History Buff's Guide to the Presidents (19 page)

Read History Buff's Guide to the Presidents Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #United States, #Leaders & Notable People, #Presidents & Heads of State, #U.S. Presidents, #History, #Americas, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Reference, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #Political Science, #History & Theory, #Executive Branch, #Encyclopedias & Subject Guides, #Historical Study, #Federal Government

Diluting Reagan’s minuses was an apparent recovery from a lengthy recession, one that had reached its depth during Mondale’s vice-presidential years in the White House. Primed in part by renewed defense spending, unemployment steadily declined, the Federal Reserve Board lowered prime lending rates below 10 percent, and the Gross National Product rose to an annual rate of an exceptional 7.6 percent.

41

Yet statistics mattered little in a campaign based on sentiment. Both candidates inundated voters with primal themes of patriotism, family, and morality. In this contest, Reagan was clearly the superior. Naturally warm and optimistic, his indissoluble confidence bonded well with voters, whereas Mondale’s serious countenance and stiff demeanor exhumed memories of Jimmy Carter’s dark delivery style. Mondale’s selection of a female running mate, a first for a major party, also failed to produce widespread support. New York’s Geraldine Ferraro did invoke a reaction, however, especially among evangelicals and conservative Roman Catholics, who disdained her lenient stance on abortion.

42

On November 6, all polls pointed to a Republican victory. Only the margin remained in doubt, and some observers openly wondered if Reagan would win all fifty states. Early returns were not close. The incumbent won states by 20 percent and more. By 8:00 p.m. eastern time, barely into the Election Night broadcast, CBS announced Reagan as the victor. Within thirty minutes, ABC and NBC followed suit, despite the fact that polls were still open in nearly half the states. Though abrupt, the predictions proved accurate. When all was counted, Mondale only managed to take his home base of Minnesota plus the District of Columbia.

43

Even Ronald Reagan was surprised at the overwhelming support he received when he accepted the renomination of his party in 1984.

The Democrats were not breaking new ground in selecting Geraldine Ferraro in 1984. The first woman to run for an executive position was New York’s Victoria Woodhull, who received the People’s Party nomination for president in 1872. Twenty-six women in various small parties followed in her footsteps until Ferraro’s more famous attempt.

6

. 1972

| RICHARD M. NIXON (R) | 520 |

| GEORGE MCGOVERN (D) | 17 |

Robert Kennedy once referred to George McGovern as “the most decent man in the Senate.” A decorated veteran of World War II, a history PhD, supportive of the impoverished and elderly, he was bitterly opposed to the war in Vietnam and was running against a political machine that had recently conducted the W

ATERGATE

breakin.

44

Though overtly liberal, McGovern benefited from a radical shift in the Democratic nomination process, one he personally championed. Traditionally, party leaders dominated the selection of presidential candidates. By 1972, caucuses and primaries became the forums for nomination, largely turning national conventions into rubber stamps and morale boosters.

If the new method “democratized” nominations, it also alienated the party elite. Exemplifying McGovern’s weakened position, he only managed to raise half as much money as Nixon (thirty million dollars to sixty million dollars), and he struggled to find a running mate.

45

Rejection followed rejection, until Missouri Senator Robert Eagleton accepted the offer. Weeks later, information surfaced that Eagleton had suffered bouts of depression, was currently on medication, and had received two rounds of electroshock therapy in the 1960s. McGovern initially vowed to support him “1,000 percent,” then dropped him from the ticket.

46

The embarrassed candidate weathered yet another series of public failures to find a deputy, until Sargent Shriver of Maryland accepted. The energetic Shriver was a noble choice. Though best known as an in-law to the Kennedys, Shriver was a cofounder of the Peace Corps, Head Start, Job Corps, and the Special Olympics.

Regardless, McGovern’s popularity dropped from the fortieth percentile to the twenties, while Nixon’s climbed. Successfully distancing himself from the slow-moving W

ATERGATE

investigation, bumped by publicity in the August Republican Convention, and aided by Henry Kissinger’s late October statement that “peace is at hand” in Southeast Asia, Nixon went into November leading the polls by two-to-one margins.

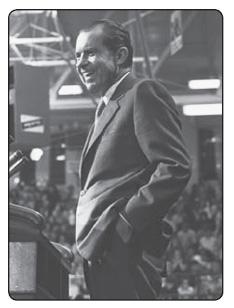

Voters flocked to Nixon in 1972 because of his political strength and personal integrity. Within a year, public perceptions of the stoic Nixon changed considerably.

Nixon Library

In the final popular vote, Nixon took forty-seven million to McGovern’s twenty-nine million. Not surprisingly, the incumbent won 94 percent of registered Republicans, yet he also garnered nearly 70 percent of moderates, 61 percent of blue-collar workers, and 42 percent of Democrats. McGovern even lost his home state of South Dakota, taking only Massachusetts and the District of Columbia.

