Heidegger's Glasses: A Novel (8 page)

Read Heidegger's Glasses: A Novel Online

Authors: Thaisa Frank

I’m not your servant, said Stumpf, shoving everything back.

And he left the rosewood room still a burdened man because no one in the Compound took the mission more seriously than he did. Stumpf was sure the idea about answering letters to the dead or about-to-be-dead had occurred to him at the same time it occurred to the Thule Society, just the way two people in the 17th century—he couldn’t remember who—had discovered calculus at the same time. Lodenstein treated the project carelessly, which so bothered Stumpf he often woke in the middle of the night, sure the dead were hounding him. He was sure he could hear them now.

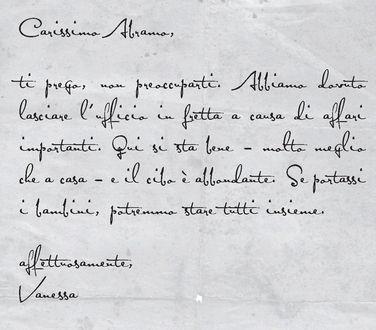

Dearest Abramo,Please don’t worry. We had to leave the office quickly because of important work. Conditions are good—much better than they were at home—and the food is plentiful. If you brought the children, we could all be together.Love,Vanessa

After she left Stumpf’s watchtower, Elie Schacten sat on a wrought-iron bench outside the Compound’s main room. Hans Ewigkeit, with Thor Ungeheur, the Compound’s interior designer, had ordered these benches placed at random on the street. He’d wanted to suggest an affluent city park.

Elie knew Stumpf wouldn’t do anything but hoped she’d planted a seed. She lit a cigarette and stared at a photograph of Goebbels hanging next to the mineshaft. The photograph was five feet tall, just five inches less than his actual height. Goebbels was posed near an unusually small umbrella that made him appear taller. When Elie looked at his face, it was full of hope. But when she just looked at his eyes, she saw a sad, liquid quality. She took out the photographs—of Asher Englehardt and Heidegger, of Asher Englehardt’s ruined shop. She looked at them and put them away.

A few Scribes asked if she was all right, and Elie fobbed them off by leafing through her dark red notebook. Now and then she paused to read something—never more than a fragment—

a forest near the house/ice cracking in the spring

—but was interrupted by Sonia Markova, a Russian ballerina who practiced pliés in a state of eternal melancholy.

a forest near the house/ice cracking in the spring

—but was interrupted by Sonia Markova, a Russian ballerina who practiced pliés in a state of eternal melancholy.

You look worried, said Sonia, sitting next to her.

I’m just tired, said Elie, closing the notebook.

Sonia’s white ermine coat brushed against her cashmere sweater, and for a moment Elie felt caught in Hans Ewigkeit’s dream: she and Sonia weren’t ten meters below the earth in a converted mine, but two well-heeled women in a city park. She was glad when Scribes began to argue in the kitchen and she had an excuse to leave. They all wanted coffee, but no one wanted to brew enough for everyone. Elie ducked under the clanging pots and said she’d make it herself. But the Scribes said she did enough for them and waved her away. So she went upstairs, where Gerhardt Lodenstein was playing his ninth game of solitaire for the day.

Lodenstein knew over fifty games. Among them were Zodiac, The Castle of Indolence, Griffon, Streets and Alleys, Thumb and Pouch, Open Crescent, Five Companions, Seven Sisters, Waste the Same, Mantis, Scarab, Twin Queens, Up or Down, Step by Step, and Milky Way. He played in stacks and cascades and felt a sensual thrill when he could do a full levens. Besides Elie Schacten, solitaire was the only thing that kept him sane. When she came in he was playing Czarina. His compass was on the floor. She put it on the bedside table.

So, he said, is Stumpf your angel?

He didn’t understand a thing, said Elie.

Has he ever?

Not once. But I thought it would work to our advantage this time.

Our advantage?

said Lodenstein. He gave her a sharp look. All I want is to keep the Scribes from a death march.

said Lodenstein. He gave her a sharp look. All I want is to keep the Scribes from a death march.

You’re imagining the worst, said Elie.

Then why do you bother with rescues?

Elie didn’t answer and took off her cardigan. Heidegger’s glasses fell from the pocket. Lodenstein picked them up.

Do you think Goebbels gives a damn if Heidegger gets these? he said. Germany’s losing this war, so what better way to feel good than issue impossible orders?

