History Buff's Guide to the Presidents (18 page)

Read History Buff's Guide to the Presidents Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #United States, #Leaders & Notable People, #Presidents & Heads of State, #U.S. Presidents, #History, #Americas, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Reference, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #Political Science, #History & Theory, #Executive Branch, #Encyclopedias & Subject Guides, #Historical Study, #Federal Government

1

. 1789

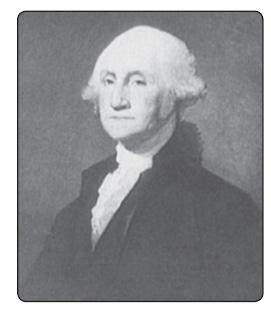

| GEORGE WASHINGTON | 69 | (100% OF FIRST-CHOICE VOTES) |

| JOHN ADAMS | 34 | (49% OF SECOND-CHOICE VOTES) |

Thinking of a particular general from Virginia, Benjamin Franklin surmised: “The first man put at the helm will be a good one. Nobody knows what sort may come afterwards.”

26

Realistically, only two names were respected enough to be given the executive chair, and the good doctor from Philadelphia was one of them. Yet by 1789, he suffered from persistent kidney stones, memory loss, and the knowledge that his eighty-two-year-old body was far beyond its life expectancy. “I am grown so old and feeble in mind, as well as body,” Franklin confessed to a friend, “that I cannot place any confidence in my own judgment.”

27

The alternative was thus a virtual automatic. At age fifty-six, George Washington was old enough to be venerable and young enough to survive at least one term. Better still, he hailed from the Old Dominion, the most populous state, resting comfortably between the commercial North and the agrarian South. Most important, he had been commander in chief during the Revolution and president of the Constitutional Convention (both positions he attained by unanimous election). Undoubtedly the only true roadblock to Washington’s appointment was the man himself.

Citing “growing infirmities of age,” he wrote to fellow veteran Charles Pettit, “I have no wish, which aspires beyond the humble and happy lot of living and dying a private citizen on my own farm.” To Benjamin Lincoln, his second-in-command at Yorktown and a leading supporter of his appointment, Washington pleaded, “I most heartily wish the choice to which you allude may not fall upon me.”

28

The man who did not want to be either king or president felt compelled to serve when he was elected to the office unanimously.

Some historians question whether he protested too much, feigning humility while assuming the prize was his. But he had good reason to believe his remaining days were few. His father died at forty-nine, and his paternal grandfather died at thirty-six. Of Washington’s nine siblings, seven were deceased. Washington himself was nearly blind, growing deaf, with one solitary tooth left in his aching jaw. After the Revolution, the general informed his dear Marquis de Lafayette that he “might soon expect to be entombed in the dreary mansions of my father’s…but I will not repine—I have had my day.” His day would be extended by a unanimous vote. With no primaries, conventions, or viable challengers, all sixty-nine electors voted for Washington.

29

As stipulated by the selection process, the runner-up became vice president. Washington expected Massachusetts, birthplace and bank vault of the Revolution, to produce a favorite. One New Englander, whom he marginally knew, caught his attention as brash but particularly intelligent. “From different channels of information,” Washington wrote from Mount Vernon, “Mr. John Adams would be chosen Vice President. He will doubtless make a very good one.”

30

Of the thirteen original states, only ten took part in the 1789 election. Rhode Island and North Carolina had not yet ratified the Constitution, and the New York House and Senate disagreed on specific electors and cast no vote.

2

. 1792

| GEORGE WASHINGTON | 132 | (100% OF FIRST-CHOICE VOTES) |

| JOHN ADAMS | 77 | (58% OF SECOND-CHOICE VOTES) |

Before embarking on his first term, Washington said to Henry Knox, “My movements to the chair of Government will be accompanied by feelings not unlike those of a culprit who is going to the place of his execution.”

31

Life as president confirmed his trepidations. Though it began with fireworks and accolades, his administration soon fractured from infighting, particularly between his idealistic secretary of state, Thomas Jefferson, and his elitist treasury secretary, Alexander Hamilton. Unresolved problems with Britain, including redcoat garrisons on the frontier and the Royal Navy threatening American seafarers, left the lifespan of his country in doubt.

Washington also found himself the frequent target of a free press. Principle among his accusers were the

National Gazette

, a Republican-Democrat paper tangentially connected to Jefferson, and the

Philadelphia General Advertiser

, run by Benjamin Franklin’s grandson. Reading accounts of his supposed desire for monarchy, misquotes and forgeries bearing his name, and column titles such as “The Funeral of George W—n,” he openly feared a disintegration of public support, insisting: “These articles tend to produce a separation of the Union, the most dreadful of calamities.”

32

Adding to his pains were the reminders of his own mortality. For his innumerable ailments he took laudanum, a tincture of alcohol and opium. Early in his first term, a sizable tumor grew from his left thigh, requiring an invasive and painful operation. As old comrades died one by one, a bout of flu nearly killed him in the spring of 1790.

