History Buff's Guide to the Presidents (27 page)

Read History Buff's Guide to the Presidents Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #United States, #Leaders & Notable People, #Presidents & Heads of State, #U.S. Presidents, #History, #Americas, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Reference, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #Political Science, #History & Theory, #Executive Branch, #Encyclopedias & Subject Guides, #Historical Study, #Federal Government

Among these was “an act granting a pension to John Hunter.” The subject claimed permanent disability from “May, 1864, [when] he received a gunshot wound in the right leg while in a skirmish.” Cleveland found no army record of the injury, but the man had indeed hurt his leg—fifteen years after the war—while picking dandelions. In another case, Senate Bill 363 was to reward Edward Ayers, who claimed his hip had been permanently damaged from shellfire in the battle of Days Gap, Alabama. The president passed on the idea, considering that Ayers had deserted his unit shortly after the battle.

Not surprisingly, veterans took offense at Cleveland’s zealous scrutiny. In the 1888 elections, critics also noted that he had hired a substitute in the Civil War, whereas his opponent, Republican Benjamin Harrison, reached the rank of general in the Union army. Harrison won the old soldier vote and the election.

48

Harrison, in deference to his support base, signed the Dependent Pension Act of 1890 (which Cleveland had vetoed in 1887), granting monthly stipends to all honorably discharged Union veterans, their widows, and their children. Soon after, the U.S. Treasury went from a one-hundred-million-dollar surplus to a huge deficit. Shocked pundits soon realized that the new pension program would eventually cost far more than the Civil War itself.

To stop the bleeding, the nation returned Cleveland to the White House in 1892. For his comeback inaugural address, “Old Veto” was gracious but direct. The country was in trouble, he said, because it was guilty of “wild and reckless pension expenditure, which overleaps the bounds of grateful recognition…and prostitutes to vicious uses the people’s prompt and generous impulse.” His second term brought forth a scything of 170 more bills.

49

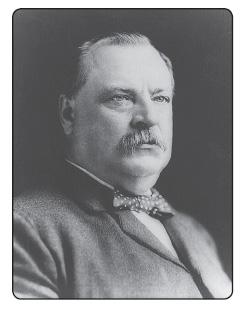

To prevent a few thousand goldbricking Union veterans from sapping the national treasury, Grover Cleveland conspicuously vetoed hundreds of dubious pension applications. His diligence offended thousands of old Union soldiers, who subsequently voted en masse against him in the 1888 elections.

Average number of vetoes per president before Cleveland: 9.6

Average number of vetoes per president after Cleveland: 90.1

3

. HARRY S. TRUMAN (250)

REGULAR VETO: 180

POCKET VETO: 70

OVERRIDDEN: 12

Republican Arthur Vandenberg described Friday the Thirteenth as his lucky day. A fellow senator had just become president: “Truman came back to the Senate this noon to have lunch with a few of us…It means that the days of executive contempt are ended; that we are returning to a government in which Congress will take its rightful place.”

50

The following Monday, Truman gave his first address to a joint session of Congress. Millions listened via live radio, as Vandenberg and company interrupted Harry with seventeen rounds of thunderous applause. Across the nation, Truman’s approval ratings topped 80 percent. Three weeks later, the Third Reich collapsed. Later that summer, the Japanese Empire surrendered, two years sooner than expected.

51

But after the burst of celebration came the recoil. The country was up to its flagpoles in debt. The job market became flooded with returning soldiers. Military factories closed. Employment spawned ugly labor strikes. In the 1946 midterms, Vandenberg and the Republicans turned on their old colleague and won majorities in both Houses. A war of vetoes ensued.

Congress churned out a string of tax cuts favoring the upper class. Truman accused them of pandering to the rich and vetoed them all. Capitol Hill answered with a series of overrides. In 1947, Congress passed the Taft-Hartley Act, virtually neutering organized labor. Truman vetoed that as well. They overrode him again, leading Truman to call the Eightieth Congress “good for nothing” and the “worst ever.”

52

Though he often lost, Harry started to look like the underdog, an image that paid huge dividends in the 1948 presidential race. Not only did he score a miracle win over dashing Thomas Dewey, but his party also regained the House and Senate.

His joy was short-lived, though. The following year, the United States lost its nuclear monopoly to the Soviets. Then came the “loss” of China, sparking a nationwide Red Scare and a fight over the definition of liberty itself. First came the Internal Security Act, requiring communists and their “sympathizers” to register with the Justice Department. It also empowered the government to forcibly detain anyone suspected of being a subversive. The bill was, in Truman’s eyes, “even more un-American than communism.” He refused to sign it. Congress answered with a crushing override.

53

War in Korea only deepened the crisis, leading to a resurgence of the witch-hunting Committee on Un-American Activities in the House and the rise of Joe McCarthy in the Senate. Pandering to the fearmongers, Congress passed the Immigration and Nationality Act, denying all former communists entry into the country, including those who had fought against the Third Reich. For Truman, fighting reds in Asia was one thing, but turning on old allies was inexcusable. He vetoed the act in no uncertain terms. Congress rejected him yet again, and the measure became law.

