Heidegger's Glasses: A Novel (2 page)

Read Heidegger's Glasses: A Novel Online

Authors: Thaisa Frank

A few days later Asher Englehardt wrote back in his familiar, hurried script, chiding Heidegger for always acting as though the sensation was new. “There is nothing of substance to depend on, Martin,” he wrote. “All these cups and glasses and whatever else people

have

or

do

are props that shield us from a world that started long before anyone knew what glasses were for and will go on long after there’s no one left to remember them. It’s a strange world, Martin. But we can never fall out of it because we live in it all the time.”

have

or

do

are props that shield us from a world that started long before anyone knew what glasses were for and will go on long after there’s no one left to remember them. It’s a strange world, Martin. But we can never fall out of it because we live in it all the time.”

Asher believed this resolutely and continued to believe it twenty years later when he and his son were taken from their home in Freiburg and deported by cattle car to Auschwitz.

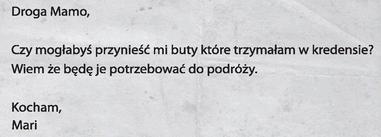

Dear Mother,Can you bring me the shoes I kept in the cupboard? I know I’ll need them for the journey.Love,Mari

THE ORDERS

Nearly a quarter of a century after Heidegger’s revelation about his glasses, a woman with a red silk ribbon snaking around her wrist drove a captured U.S. jeep to a village in Northern Germany. The village was in blackout, and its outpost—a wooden building set far back in a field—would have been easy to miss if she hadn’t made many trips there in the dark. It was a bitter winter night, and snow fell on her face as she walked across the field. She stopped to brush it off and looked at the sky. It was dazzling, brilliant with stars, so wide it seemed carved into separate galaxies. And even at this stage of the war, the woman felt happy. She had just smuggled three children to Switzerland and hoodwinked a guard. Her name was Elie Schacten.

Elie looked at Orion’s hunting dogs and scattered them into points of light—ice-flowers in the dark sky. Then she knocked twice on the shrouded door. It opened, a hand pulled her inside, and an SS officer kissed her on the lips.

What happened? he said. You were supposed to be here yesterday.

There was a problem with the clutch, said Elie. You should be glad I got here now.

I

am

glad, said the officer. But I think you were up to something, my willowy little friend.

am

glad, said the officer. But I think you were up to something, my willowy little friend.

I’m not your willowy little anything, said Elie. She shook him off and looked around. How’s the junk shop? she asked.

You can’t believe what we’re getting, said the officer. Five kilos of Dutch chocolate. French cognac. Statues from an Austrian castle.

They were talking about the outpost—a pine room with crooked beams. It had one oblong window with a blackout curtain and was crammed with objects from raided shops and houses. It was also cold. Wind blew through cracks in the walls, and the coal stove was empty. Elie tightened her scarf and walked through a maze of clocks, books, coats, chifforobes, and two optometrist chairs to a velvet couch. The officer dragged over eight bulging mailbags and leaned in so close Elie felt his breath. She let her hair loose so it screened her face.

That tea-rose is hard to come by these days, said the officer, meaning her perfume. He leaned in closer and touched her blond curls.

Elie smiled and began to read postcards and letters. The sheer amount always overwhelmed her. Most were from Operation Mail—letters written under coercion at camps or ghettos, often moments before the writer was led to a cattle car or gas chamber. Most were on thin, brittle paper and had a dark red stamp that overrode the addresses to relatives. The instructions on the stamp were: “Automatically forward all Jewish mail to 65 Berlin, Iranische Strasse.”

Elie scanned without reading—her only purpose was to identify the language. She tried to ignore her sense of revulsion—never pausing to look at the name of the writer or what they’d written. Sometimes, when she was trying to fall asleep, she saw phrases from these letters—hurried, terrified lies, extolling the conditions in the camps. But when she scanned them quickly, she noticed nothing—except when she saw the enormous bag marked A, for Auschwitz. It was bigger than the other mailbags and seemed larger than anything this world could contain, as if it had fallen from another universe. Elie always had the sense that she had fallen with it and paused before reading the first letter.

What’s wrong? said the officer.

I’m just tired, she said.

Is that all?

The officer, who loved gossip, always tried to pry into Elie’s past because these days people parachuted into the world as if they’d just been born, with new papers to prove it, and she was no different—the daughter of Polish Catholics, transformed into a German by Goebbels. Her features conformed to every Aryan standard. Her German accent was flawless.

Elie stared at some bolts of wool wedged between two bicycles. Then she went back to sorting letters. The officer lit a cigarette.

You won’t believe this, he said. But a Jew just got out of Auschwitz. He walked past the fence with the Commandant’s blessing.

I don’t believe you, said Elie.