47

The 1972 election marked the initiation of the Twenty-Sixth Amendment, which granted eighteen-to twenty-one-year-olds the right to vote in national elections. The majority of them declined the privilege.

7

. 1804

| THOMAS JEFFERSON (D-R) | 162 |

| CHARLES C. PINCKNEY (F) | 14 |

Having narrowly won in 1800 through a contest marred by scathing antagonisms right and left, Thomas Jefferson attempted to calm the warring parties at the outset of his presidency. In his inaugural address, he reminded his countrymen, “Every difference of opinion is not a difference of principle…We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists. If there be any among us who would wish to dissolve this Union or to change its republican form, let them stand undisturbed as monuments of the safety with which error of opinion may be tolerated.”

Though tolerance remained elusive in a country still struggling with the right to dissent, prosperity all but assured reelection for Jefferson. His first term marked years of relative peace. The navy and army were reduced by more than half. The surprise Louisiana Purchase doubled the size of the nation. Taxes on whiskey were repealed.

48

In opposition stood Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, a South Carolina–born and Oxford-educated lawyer, a planter, and a former aide to George Washington during the Revolution. Running with him was Rufus King, a Harvard-primed veteran of the Continental Congress and the Constitutional Convention and a minister to Britain. Despite their credentials, their fellow Federalists neglected to explicitly endorse them.

49

In contrast, Democratic-Republicans were far better organized, staging parades of local officials and militia, penning radiant articles in the

National Intelligencer

and other pro-Jefferson papers, and dumping the scheming Vice President Aaron Burr for the first governor of New York and a longtime Washington confidant, George Clinton.

Reflecting the democratization of the country, only six states chose electors through their legislatures, while eleven opted for general male suffrage. The result overpowered the exclusive Federalist clique, and Jefferson won all but Connecticut, Delaware, and Maryland. Afterward, Jefferson wrote to a friend in France, expressing hope that the decisive outcome signaled the end of political parties, observing that “the two parties which prevailed with so much violence…are almost wholly melted into one.”

50

Of all the states, New Jersey was most friendly to Jefferson, voting in favor of the president 13,039 to 19.

8

. 1864

| ABRAHAM LINCOLN (NU) | 212 |

| GEORGE B. MCCLELLAN (D) | 21 |

“Seldom in history,” wrote Ralph Waldo Emerson, “was so much seated on a popular vote.” Barely four score and seven years old, the United States looked to be on its deathbed. A third of its states were in rebellion. Federal coffers were nearly empty. Suspension of the writ of habeas corpus cast a tyrannical hue upon the White House, while the total number of dead in the war was approaching a half-million.

51

Abraham Lincoln was somewhat surprised in June 1864 to learn that his Republican Party had endorsed him for reelection. His solace soon died with the chilling news from Virginia that U. S. Grant had launched a massive frontal assault upon heavy Confederate defenses at Cold Harbor and lost seven thousand men in twenty minutes. With no foreseeable end to the bloodletting, the president issued a sullen memorandum to his cabinet in August: “This morning, as for some days past, it seems exceedingly probable that this Administration will not be reelected.”

52

Poised to replace him was the handsome, confident, former commander of the Army of the Potomac, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan. The Democratic Convention announced its selection of “Little Mac” from the echoing Wigwam in Chicago, the very hall in which Lincoln was nominated four years previous.

Scurrying to fashion wider support, Lincoln ran under the banner of the “National Union Party,” a compendium of loyal Republicans and war Democrats. For vice president, party officials dumped Maine abolitionist Hannibal Hamlin for Tennessee’s military governor, Democrat Andrew Johnson. The government also provided a service for the first time in American history—absentee voting for soldiers.

Fortunately for Lincoln, McClellan continued his old military habits and failed to act boldly. He allowed the Democrats to pair him with an antiwar plank and George H. Pendleton of Ohio, both of which endorsed a permanent division of the Union. Refusing to label the war a failure and thus disgrace the work of his former troops, McClellan consequently alienated his own party. Meanwhile, the Union army achieved a surprising run of successes. In September, Atlanta fell, as did coastal areas of Alabama and North Carolina. Days before the election, Gen. Philip H. Sheridan scored a dramatic victory in the Shenandoah, securing the whole of the valley for the North.

53

Still, as Lincoln watched soldiers vote on the White House lawn, he was unsure. He was likely to lose the Border States. New York and Pennsylvania, which accounted for half the electoral votes needed for victory, were too close to call.

For the first time in U.S. history, soldiers in the field voted in a presidential election. Overwhelming troop support for Lincoln and the National Union coalition, especially among troops in the eastern theater, turned the 1864 election into a rout.