History Buff's Guide to the Presidents (33 page)

Read History Buff's Guide to the Presidents Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #United States, #Leaders & Notable People, #Presidents & Heads of State, #U.S. Presidents, #History, #Americas, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Reference, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #Political Science, #History & Theory, #Executive Branch, #Encyclopedias & Subject Guides, #Historical Study, #Federal Government

Claiming the dearth was due to backlog, Clinton accelerated the review process in his last months, often bypassing the pardon attorney’s office in examining cases. Showing questionable tact in his last day as president, the departing Clinton signed 140 separate pardons plus 36 commuted sentences. Many of his fortunate beneficiaries were accused of rather mundane offenses—odometer rollbacks, false tax returns, mail fraud. Several had already served their time, including his half-brother roger clinton for drug possession.

And then there was seedy billionaire Marc Rich. A fugitive living in Switzerland since 1983, his alleged crime was tax evasion—forty-three million dollars’ worth. He also acquired oil from Iran during the Tehran hostage crisis, which he sold at greatly inflated prices illegally to the United States during an oil embargo. Exactly why Clinton felt compelled to grant a full reprieve to a fugitive Jewish émigré from Belgium was not immediately apparent. It was later revealed that the Israeli government insisted that Clinton show leniency toward Rich because the oil trader had donated large amounts of money to Jewish causes. Rich’s former wife was also found to be a major contributor to the Democratic Party.

“Pardongate” would haunt Clinton as yet one more stain on his tumultuous last term. In contrast, Rich was still rich, living in opulence among the elite circles of Europe, and free from any further prosecution for his indiscretions in oil and money.

Charges against Marc Rich were first issued in 1983 by U.S. Attorney Rudi Giuliani. Rich’s counsel in the pardon application process was attorney Lewis “Scooter” Libby.

10

. LEWIS “SCOOTER” LIBBY (OBSTRUCTION OF JUSTICE, PERJURY)

PRESIDENT: GEORGE W. BUSH

CLEMENCY: COMMUTATION, JULY 2, 2007

George H. W. Bush and his eldest son were markedly different presidents: the diplomat and the crusader, the conservative and the spendthrift, the reticent and the recalcitrant. But in one aspect they were in lockstep. Both were absolute misers when it came to forgiving crime, unless it involved someone from within their White House.

In the War on Terror, the George W. Bush administration was adamant about connecting the Saddam Hussein regime with weapons of mass destruction. When evidence did not support their view, they generally ignored or dismissed it, including a report from diplomat Joseph Wilson that refuted a rumor that Iraq had purchased yellow-cake uranium from Niger. Either through miscommunication or by design, Bush nonetheless claimed in his 2003 State of the Union address that Iraq had indeed acquired the pre-nuclear material.

125

Wilson publicly criticized Bush’s miscue (and the administration later admitted it was mistaken). But at least one Bush official, possibly in retaliation against Wilson, leaked the fact that the diplomat’s wife, Valerie Plame, was an undercover CIA operative. Whether or not the disclosure was malevolent, it was nonetheless seen as a major breach of security.

An ensuing investigation indicated that Dick Cheney’s

CHIEF OF STAFF

, Lewis “Scooter” Libby, was one of the possible sources and that Libby had been told of Plame’s covert status by the vice president. During questioning, Libby claimed that he learned of Plame’s role in the CIA through the media and only after the leak had been committed. Both statements were false. For these and other infractions, prosecutors convicted him of perjury and obstruction of justice. Ordered to spend thirty months in prison, he was about to begin serving his time when the president commuted the sentence.

126

Controversial leaks have been part of the executive world since New York was the national capital, and Bush was certainly not the first to grant clemency for a prominent member of the government. But Libby’s case was unique in that he was one of the highest-ranking White House officials ever tried, convicted, and sentenced for a federal crime.

127

When George W. Bush was governor of Texas, he granted the fewest acts of clemency of any governor in that state since the 1940s.

James Garfield once said, “Assassination can no more be guarded against than death by lightning.” He knew from experience how quickly lightning could strike, having lost so many comrades and his president during the Civil War. In the fifteen years after Abraham Lincoln’s death, assassins killed twenty public officials in the United States and seven foreign heads of state. In 1881, Garfield would be next.

128

The Constitution includes no assurances of, or funding for, executive safety. For the first twenty-five presidents, a paltry security detail varied from year to year. For James Monroe, protection consisted of a few civilian guards and a doorkeeper. Congress permitted the often-threatened John Tyler to have four police officers (called “doormen”) at the White House. Franklin Pierce was the first to hire a full-time bodyguard.

Not until 1894 did the Secret Service enter the picture, in extralegal fashion. A division of the Treasury Department, the Secret Service initially investigated counterfeiting, fraud, bootlegging, and other revenue issues. Looking into threats from Colorado gamblers against Grover Cleveland, a few operatives began to watch over the president and his family, extending their assignment at the insistence of the first lady. One war, another assassination, and a score of rejected congressional bills later, the Sundry of Civil Expenses Act of 1906 authorized a portion of the Secret Service to guard “the person of the President” thereafter.

