrines.”

1

Latin for “belief code,” a doctrine is usually traced to a particular presidential speech or resolution. Often presented as a sweeping plan for the future, it is always a response to a recent event and aimed squarely at a particular country or ideology. Almost every doctrine has been totally baseless in international law, claiming jurisdiction far beyond the boundaries of the United States.

The fact that most have come from recent administrations is a testament to the growing American presence in every comer of the world—politically, commercially, militarily. And rather than being buried in some secret document or clandestine backroom deal, they acquired their authority through congressional acts and popular appeal. With very few exceptions, the following declarations enjoyed a solid base of support when they were unveiled.

Listed here in chronological order are the most prominent doctrines of administrations past. They reveal a country eager from its infancy to police large portions of the globe. They also attest that presidents have been stalwart in their resolutions but extremely selective in their actions.

1

. MONROE DOCTRINE (1823)

James Monroe’s seventh annual message to Congress was a rather dreary report, save for a pair of deafening thunderclaps. In a doctrine likely authored by Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, the president issued two clear warnings. First, Europe was not allowed to colonize any part of the Western Hemisphere ever again. Second, any attempt to do so would be considered a direct threat to the security of the United States.

Monroe’s audacity came from two principle events—revolution in the Americas and counterrevolution in Europe. By 1822, nearly all of Central and South America had won independence from Spain and Portugal. Meanwhile, the old monarchies had successfully crushed Napoleon Bonaparte and were looking to expand imperial footholds overseas. Britain already held Canada and much of the Caribbean, Russia laid claim to Alaska and much of the Pacific Northwest, France had its French Guyana, and Spain (the biggest loser in the revolutions) wanted to revitalize its fading imperial greatness.