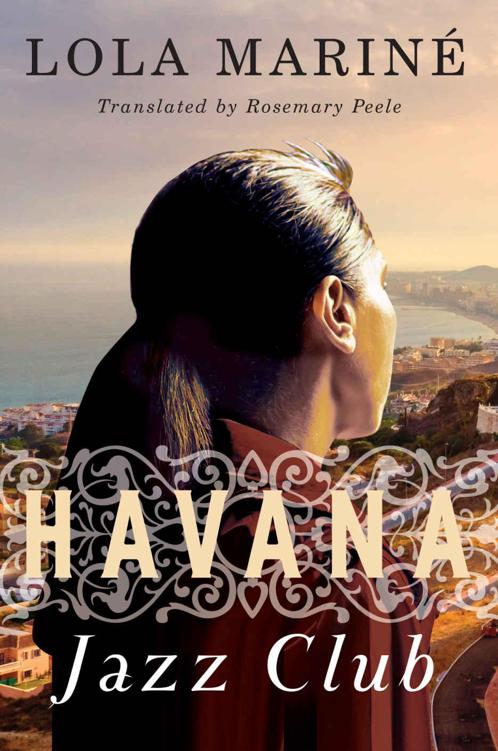

Havana Jazz Club

Authors: Lola Mariné

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, organizations, places, events, and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

Text copyright © 2014 Lola Mariné

Translation copyright © 2015 Rosemary Peele

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher.

Previously published as

Habana Jazz Club

by Kindle Direct Publishing in 2014 in Spain. Translated from Spanish by Rosemary Peele. First published in English by AmazonCrossing in 2015.

Published by AmazonCrossing, Seattle

www.apub.com

Amazon, the Amazon logo, and AmazonCrossing are trademarks of

Amazon.com

, Inc., or its affiliates.

ISBN-13: 9781503945852

ISBN-10: 1503945855

Cover design by David Drummond

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

Billie was born with music. She had suckled Latin rhythms from her mother’s breasts and grew up to the rhythm of the jazz music that flooded every corner of their house. Sarah Vaughan, Ella Fitzgerald, and Billie Holiday took turns each night, singing their peculiar lullabies, which were sometimes tinged with melancholy and often referred to spiteful lovers or resigned hopelessness. Some nights, the happy melodies of Duke Ellington and his orchestra or the shattered, warm voice of Louis Armstrong accompanied by his inseparable trumpet, emanating from the old record player that was her mother’s single greatest treasure, populated her dreams.

Billie grew up with the belief that life had a soundtrack, just like the movies, because she couldn’t remember a single day of her childhood when music hadn’t accompanied every one of her daily tasks. Even out on the street, she was bombarded by a mambo, a

guaracha

, or some bolero, which she would find lurking on every corner.

The first thing her mother, Celia, did every morning when she got up was turn on the record player. And through that distinctive sound—almost a crackling—that the needle made when it slid over the vinyl, the chosen song announced to the family, without leaving the smallest trace of doubt, in what mood the lady of the house had awoken—a thing that was worth noting, especially by her husband.

Celia adored music. She had always loved to sing, and she did so very well; she had a sweet and mellifluous voice, and she knew all her favorite artists’ songs by heart. She sang aloud while she did the endless household chores, her happily bubbling stews tasting even better when she seasoned them with the blues. Sometimes, without realizing, she got carried away and her voice escaped impetuously through the doors and windows of her house—which were always open in her native Cuba—and the echo of her songs drifted across Old Havana.

At other times, she sang very gently. When she was overcome with sadness or she was worried about something, the music appeared to comfort her, as though the words were a prayer drawn from the corner where she had put up her little altar and delivered to the saints who protected her home.

When things became so difficult that she could barely feed her youngest, tears would clog her throat, and she could barely sing a single note, anxiety and futility smashing her voice and her songs into pieces. In such moments, she would turn to Bebo Valdés, or Cachao, or the Trio Matamoros, who would lift her spirits and the rest of the family’s with their Caribbean joy.

“Music is nourishment for the soul,” she would say, when they needed to distract their brains—and above all their stomachs—from hunger.

Celia had once dreamed of being a jazz or blues singer and going to the United States to make her fortune, to Chicago or New Orleans, where so many Cuban artists were enjoying great success in those years. But she had never dared to voice her dreams out loud. Besides, she had never had the opportunity, or the time, to choose her destiny. Barely knowing how or why, she had found herself married one fine day to a handsome and persistent young man named Nicolás and was soon rocking her first child in her arms. The second followed shortly, and a few years later—when no one was expecting her—Billie was born.

Celia chose the name. It was in honor of Billie Holiday, the African American jazz singer who had passed away shortly before.

They said that Holiday had a limited register, but the intensity and emotion of her voice had made her a unique and inimitable soloist of international fame. Celia had learned Holiday’s songs in English by listening to them over and over, and though she didn’t understand the lyrics, she sang them with great feeling. Everyone thought she had a similar timbre, and that she even looked like the famous singer: she had the same dark complexion and was equally beautiful and voluptuous. Celia was flattered and tried to accentuate the similarities whenever possible. She copied the singer’s hairstyle, the way she dressed, and her singular manner of singing.

Celia had avidly followed the news about the singer’s wretched and tormented life. Even in Holiday’s final days, when her voice had become as fragile and brittle as her physical appearance, she never lost her ability to move people with her songs. Celia was deeply moved by the singer’s premature passing and awed by how much music she had produced during her brief and perilous life.

