Heidegger's Glasses: A Novel (10 page)

Read Heidegger's Glasses: A Novel Online

Authors: Thaisa Frank

Do all these belong to Heidegger? he said.

Just one, said Elie.

How do you know?

Because it’s marked, said Elie. She pulled the box close to her.

Does Heidegger have any eye problems?

He might, said Elie, who knew he was only nearsighted.

Then we have to bring him his glasses.

But not without the letter, said Elie. Or Frau Heidegger will have a fit.

What does she have to do with it?

Goebbels met with her, said Elie. That’s why they wrote these orders.

Goebbels met with Frau Heidegger? He’s much too busy.

But he did, said Elie. They had a very long meeting at the Office.

The tick started again, and Stumpf put his hand on his forehead to press it down. But it kept skittering and jumping as though his forehead was on fire. And now he remembered that all five Scribes should answer the letter—a matter that seemed urgent since he’d heard about Frau Heidegger’s meeting with Joseph Goebbels.

The more Elie went on about needing an answer, the more Stumpf’s tick skittered and jumped. Finally he turned to the Scribes and shouted:

I need to see the five philosophers.

For heaven’s sake, said Elie, leave them out of it.

Letters are their job.

And soon, to Elie’s dismay, Gitka Kapusinki, Sophie Nachtgarten, Parvis Nafissian, Ferdinand La Toya, and Niles Schopenhauer were standing around her desk, and Stumpf was reciting the letter and ordering them to answer it.

But we only answer letters to the dead, said Parvis Nafissian.

Or the about-to-be-dead, said Gitka Kapusinki.

Or the almost dead, said Sophie Nachtgarten.

Heidegger’s different, said Stumpf.

Which is why we can’t answer the letter, said Ferdinand La Toya. It’s against the mission.

Then all five leaned on Elie’s desk and began to talk about Heidegger as if Stumpf weren’t there.

He’s all about paths and clearings in the Black Forest, said Niles Schopenhauer. There’s no way anyone can think about that in this dungeon.

Except you need a lot more than fresh air, said Sophie Nachtgarten. He’s a mystic tangled up in etymology.

I don’t agree, said Gitka Kapusinki. He got a lot of things right. But he has no idea how they work in the real world.

This baffling conversation made Stumpf’s tick jerk and jump. He pounded Elie’s desk and recited the beginning of the letter so loudly the whole room could hear:

With regard to your recent remark about the nature of Being, I wanted to emphasize again that it was the distance of my glasses that made me close to them.

The Scribes laughed, and Niles Schopenhauer said they should translate the letter into their invented language, which they called

Dreamatoria

.

Dreamatoria

.

Stumpf waved his hand at Niles. It grazed him on the cheek.

Remember your place, he said. You’re nothing but a fucking Scribe.

Don’t pull them into it, said Elie. It’s not their fault. If anyone catches us bringing a letter, we’re in trouble, and if we don’t bring one, we’re in trouble.

A paradox! said La Toya.

Indeed! said Gitka.

The notion of paradox was too much for Stumpf. He went over to Sonia and asked her to come upstairs. But she said hearing the letter had made her thoughtful, and she wanted to sit at her desk and think about distance.

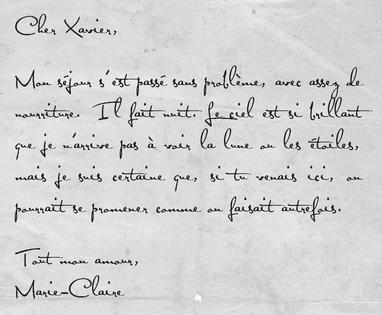

Dearest Xavier,I had a safe journey, with plenty of food. It’s night now. The sky is so bright I can’t see the moon or stars, but I’m sure if you came, we could take walks at night, the way we used to.Love,Marie-Claire

The tick continued when Stumpf went back to his shoebox, skittering in tandem with his brain. With great misgivings and second thoughts, he decided to disobey a strict order and approach a Scribe who was forbidden from answering letters written in German: this was Mikhail Solomon.

When he designed the Compound, Hans Ewigkeit had clustered most of the rooms using the mineshaft as a reference point. If one stood with one’s back to the mineshaft, the kitchen was to its left, the guards’ room and officers’ quarters to its right, and the main room directly opposite. But the cobblestone street went on for thirty meters to dead-end in a wall that concealed an underground passage to the nearest town. And a stone’s throw from this wall was a little white house with four pots of artificial roses, an artificial pear tree, and a lead-paned window. The street had no name, but the house had a number—917—engraved in bronze on the door.

Mikhail Solomon lived in this house with his wife, Talia. They had been designated

Echte Juden

, pure Jews, in charge of answering all correspondence written in the Hebrew alphabet—letters from people the Reich decided were pious. To be sure the letters were in keeping with the motto of

Like Answers Like

, the Solomons lived in a house like the one the interior designer Thor Ungeheur imagined they’d lived in before they were sent to the Lodz ghetto in Poland. They had two small kitchens, impossible to cook in, and were allowed to observe their customs, which adhered to the Reich’s vague understanding of menorahs and a candle in the shape of a braid. They were forbidden from working on Saturday.

