His Name Is Ron (25 page)

Authors: Kim Goldman

Kim worried about whether or not the jury was getting it, but she noticed that Juror 6 seemed very interested in the testimony. He leaned forward in his chair, writing copious notes. Dominick Dunne noted the change in him as well, and offered the opinion that he thought the man was upset and disappointed that it was being proved to him that the “killer” had actually done it.

Another DNA expert followed Dr. Cotton to the stand and, over the course of several days, added more incontrovertible evidence. Gary Sims, a veteran analyst at the California State Department of Justice laboratory in Berkeley, testified that the DNA in four bloodstains on the glove found

behind the guest house on the killer's property matched that of either Ron or Nicole. Prosecutors said that at least one stain on the same glove was consistent with the defendant's blood.

Various blood samples collected from inside the defendant's Ford Bronco matched the DNA patterns of the killer, Ron, and Nicole.

Patti and Kim were astonished. Here was the “trail of blood” that led from the crime scene, to the Bronco, to the killer's home, and even into his bedroom. Had there been any shadow of a doubt, it was now permanently washed away. The man sitting at the defense table was indeed the killer who murdered Ron and Nicole.

Kim sat in the front row, weeping silently. The killer stared straight ahead, occasionally whispering to his lawyers. He did not seem to be paying attention to the testimony. Kim wanted to ask: Are we boring you?

Repeatedly leaping out of his chair like some kind of mopheaded jack-in-the-box, Barry Scheck hammered away, using a mixed bag of accusations: He accused police of sloppy procedures; implied that one lab incorrectly interpreted the statistical significance of DNA matches; inferred that police had sprinkled the socks with blood after the fact.

Later Assistant D.A. Lisa Kahn, in a welcome bit of logic, pointed out that some of the blood samples were degraded while others were not. This suggested that they had been subjected to different degrees of exposure to the elements. However, if the drops had been planted or tampered with in the lab, they would have degraded at the same rate. “The evidence shows that neither a lone officer nor a cadre of plotters could have accomplished such a frame-up,” she concluded.

Wrapping up his questioning of Sims, Assistant D.A. Rockne Harmon moved to counter Scheck's suggestion that the samples were “cross-contaminated.” His voice heavy with sarcasm, Rockne asked, “Can DNA fly?”

“I don't think so,” Sims responded, laughing agreeably.

“I mean, there are no scientific studies that have shown that, are there?”

“No. I don't think it has wings.”

There was simply no way to deny the dramatic impact of the DNA evidence, so the defense returned to its conspiracy theme. In Scheck's fantasy world, he saw the investigators trading hair and fiber samples and splashing blood about in a grand, felonious conspiracy.

There were apparently no limits to the fertile imaginations of Scheck and his compadres on the “Scheme Team.” Way back in September, KNBC-Channel 4 had reported that DNA tests of the defendant's socks had revealed the presence of Nicole's blood. Since the tests had not yet been performed,

the report was erroneous. Now that we knew that Nicole's blood was, indeed, on the sock, Scheck found grounds for suspicion. Did KNBC

know

that it was Nicole's blood because they

knew

that detectives had planted it there? Obviously the entire news staff at KNBC had plotted with the police, the D.A.'s office, the coroner, the scientists andâwho knowsâSaddam Hussein?âto frame the wonderful, caring human being who was paying Scheck's enormous fee.

Scheck had built his career on proclaiming the reliability of DNA evidence in order to win the release of prisoners who had been wrongly convicted. Now, as DNA evidence had proved to the entire world who killed Ron and Nicole, here he was, selling his soul in an attempt to convince the jury of the preposterous notion thatâin this caseâthe evidence had been planted.

Patti had never worn the stepmother label. She was always more of a friend than a parental figure to Ron and Kim. But now, as Patti and Kim spent every day together, driving to court, listening to the hours of testimony, and returning home, they developed a closer, more adult-to-adult, friendship. It was one of the positive developments to come out of this horrendous experience.

During the early-morning hours, negotiating the maddening traffic on the freeway, they shared their feelings about everything. Sometimes that meant tears and frustration, other times anger, and sometimes brief moments of levity. Before long, they were finishing each other's sentences and blurting out the same reactions. “We're spending way too much time together,” they joked.

In some respects this was true. Patti checked in by phone with Michael and Lauren several times a day, and tried her best to spend quality time with them. She came to all of Michael's home tennis matches and, whenever possible, drove Lauren to and from special events. But occasionally simmering resentments surfaced and hurt feelings arose.

Michael was the one who tended to turn inward. As far as the trial was concerned, he was optimistic. He thought: This is going great. The DNA evidence was undeniable. You can picture numbers. One in how many billion people? There aren't even that many people on the whole planet. This is cut and dried! You can't argue with these numbers.

But, in fact, Michael also realized that we were living in a complex and crazy world. On one of the few occasions when he was able to come to court, he found himself transfixed by the jury. He was raised not to think in racial

terms, but he now found himself worrying about the large contingent of black faces in the jury box. Can they fly in the face of this incredible evidence? he wondered.

As the days stretched into weeks, and the weeks into months, however, he became saturated. At times, it felt as if the family did not think about or care about or talk about anything other than the trial. Michael was in school from 7:30

A.M

. to 2:30

P.M

. Tennis practice ran from 3:15 until 5:00. Every day, right after tennis practice, he drove to the cemetery to spend a few minutes with Ron. He visited the grave more often than any of the rest of us, keeping his grief private.