He doesn’t want the Heideggers to know about the camps, said Elie, taking the glasses back. And if they don’t get what they want, they’ll keep poking around.

He’d handle them if they found out.

He doesn’t

want

to handle them. He wants us to. And the outpost officer is frantic.

want

to handle them. He wants us to. And the outpost officer is frantic.

Lodenstein set a few cards aside. It was a special move called a heel.

You see, said Elie, pointing to the cards. There are always ways to break the rules.

That’s why I like solitaire. It’s not a dangerous game.

Elie stayed by the windows and looked at snow dusting the pines. She wondered if it was snowing at Auschwitz.

It looks like a painting out there, she said.

Except it’s not, said Lodenstein. Who knows how many fugitives are hiding in those woods?

And I could have been one of them, said Elie.

Thank God you’re not.

Except I’m not myself anymore, she said. Sometimes I think even you don’t know who I am.

Of course I know who you are.

You know what I mean.

What Elie meant was that she often felt like two different people. One was Elie Schacten, born in Stuttgart, a translator for the importer Schiff und Wagg. The other was Elie Kowaleski, a student in linguistics at Freiburg.

Elie Schacten had grown up in Germany with nursery rhymes and cooking classes. She was engaged to a soldier killed at the front. Elie Kowaleski had grown up with Polish nuns who beat her fingers until they bled, had parents who found her obstreperous, and a sister she missed every day. The two Elies worked in tandem: The first was cautious, established bonds with the black market and got food for the Compound. The second was dauntless, got more food than people ever meant to give, and smuggled people to Switzerland.

I wish you’d tell me your real last name, said Lodenstein—not for the first time.

It’s a secret, said Elie—not for the first time.

It’s not good to feel like two people, he said.

But I

am

two people. And someday they might ask you the wrong questions. So the less you know the better.

am

two people. And someday they might ask you the wrong questions. So the less you know the better.

They were interrupted by General-Major Mueller, who came in without knocking and shoved a deck of cards at Lodenstein.

What game should I tell Goebbels you’re playing these days? he said. Persian Patience? Odd and Even?

Tell him I’m playing Mueller Shuffling Papers, said Lodenstein.

Go fuck yourself, said Mueller. He slammed the door. They heard his duffel bag scrape against the incline.

You pissed him off, said Elie.

Go out and make up to him, said Lodenstein.

Why? He’s a pig.

I want to keep Goebbels happy.

So even you need the other Elie.

You just know how to charm people, said Lodenstein, taking her in his arms. But you’re always the same to me.

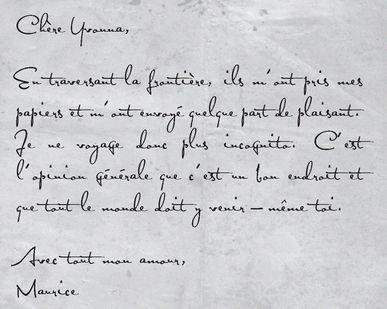

Dear Yvonne,As I was crossing the border they took all my special papers and sent me to a pleasant place. And so I’m not traveling incognito anymore. It seems to be the general opinion that this is a good place and everyone should come, including you.All my love,Maurice

Elie followed Mueller, who looked incongruous with his elegant tooled-leather case and beat-up duffel bag. Outside the shepherd’s hut there was a path of oval stones that led to the clearing. Mueller turned around when he heard Elie’s boots crack the ice.

How lovely to see you, he said and took her arm.

Elie held her arm at a distance and watched his elbow gesture toward the sky. It was a dazzling incandescent blue.

If only we could be like the weather, said Mueller.

Who says we can’t? said Elie.

The war, he said. Rain means waiting to attack, sun means charging ahead, and winter means Stalingrad.

But Stalingrad was last winter.

And it changed winter forever, said Mueller.

Elie tried to free her arm. Mueller pressed closer.

Let me give you some advice, he said. Leave those orders alone.

What orders?

Other books

A Soul of Steel (A Novel of Suspense featuring Irene Adler and Sherlock Holmes) by Douglas, Carole Nelson

Personal Demons 2 - Original Sin by Desrochers, Lisa

Sealed with a Kill by Lawrence, Lucy

Rookie by Jl Paul

Victim Six by Gregg Olsen

Sweet Little Lies by J.T. Ellison

Forests of the Night by David Stuart Davies

Tom Kerridge's Proper Pub Food by Tom Kerridge

Climb the Highest Mountain by Rosanne Bittner

It Gets Better by Dan Savage