So, when Celia bore a daughter, the father’s protests over their baby’s name were all in vain. He argued that Billie was a man’s name and wasn’t appropriate for such a pretty little girl. He wanted to name her Cassandra, after the beautiful Trojan princess beloved by Apollo himself. When Celia refused to back down, he tried to negotiate for a combined name: Cassandra Billie, he suggested. That way, her stubborn mother could call her whatever she liked in the intimacy of their home. But Celia wouldn’t hear of it. The girl’s name was finally, definitively entered in the civil register as Billie.

The little girl arrived in the world at a moment in time when her country was immersed in a beautiful dream come true. Only a few years later, it would spiral into a seemingly endless nightmare, whose unfavorable consequences were barely starting to show when she was too young to understand what was happening. The girl, oblivious to the problems surrounding her, grew up happy, protected, and pampered by her parents and two older brothers who would do anything for her. It was the only world she had known, and she embraced it as a matter of course. She accepted the long and inevitable lines for everything, the ration cards, and the lack of basic necessities, blissfully ignorant that life could be otherwise. She enjoyed simple things like leaning out the window and contemplating the stars, so shiny and brilliant in the intense blackness that enveloped them, or playing hide and seek with her brothers with the house completely dark. Unlike other children, Billie had always liked the dark. Maybe because that was the time of day when her mother, after finishing her thousand and one chores, would sit down in the kitchen and relax. If she was in a good mood, she would sing gently while Billie listened, entranced. Often she would join her mother, and together they would sing their favorite songs, illuminated only by the moonlight coming through the window. And then they would be surprised by the delighted applause of the rest of the family, who had gathered, stealthy and silent, to listen to them.

Celia always bragged about her daughter’s voice. Brimming with satisfaction, she claimed that Billie sang much better than she did, and she was always urging her daughter to practice her singing and piano. But Billie couldn’t help but notice that the more she progressed, the sadder her mother seemed. Despite her initial delight and pride in her daughter’s talents, she always ended up lamenting that Billie, like her, would not have any opportunities if things didn’t change. Her children, she complained, had been born in the wrong place at the wrong time, and she blamed herself for not being bolder in her youth. Instead of fighting for her own dreams, she had caved in to the expectations of others and let herself be swept along by life. Though she adored Nicolás—she couldn’t have asked for a better husband or father for her children—she believed she had married too young. He was a good and patient man, a man who hadn’t so much as hesitated when his entire family had expressed their disapproval of his fiancée’s mixed race. Which explained why he had been so determined to get married as soon as possible—and Celia seemed to agree.

Still, she held it against him. If they hadn’t rushed into things, maybe their family would have a better life.

Whenever she voiced her thoughts aloud, it invariably provoked her husband’s anger.

“Shut up, girl! You don’t know what you’re talking about!” he would snap at her. “The homeland deserves every sacrifice, no matter how large!”

“The homeland, the homeland,” she would mimic. “Every mouth is full of the homeland. My only homeland is my family, and the only mouths that I want to see full are those of my children.”

“Your children have everything they need,” he would shoot back. “Would our daughter ever have been able to go to music school before?”

“Well, I suppose you have a point there,” she conceded, before going on the attack again. “But I can’t buy her ice cream when she wants it, or a pretty dress, or even any decent fabric to make her one myself. And why did they have to ban jazz? Who was it hurting?”

“Aha!” Nicolás exclaimed. “That’s what’s really bothering you—that they banned your favorite music.”

That was how most of their arguments, which were heated and frequent, started. And then everyone got involved. The male children each took the side of one parent or the other—not always the same one, since they were just playing devil’s advocate—and each would try to defend their parent’s point of view. In the end, their father would impose his authority by ordering everyone to shut up. Recognizing that his wife was impossible, he eventually resolved the matter with some conciliatory gesture toward her.

“Don’t be like that, Mami,” he would say, putting his hands on her shoulders and planting an affectionate kiss on her forehead. “Things will get better soon. You’ll see.”

“I hope you’re right,” she would sigh and then return to her chores.

Little Billie didn’t really understand what they were talking about or why they were so angry, but a dream took root deep in her heart: maybe one day she would be able to make her mother’s dream come true and bring her to the United States, that marvelous country so near and yet so far—at least that was the impression she got from everyone else.

When Celia’s husband wasn’t there to get angry at her for filling the girl’s head with what he considered to be nonsense, she told her daughter that over there, on the other side of the ocean, people were happy because they had everything they needed. They could eat as much as they wanted, buy stylish clothes, and live in beautiful houses with lots of modern appliances. And they didn’t need to stand in line for hours, because they had so many stores brimming with goods, so many theaters and restaurants, so many bars and jazz clubs that everybody could go wherever they wanted whenever they liked, without needing to make reservations ahead of time, or worrying that a place would be full, or that they would be out of whatever they wanted to order. There were always new records to buy, unlike on the island, where they had to listen to the same songs over and over again for years because they couldn’t get new recordings, let alone those of American singers.

Whenever a record got scratched or broke, Celia always got enormously upset. She would wrap it up carefully and put it back in its case, in a kind of record graveyard she had in her chest of drawers that she forbade anyone from touching. Sometimes she unwrapped the records and contemplated them nostalgically, perhaps recalling the joy she had felt when listening to them. Afterward, she would put them back and let out a long sigh of resignation.