But he was a high school junior, an adult-in-the-making. There was a future out there and Michael was busy preparing to face it.

In the evenings at home, when he would try to talk to Patti about something that happened in school, she too often responded with a “Shhh” because she was watching trial coverage or commentary on TV. Michael wanted to shout, “You've been there all day. You've watched the news all night. Enough!” He had other things to tell us and other news to share, but no one had time to listen. By the end of tennis season, he and his doubles partner had amassed a remarkable record of thirty-three victories and only three defeats, but he had difficulty getting us to share his elation. To Michael, it just did not feel like home anymore.

He began to do his homework at his friend Alicia's house. Most evenings, he did not come home until 11:00.

He knew that Patti wanted him around more, and sometimes she grew angry enough to call him, asking him to come home. But they never really talked about it too much. Michael did not want to tell her, or any of us, how he was feeling.

Brian flew to Los Angeles to join us for Memorial Day weekend.

On Saturday we faced a task we had all been avoiding. We knew that it was going to be a wrenching experience and we did not want to do it more than once, so we had waited until the entire family was present. With Brian here, it was time.

It was difficult to believe that nearly a year had passed since we had cleaned out Ron's apartment. At that time, we were unable to do much more than pack his belongings into cardboard boxes and plastic bags. Everything was still stored in our garage.

We spent several hours going through the contents of those boxes, deciding what to do with the tangible remainders of Ron's stolen life. We cried softly throughout the day, and often one of us had to leave the room to regain composure.

Here was a volleyball we had given Ron for his birthday. There were a number of softball bats and, of course, his tennis racquets.

Michael came across Ron's tennis shirt from Oak Park High, which brought back memories of the season when Ron coached his team. “I'm not surprised he kept this shirt,” Michael said. “It was just like him to do that.” He asked if he could keep the shirt in his room.

We found a tie that Ron had worn to Mike Pincus's wedding and decided that it would be nice to give that, along with a red and turquoise pullover, a red jacket, and a bandana, to Mike.

I found the black-and-white houndstooth sport jacket that he wore occasionally, and remembered how incredibly handsome he looked in it.

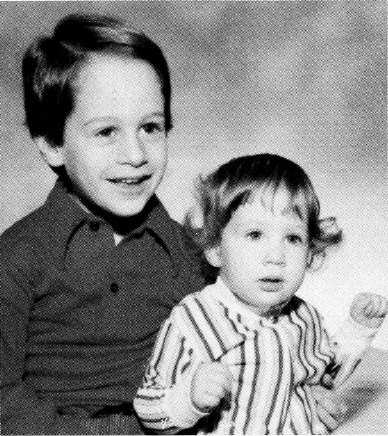

Ron, age three and a half; Kim, age one, in Chicago

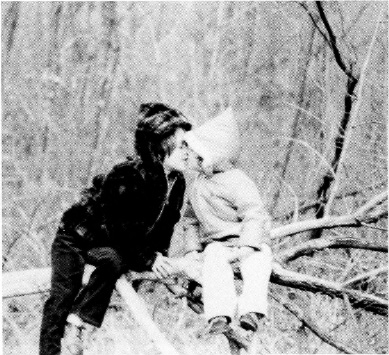

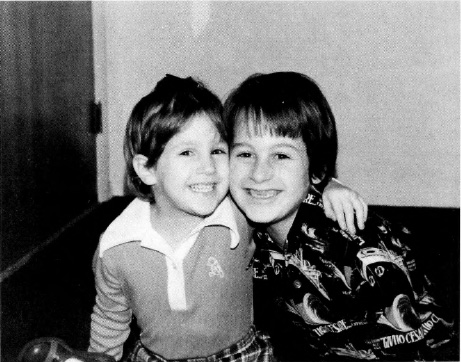

Ron and Kim, 1974

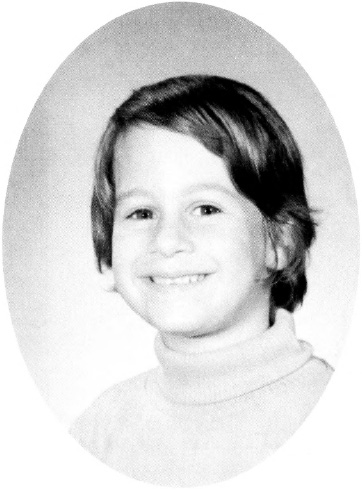

Ron's kindergarten photo

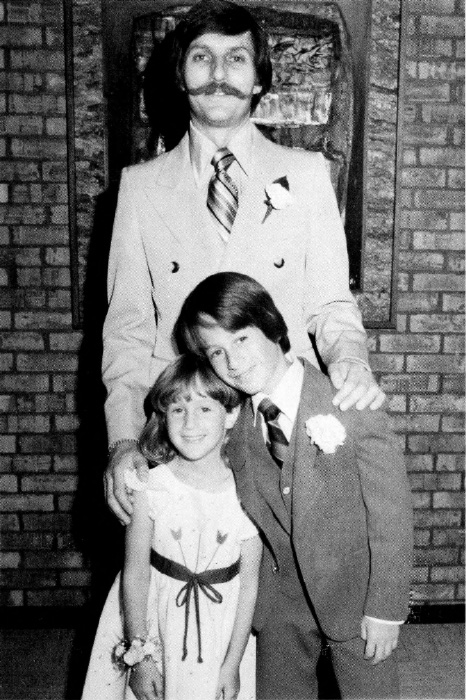

Kim and Ron, December 1975