129

Access to the “First Citizen” has lessened ever since, but the assaults have continued. In 1974, unemployed and distraught Samuel Byck tried to hijack a commercial airliner with the intent of crashing it into the White House to kill President Nixon. He instead shot and killed an airport guard, a pilot, and himself. George H. W. Bush’s term witnessed sixteen separate cases of perpetrators jumping the White House fence. During Bill Clinton’s tenure, the Executive Mansion experienced a suicide plane crash on the South Lawn, incoming shots from a 9mm handgun, and a barrage of automatic rifle fire that struck the building’s north facade.

No executive has served without incident. A fourth of them have been personally assaulted, and four have been murdered. Without question, it is a dangerous job. But as the following cases illustrate, the country can be a dangerous place. Following in chronological order are the ten cases that can be classified as direct attacks upon the First Citizen of the country.

130

1

. ANDREW JACKSON (JANUARY 30, 1835)

“I try to live my life as if death might come at any moment,” claimed Andrew Jackson, neglecting to add that death came frequently in his life, only to other people. As an adult, Jackson amassed slaves and was quick to the lash. During his military service, he butchered Creeks, Seminoles, and British soldiers with impunity. In cases of personal disputes, he readily dueled, killing a man on one occasion, but not before his opponent lodged a bullet within an inoperable inch of his vengeful heart.

131

As chief executive, he could be just as authoritarian, threatening to attack South Carolina over a tariff issue, banishing the Cherokee to the Trail of Tears, and bullying congressmen into submission. Not surprisingly, he had received more than five hundred death threats by the middle of his second term. An attack finally came while Jackson was attending memorial services on Capitol Hill for a recently deceased legislator. The president, looking far older than his sixty-seven years, filed out of the Rotunda with the rest of the congregation, when a bearded thirty-year-old male approached him, raised a pistol, and fired.

132

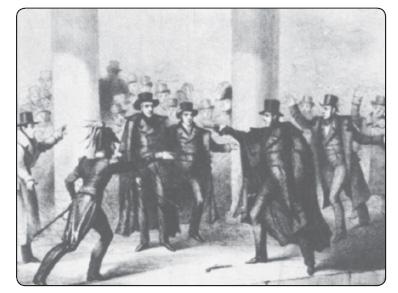

Mentally unwell Richard Lawrence attempted to kill Andrew Jackson at the Capitol. Onlookers, including Davy Crockett, rushed to subdue the president’s assailant.

The percussion cap detonated with a staccato clap, but the gun did not go off. Stepping still closer, the assailant fired another pistol, and again the weapon failed. True to his militant nature, Jackson charged the man, ready to strike. Onlookers, including Tennessee Congressman Davy Crockett, violently piled on the would-be assassin.

The shooter turned out to be an English émigré named Richard Lawrence, an unemployed house painter. When questioned, Lawrence insisted that Jackson had killed his father three years before, when in fact his father died in England twelve years previous. Suspicions of his mental health were confirmed when Lawrence also claimed to be the rightful heir to the throne of England.

133

Conspiracy theories germinated quickly. Jackson accused militant southerner John C. Calhoun, his former vice president. Calhoun denied the accusation and called Jackson a dictator. Others wondered if the entire assassination attempt had been staged to boost the president’s status. Regardless, the death threats continued unabated. Six months after the attempted shooting, an unknown individual, who signed his name “Junius Brutus Booth,” assured the president, “I will cut your throat whilst you are sleeping.”

134

Richard Lawrence was found not guilty by reason of insanity. He was eventually committed to an asylum in Washington. The building was later named St. Elizabeth’s Hospital and housed another would-be assassin, John Hinckley Jr.

2

. ABRAHAM LINCOLN (APRIL 14, 1865)

Mary Todd Lincoln had reason to believe she and her husband were surrounded by enemies. They were. During the course of a four-year war, Washington had swelled from forty thousand people to one hundred thousand, nearly a third of whom were refugees from the battered South. But the danger seemed to have passed with the surrender of the Confederacy’s largest army at Appomattox Court House. Later that week, on Good Friday, Mary and her husband attended their favorite playhouse, an establishment they had frequented many times before. In light of the warm occasion, invitations were personally extended to Lt. Gen. U. S. and Julia Grant, to chief of the War Department telegraph office Thomas Eckert, to House Speaker Schuyler Colfax—all of whom declined. Mary then asked Clara Harris, the daughter of a New York senator. She accepted and brought along her fiancée, Maj. Henry Rathbone.

135

Midway through the play, a dark plot would come to fruition. For months a cadre of Confederate sympathizers had planned to kill the Union heads of state, and the ringleader took it upon himself to remove the chief executive. Slipping into the balcony box, with its four silhouetted occupants, the perpetrator leveled a single-shot derringer at the president’s occipital lobe and sent a .44-caliber ball into his brain. Startled by the noise, Mary Todd Lincoln turned to see her husband’s head droop forward. A waif of gunpowder entered her nostrils as a knife-wielding man bullied his way between her and her husband. Rathbone attempted to stop the assailant, only to have his arm slashed wide open. The man leaped to the stage and escaped through a backstage door as confusion, then mass terror, swept through the crowded theater.