33

In spite of his condition, and because of the failing health of his country, the man reluctantly accepted the possibility of what he dejectedly called “another tour of duty.” Once again, Washington was every elector’s first choice for president. He returned to the helm with the hope of retiring midterm. Within months of his second inauguration, he confided in a letter to James Madison his overwhelming desire to leave politics for Mount Vernon, “to spend the remainder of my days (which I can not expect will be many) in ease and tranquility.” His wish to step down went unfulfilled, and he served his second term. Sadly for Washington, his lengthy public service took its toll, and he lived less than three years after his presidency was over.

34

Despite refusing to run for a third term, George Washington still received two electoral votes in the election of 1796.

3

. 1820

| JAMES MONROE (D-R) | 231 |

| JOHN QUINCY ADAMS (D-R) | 1 |

In April 1820, Maryland Representative Samuel Smith called his fellow. Democratic-Republicans to gather in Congress for a presidential caucus. Barely forty legislators bothered to attend, and they immediately disbanded for lack of quorum. By default, the sixty-year-old pragmatic President James Monroe was nominated for reelection.

35

So went the dubiously titled “Era of Good Feelings,” when one party thoroughly dominated affairs. Absent was any heir of the old guard Federalists. Monroe’s congenial and diplomatic style did much to prevent the rise of a new opposition party or a new war with Britain. The Compromise of 1820 added Missouri and Maine to the Union, maintaining Senate parity between slave and free states. Only the Panic of 1819 remained unsolved, as bank failures sent the country into its first true economic depression. Yet the dispossessed—urban laborers and frontier farmers—remained outside the political sphere, and Monroe ran almost unopposed.

For years the legend persisted that a rogue ballot was cast to maintain George Washington’s record as the only unanimously elected president. Yet electors submitted their choices at different locations and dates, and they were generally unaware of how others were voting. The lone ballot for John Quincy Adams, unsolicited at that, came from New Hampshire’s William Plumer. It turned out that the elector wasn’t concerned about Washington’s legacy. Plumer sincerely disliked Monroe, whom he said had “not that weight of character which his office requires.”

36

Regardless, indifference beset the general public, prompting the

Ohio Monitor

to warn: “In most of the States the elections occur with great quietness, too great, perhaps, for the general safety of the Republic.” Certainly anyone outside the privileged circles of the Old Dominion had cause for concern. Of the first ten executive terms in the nation’s history, Monroe’s reelection made it nine terms and counting for Virginia.

James Monroe could possibly have won by a larger electoral margin. Out of 235 electoral votes, only 232 were cast because electors from Mississippi, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee died before they could submit their selection.

4

. 1936

| FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT (D) | 523 |

| ALFRED LANDON (R) | 8 |

Republican Governor Alfred Moosman Landon of Kansas embodied the median. Average in height and build, middle-aged “Alf” was a moderate in word and deed. He made his money in industry, oil in particular, mostly through the engagement of a solid work ethic. An uninspiring speaker with a modest intellect, Landon, however, held one unique characteristic—he was the only Republican governor to win reelection in 1932.

Essentially a sacrificial lamb, Landon faced the mammoth alliance of FDR and the New Deal. A tacit progressive, the Kansan personally supported the New Deal, yet he argued that the inherently inefficient colossus could be better managed at the state level. He also warned against the climbing national debt and the “extraordinary powers” exercised by the incumbent. Much to his demise, he openly criticized Social Security, FDR’s most popular new program. In contrast, Roosevelt played Robin Hood, bashing big corporations, opulent securities, and major banks, consequently winning over the less privileged majority.

37

In 1936, FDR was coolly confident that he could defeat Alf Landon in the November election. The result was more like a severe beating, a landslide greater than Roosevelt ever envisioned.

Roosevelt Library

By November, the Civilian Conservation Corps and the Emergency Relief Appropriations Act were employing millions. Joblessness went down, grain prices slowly went up, and the repeal of Prohibition allowed spirits to legally flow again. Roosevelt calculated he would get 360 electoral votes and Landon 171. The polls of Gallup and Roper predicted a wider sum, estimating the president would carry every state but three.

38

Election Night saw an astounding 83 percent voter turnout. Sequestered in his private study at Hyde Park, FDR listened to the early returns. Within an hour he emerged to celebrate with family and friends, his countenance beaming from the beating he was giving the GOP.

In the end FDR collected nearly 28 million votes to Landon’s 16.7 million. The Democrats took 331 of 435 House seats and 76 of 96 chairs in the Senate. All forty-eight states, save Maine and Vermont, went to Roosevelt, giving him the widest margin of victory of his presidential career and the most lopsided electoral vote in the era of universal suffrage.

39

Among those who endorsed Alf Landon in the 1936 campaign were media giant William Randolph Hearst and track star Jesse Owens.

5

. 1984

| RONALD REAGAN (R) | 525 |

| WALTER MONDALE (D) | 13 |

On paper the former vice president had a chance. A 1983 Gallup Poll revealed that 44 percent of Americans considered themselves Democrats, and only 25 percent sided with the GOP. Reagan’s soaring military expenditures and reduced taxes pushed yearly deficits to $200 billion, while social and educational programs were consistently reduced or eliminated. Divisions between moderate and conservative Republicans threatened to split the party, and Reagan continued a habit of embarrassing miscues. One such remark summoned international condemnation. During a radio sound check months before the election, the president jested, “I am pleased to tell you I just signed legislation which outlaws Russia forever. The bombing begins in five minutes.”

40