History Buff's Guide to the Presidents (31 page)

Read History Buff's Guide to the Presidents Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #United States, #Leaders & Notable People, #Presidents & Heads of State, #U.S. Presidents, #History, #Americas, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Reference, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #Political Science, #History & Theory, #Executive Branch, #Encyclopedias & Subject Guides, #Historical Study, #Federal Government

Clinton v. Jones

did not go well for either party. Clinton paid a settlement of nearly one million dollars, had his law license suspended, and was impeached for statements made during deposition. Jones underwent a divorce, posed nude in

Penthouse

, and took part in a celebrity boxing match to pay for legal expenses.

Two little boys were playing with a toy soldier when they decided it would be fitting and proper to execute him because he had been sleeping on guard duty. While they began to dig his final resting place in the lawn, the family gardener commented that perhaps forgiveness was in order. Not long after, a note arrived from the boys’ father: “The doll Jack is pardoned. By order of the President. A. Lincoln.”

102

Article 2, section 2 of the U.S. Constitution gives each chief executive “Power to grant Reprieves and Pardons for Offences against the United States, except in Cases of Impeachment.” To date, more than ten thousand people—plus the aforementioned Jack—have received presidential pardons. Thousands more have attained commutation of sentences, remissions of fines, and general amnesties. Their crimes, alleged and proven, have covered the spectrum, from tax evasion and gaming violations to perjury, drug trafficking, murder, military desertion, espionage, and treason.

Among the few powers explicitly granted to the executive, clemency is the only one that is irreversible, and yet it is the least analyzed. Even the Philadelphia Convention barely expressed concern when giving presidents the ability to place almost anyone above the law. Their rationale stemmed from tradition, as several governors already had the authority (a holdover from the English monarchy). They also viewed clemency as a tool of prudent peacekeeping rather than a weapon of tyranny.

Over the years, the Founding Framers have been correct, generally. Most clemencies transpire quietly, often at Christmastime, with minimal notice or opposition from the public at large. But there have been moments of great controversy, where presidents seemed to conspire against due process. In hindsight, a few were wise decisions, resulting in the calming of troubled waters. Others incited entirely new hurricanes, and one led to the downfall of an administration. Following are the landmark cases, listed in chronological order, that rank as the most contentious acts of clemency ever offered from the inkwells of the chief magistrates.

1

. PARTICIPANTS IN THE WHISKEY REBELLION (TREASON)

PRESIDENT: GEORGE WASHINGTON

CLEMENCY: FULL PARDON, JULY 10, 1795

In spite of his vengeful nature, Alexander Hamilton was the most ardent supporter of empowering presidents with the right of clemency. Through his famous defense of the Constitution in the Federalist Papers, Hamilton suggested, “In seasons of insurrection or rebellion, there are often critical moments, when a well-timed offer of pardon to the insurgents or rebels may restore the tranquility of the commonwealth.”

103

To his surprise, Hamilton found himself fighting against an insurrection not seven years later, leading thousands of federalized troops against the W

HISKEY

R

EBELLION

in western Pennsylvania. Commanding in the field as President Washington monitored events from Philadelphia, Hamilton and his columns marched into the dissentious woodlands in the late autumn of 1794. They encountered almost no resistance, save for the ghostly liberty poles standing anonymously along their route, each crowned with blood-red caps, a symbol of revolution.

Impatient to get their work done before winter, officers and scouts began pulling suspects from their homes in the dark of night, detaining them in barns and cellars. Some 150 civilians were questioned at gunpoint. Two were mortally wounded by accident, while others went days without food. Hamilton interrogated several captives personally, and he soon discovered that the ringleaders had long disappeared into the frontier. With no one of consequence in their possession, the army nonetheless attempted to save face by marching scores of “prisoners” eastward to Philadelphia. The journey began in November and lasted five weeks. Several of the detainees were barefoot. One man died of exposure.

104

On Christmas Day, the victorious army paraded their exhausted captives through the City of Brotherly Love. They were met with cheering crowds, ringing church bells, twirling flags, and the president, fully pleased that the rebellion had been tamed.

The ensuing trials dragged on, with no plausible evidence emerging, leaving many of the accused to rot in squalid jails for months. In the end, nearly all were acquitted except for John Mitchell, a small-time farmer, and Philip Wigle, a pauper, both of whom were described as “simple” and were perhaps mentally slow.

105

Mitchell and Wigle were convicted of treason and sentenced to hang, but Washington realized their deaths would only turn harmless men into martyrs for another rebellion. Nine months after their capture, the incarcerated and the rest of their supposed accomplices received “a full, free, and entire pardon” from their president, though none were ever compensated for their suffering.

106

One of the commanding officers in the surge against the Whiskey Rebellion was Gen. Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee, future father of Robert E. Lee.