54

Though federal courts eventually struck down much of the 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act as unconstitutional, portions involving detainment or deportation of people based on their political views were reinstated through the Patriot Act of 2001.

4

. DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER (181)

REGULAR VETO: 73

POCKET VETO: 108

OVERRIDDEN: 2

In the rich lexicon of American slogans, “I like Ike” may be the most plainly insightful because Dwight Eisenhower rarely inspired primal emotion. The very reason for his meteoric rise in the blood sports of war and politics was his freakish ability to suppress passion—his and everyone else’s.

So went his vetoes. Most were private relief initiatives, quietly pocketed or returned to the appropriate house with a sensible note. A handful involved the minting of commemorative coins—fifty-cent pieces for the tercentennial of Northampton, Massachusetts, for example. In 1958, he politely denied the Coast Guard sixty million dollars for the development of a nuclear-powered icebreaker.

He was only overturned twice, and they both came late in his second term. The first rebuff involved the Tennessee Valley Authority, the flagship of the New Deal. Ike wanted to privatize it; Congress moved to keep it afloat on government money. Then came the last regular veto of Eisenhower’s presidency, a pay hike to federal employees. He thought it was inflationary, and legislators declared it was overdue.

Vetoing S1901(1959), a bill that heavily subsidized the tobacco industry, might have brought mixed feelings for Eisenhower. Ten years previous, Ike had to give up smoking cold turkey because his physician expressed concern over his four-pack-a-day habit.

5

. ULYSSES S. GRANT (93)

REGULAR VETO: 45

POCKET VETO: 48

OVERRIDDEN: 4

Within the first minute of his first inaugural address, U. S. Grant made his intentions abundantly clear: “On all leading questions agitating the public mind I will always express my views…and when I think it advisable will exercise the constitutional privilege of interposing a veto to defeat measures which I oppose.” Grant kept his word, rebuffing more bills than the previous seventeen presidents put together. He was also the first to rely heavily on the pocket veto, again producing more than anyone before.

Most vetoes involved private relief funds, including compensations for property destroyed during the Civil War. Congress allotted twenty-five thousand dollars, for example, to one Paducah, Kentucky, homestead torn down in battle (at a time when large farmhouses cost six thousand dollars). Grant blocked it. Another involved awarding East Tennessee University several thousand dollars in war-related damages to its campus. In vetoing the university’s claims, Grant expressed sympathy, but he said loss was part of war, and if he signed the bills, he warned “the ends of the demands upon the public Treasury cannot be forecast.”

55

Relatively weak when it came to protecting the civil rights of blacks and Native Americans, Grant took a hard line against soft money and heavy federal spending, using his veto power early and often against a spendthrift Congress.

Grant’s most famous veto involved money. When the Panic of 1873 triggered a global depression, bankrupt businessmen and indebted farmers called for an increase in the public supply of greenbacks. Congress agreed. The resulting “Inflation Bill” of 1874 ordered a release of one hundred million dollars into the economy to boost the money supply by roughly 25 percent. Grant initially supported the idea, then he changed his mind.

The president, who had been flat broke many times in his own life, argued that the only way to regain financial stability was to return to the gold standard, however painful the journey might be. The impoverished public lashed out against him, but major investors applauded his “hard money” courage. Conservative media went so far as to call him a hero, and the

London Post

equated Grant’s veto of the Inflation Bill with his triumph at Vicksburg. True to his prediction, the depression ended, but like the Civil War, it took four long years to transpire.

56

U. S. Grant was the first of a dozen presidents to officially request a line-item veto. Only William Jefferson Clinton would get the privilege, striking eighty-two items from eleven bills before the Supreme Court declared the practice unconstitutional.

6

. TEDDY ROOSEVELT (82)

REGULAR VETO: 42

POCKET VETO: 40

OVERRIDDEN: 1

Like his cousin to follow, this Roosevelt never saw an opposition legislature, and he reveled in being the president. As many noted, the insatiable TR aimed to be “the bride at every wedding and the corpse at every funeral.”

But “government by veto” repulsed him. “I have a right to veto every bill,” he told a senator in 1905. But he added: “If we do not manage to work together on these matters it will be a bad thing for the country…This system is postulated on self-restraint.”

57

True to form, Roosevelt was careful on what he vetoed. Most, like Grant’s and Cleveland’s, involved private pensions. Others blocked favorable treatment of large corporations. Some bills he may have rejected for being utterly mundane, such as

To refund certain tonnage taxes and light duties levied on the steamship Montara without register

; or the tremendously banal

Granting to the city of Durango, in the State of Colorado, certain lands therein described for water reservoirs

; or the strangely appropriate,

To amend an act for the prevention of smoke in the District of Columbia

.

His only defeat came in May 1908, when he refused a deadline extension for construction of a dam along the Minnesota-Canada border. The fiscally conservative Roosevelt argued that the American public should not have to pay more simply because the Rainy River Construction Company could not get a job done on time. The House sympathized with the company, which had struggled during a recent recession. The extension passed with a 240–5 vote in the House and a unanimous 49–0 in the Senate.

58