It’s all over the Reich, said the officer. An SS man came to the Commandant and said this guy owned a lab, and the Reich needed it for the war and the guy had to leave to sign over the papers. So the Commandant said he could, and now they can’t find the lab or the name of the SS man. They don’t even think he was real. They call him the Angel of Auschwitz.

My God, said Elie.

Is that all you can say? It’s a fucking travesty. And Goebbels won’t shoot the Commandant. He says he can’t be bothered.

Elie fussed with the strands of the red ribbon on her wrist. She couldn’t take the ribbon off because, along with special papers, it gave her unlimited freedom to travel and amnesty from rape, pillage, or murder. The officer leaned close and offered to untangle the strands. One had a metal eagle on it—the beak was the size of a needle’s eye. He paused and admired the craftsmanship.

Elie let him untangle the ribbon and counted things on the walls: five gilt-edged mirrors, fifteen typewriters, one globe, seven clocks, eight tables, bolts of white cashmere, a mixing bowl, twelve chairs, a tailor’s dummy, five lamps, numerous fur coats, playing cards, boxes of chocolate, and a telescope.

A jumble shop

, she thought.

The Reich can raid everything but heat.

A jumble shop

, she thought.

The Reich can raid everything but heat.

I must get back, she said, standing up. If I see any codes from the Resistance, I’ll let you know.

Stay the night, said the officer, patting a confiscated couch. I’ll keep my hands off you. I promise.

You have more than hands, said Elie.

My feet are safe, too, said the officer. He pointed to a hole in his boots, and they laughed.

As she always did, Elie accepted his offer to take whatever she wanted from the outpost—this time, fourteen bolts of wool, a grandfather clock, the telescope, the globe, ten fur coats, a tailor’s dummy, two gilt mirrors, three boxes of playing cards, and half a kilo of chocolate.

She also accepted his offer to carry everything across the field, where the snow was still soft, and the sky still promised pageants of light. Elie let the officer kiss her on the lips just once and hold her longer than she would have liked. Then she drove deep into the North German woods where pine trees hid the moon.

At one point a thin girl without shoes darted across the road. Elie wasn’t surprised: at this stage of the war, people appeared just like animals. But she couldn’t stop, even to offer bread. There were as many guards as trees. And one rescue was dangerous enough.

The pines grew thicker; wind blew through the canvas roof of her jeep, and Elie’s fear of the dark rose up, along with a terror of being followed. She concentrated on the road as if her only mission were to drive forever.

Alongside her fears ran her shock about the Angel of Auschwitz. Elie always found clever escape routes for people—sewers in ghettos, tunnels below factories. But she’d never contemplated an escape from a camp. She wondered if the angel was a rumor. What better way to annoy the Reich than imply a place like Auschwitz wasn’t foolproof?

Near three in the morning, the road became an unpaved road, jolting the car and making the grandfather clock tick. Elie’s ribbon brushed against the gearshift, reminding her she was tethered to the Reich. She looked in the rearview mirror to make sure she wasn’t being followed and made a sharp turn to a clearing where another jeep and two Kübelwagens were parked near a shepherd’s hut with a round roof. The clearing had a watchtower by its entrance and a well set far back near the forest.

A tall man in a Navy jacket and rumpled green sweater ran out and threw his arms around her. Then he helped her unload the jeep. They brought the telescope, the tailor’s dummy, the bolts of wool, the coats, the mirrors, the chocolate, the playing cards, the clock, the globe, the mailbags, and a hamper of food to the shepherd’s hut. The room had a pallet and a crude wooden table. Opposite the door was a fireplace. To its left was another arched door that opened to an incline. Elie and the officer dragged everything down the incline to a mineshaft and loaded it into a lift. He leaned over to kiss her, but she shook snow from her coat and turned away, caught in thoughts about the angel.

What’s wrong? he said. Does only half of you like me?

All of me likes you, said Elie. I’m just saving the other half for later.

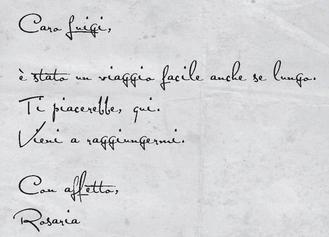

Dear Luigi,It was an easy journey even though it was long.The country is lovely here. Come meet me.Love,Rosaria

Other books

Midwinter Nightingale by Aiken, Joan

On Heartbreak Ridge: Movie Trilogy Prequel Novella (The Movie Trilogy) by Kimberly Stedronsky

Abound in Love by Naramore, Rosemarie

Blue Thunder by Spangaloo Publishing

Shrinking Ralph Perfect by Chris d'Lacey

Perfect by Pauline C. Harris

War of the Magi: Azrael's Wrath (Book 2) by Lewis, Joseph Robert

Looking at the Moon by Kit Pearson

Gone to Ground by Taylor, Cheryl

Meteorite Strike by A. G. Taylor