2

. MEMBERS OF THE CONFEDERACY (TREASON)

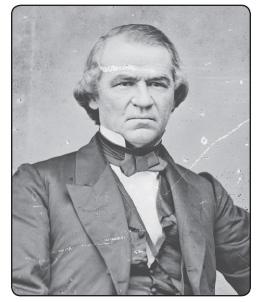

PRESIDENT: ANDREW JOHNSON

CLEMENCY: FULL PARDON AND AMNESTY, DECEMBER 25, 1868

To balance their Union Party ticket for the 1864 presidential elections, Republican officials chose Andrew Johnson of Tennessee over Vice President Hannibal Hamlin of Maine. Along with being pro-Union, Johnson was a southerner and a Democrat, and party leaders figured that the broad appeal of both Lincoln and Johnson all but assured an election victory in November.

The following April, Lincoln was dead, murdered by a Southern Democrat no less. In an attempt to hold on to the presidency, Republicans immediately realized they had made a serious miscalculation in 1864 and would have to wait until 1868 to rectify it.

Andrew Johnson was a steadfast Unionist, but of the old order, insisting on the supremacy of whites in the political arena and supporting states’ rights in local affairs. While Radical Republicans in Congress, such as James Garfield of Ohio, pressed for harsh retributions against the former Confederacy, Johnson supported a more conciliatory approach. In short, he sought to win back the white South by rejecting major changes on race relations.

The president vetoed the extension of the Freedman’s Bureau and a bill on civil rights. He also lobbied against the Fourteenth Amendment, which provided full citizenship to African Americans. His dismissal of Lincoln’s secretary of war, Edwin Stanton, in 1868 only finalized a steadily growing movement to impeach him, a crisis he famously survived by a single senatorial vote. Johnson’s personal train wreck finally ended when his own party refused to nominate him for the 1868 elections.

107

Despite decades of political experience, Andrew Johnson was unable to build common ground between the victorious North and the defeated South.

In a last-ditch effort to heal North-South division, he instead sliced them back open. On Christmas Day 1868, he granted “unconditionally, and without reservation, to all and to every person who directly or indirectly participated in the late resurrection or rebellion, a pardon and amnesty for the offence of treason against the United States.” Only the highest-ranking officials and military officers were excluded. To Johnson, he saw the sweeping gesture as the best way “to secure permanent peace, order, and prosperity throughout the land, and to renew and fully restore confidence and fraternal feeling among the whole people.” The effect was far different than he had hoped. Republicans became convinced that their president was soft on treason, while former leaders of the Confederacy continued to introduce “black codes” that curtailed the newly won civil freedoms of the former slave population.

108

Along with the sweeping amnesty Andrew Johnson gave on Christmas Day in 1868, he also issued 654 individual pardons during his term, more than any other president before him. His successor, U. S. Grant, easily broke that record by allotting 1,332 pardons, mostly to former Confederates.

3

. EUGENE DEBS (SEDITION)

PRESIDENT: WARREN G. HARDING

CLEMENCY: COMMUTATION, DECEMBER 25, 1921

The wiry and righteous Woodrow Wilson took offense of anyone who dared oppose him, while the easygoing Warren G. Harding did not have a rancorous bone in his pudgy, middle-aged body. Their differences reached all the way to the First Amendment, a law Wilson blatantly disregarded after U.S. entry into the Great War when he imposed a slew of congressional acts designed to crush all public opposition to military involvement.

It was under Wilson’s Espionage Act that labor activist Eugene Debs had been arrested. In a public speech in Ohio, Debs had criticized military conscription as undemocratic. He had mentioned the war only once, but it was enough to have him jailed and sentenced to ten years behind bars and have his citizenship revoked for the rest of his life. Even after the war ended, Wilson adamantly refused to show mercy for the sixty-three year-old Debs, whose health was failing inside a federal prison in Atlanta. For as long as he was in office, Wilson promised never to let the man go free, in part because Debs had run against him in 1912 as the candidate of the Socialist Party and slammed the well-to-do Wilson as a tool of big business.

When Harding won the White House in 1920, he saw no reason to continue the incarceration. The accused was a reformer, not a radical, and Debs had already served more than two years. Several labor and religious leaders were petitioning for Debs’s early release, and the president agreed.

Harding initially wanted to issue a pardon on July 4, until the American Legion and other patriotic leagues found out. To them, Debs was still a traitor, undeserving of any compassion. Never one for confrontation, Harding waited until Christmas Day. He invited the federal prisoner to meet him at the White House, unguarded and in private, for an official termination of the “traitor’s” sentence. The pardon was unpopular, especially with the American Legion, the Veterans of Foreign War, and the nationalistic Mrs. Harding. But the president believed the act was a necessary gesture of goodwill toward the working class and a symbolic end to the suppression of free speech in a democratic society.

109

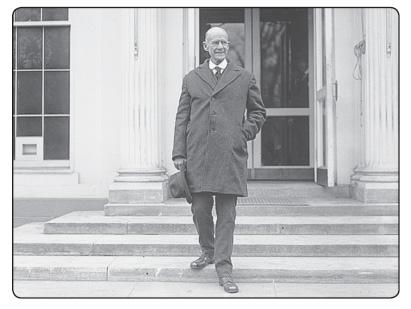

Aging labor leader Eugene V. Debs walks out of the White House shortly after Warren Harding grants him clemency.