Echte Juden

, pure Jews, in charge of answering all correspondence written in the Hebrew alphabet—letters from people the Reich decided were pious. To be sure the letters were in keeping with the motto of

Like Answers Like

, the Solomons lived in a house like the one the interior designer Thor Ungeheur imagined they’d lived in before they were sent to the Lodz ghetto in Poland. They had two small kitchens, impossible to cook in, and were allowed to observe their customs, which adhered to the Reich’s vague understanding of menorahs and a candle in the shape of a braid. They were forbidden from working on Saturday.

The Solomons were an unlikely pair, snatched from the maws of a cattle car about to leave the Lodz ghetto for Auschwitz. Mikhail was a slight, clean-shaven man who wore a skullcap. Talia was a head taller, had a shadow of a moustache, broad shoulders, and red hair in a long French braid. Before the war Mikhail taught ethics at the University of Berlin, and Talia taught English. The Solomons weren’t Orthodox. They ignored Goebbels’s orders about keeping to themselves and came to the main room every day to play word games and barter cigarettes. They also used the main kitchen.

Besides the privilege of a house, Mikhail was the only person besides Elie Schacten who could leave the Compound after midnight. Long after the lottery had been drawn for Elie’s old room, and the Scribes were making love, eavesdropping, and note passing, Mikhail alone could admit he was awake. Then Lars Eisenscher knocked on his door and led him past the main room with bodies on desks, rustling papers, and glissandos of snoring. They took the mineshaft, walked up the incline, and down a stone path to the left of the Compound where they climbed a watchtower almost twelve meters from its entrance.

The watchtower had a steep ladder that led to a platform with a panoramic view of the night sky. And on this platform Mikhail pretended to read the stars. He had explained to the Reich he was a Kabbalist, and Kabbalists need to meditate on the sky after midnight. Didn’t Hitler realize that the stars were angels and could predict the future?

As soon as the Reich heard this, they sent a memo:

Let the Jew read the stars.

Mikhail wasn’t surprised. Everyone knew Hitler conferred with an astrologer about the war, and Churchill consulted one to predict Hitler’s strategies. Mikhail himself didn’t believe in angels or astrology. He only craved fresh air and the boundless freedom he felt when he looked at the sky. It was impervious to war, without trenches, countries, or borders.

Let the Jew read the stars.

Mikhail wasn’t surprised. Everyone knew Hitler conferred with an astrologer about the war, and Churchill consulted one to predict Hitler’s strategies. Mikhail himself didn’t believe in angels or astrology. He only craved fresh air and the boundless freedom he felt when he looked at the sky. It was impervious to war, without trenches, countries, or borders.

Sometimes he liked to imagine each star was a word, and the sky was a piece of paper. Then the stars unfurled into a phrase—a proclamation for just one night. Sometimes he announced it to the main room in the morning. The last one had been

the persistence of fire

.

the persistence of fire

.

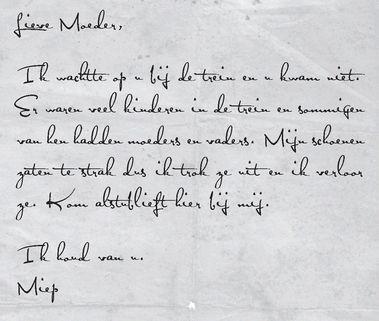

Dear Mother,I waited for you at the train and you didn’t come. Lots of children were on the train and some of them had mothers and fathers. My shoes got too tight so I took them off and lost them. Please come be with me. I love you.Love,Miep

Mikhail’s grandfather, who actually believed the stars were angels, once told Mikhail that whenever he wanted something—a pair of skates or a new coat—he lit a candle at midnight and prayed to the stars. Mikhail found this outlandish and was abashed that since the Reich came into power, he’d begun to wish his grandfather had been right. But if the stars were angels, they were mute, indifferent angels. Never once had they offered help.

The night after Heidegger’s glasses arrived, the stars were dazzlingly clear. Mikhail saw Queen Cassiopeia’s Chair, waiting for Queen Cassiopeia. And Aquarius bearing water—too far away for the water to reach the earth. Six Pleiades were dancing, and the seventh, as always, was hidden.

Other books

A Curious Tale of the In-Between by Lauren DeStefano

Taming McGruff (Book 3, Once Upon A Romance Series) by LeClair, Laurie

Todo va a cambiar by Enrique Dans

The Castle by Sophia Bennett

Refining Felicity by Beaton, M.C.

Betrayal by Gardner, Michael S.

Tigers in Red Weather by Klaussmann, Liza

Blue Heaven (Blue Lake) by Harrison, Cynthia

Prisoner of the State: The Secret Journal of Premier Zhao Ziyang by Adi Ignatius