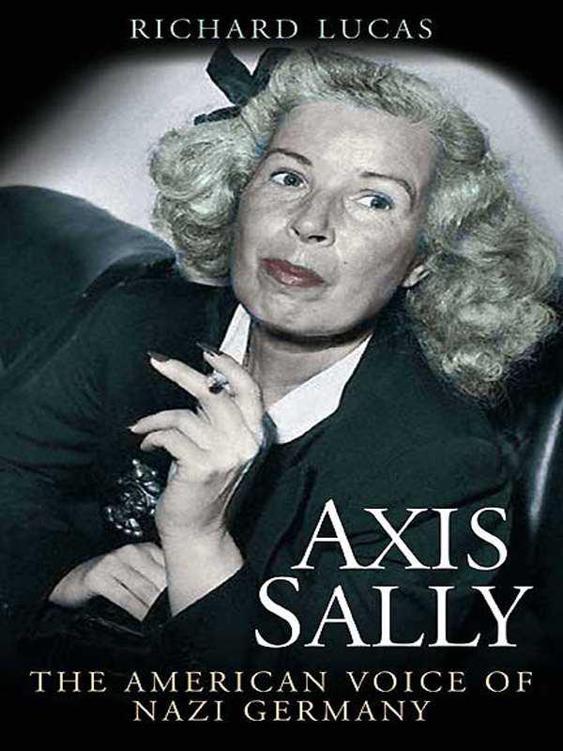

Axis Sally: The American Voice of Nazi Germany

Read Axis Sally: The American Voice of Nazi Germany Online

Authors: Richard Lucas

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Bisac Code 1: BIO022000, #Biography, #History

Published in the United States of America and Great Britain in 2010 by CASEMATE

908 Darby Road, Havertown, PA 19083

and

17 Cheap Street, Newbury, Berkshire, RG14 5DD

Copyright 2010 © Richard Lucas

ISBN 978-1-935149-43-9

eISBN 978-1-935149-80-4

Cataloging-in-publication data is available from the Library of Congress and the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed and bound in the United States of America.

For a complete list of Casemate titles please contact:

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (US)

Telephone (610) 853-9131, Fax (610) 853-9146

E-mail: [email protected]

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (UK)

Telephone (01635) 231091, Fax (01635) 41619

E-mail: [email protected]

For Jordan and Taylor

Preface

While browsing through a website devoted to rare and historic audio clips in 2003, I first heard the voice of Axis Sally. This woman (Mildred Gillars) was the notorious Nazi propagandist whose theme song

Lili Marlene

became an international favorite during and after the war. Despite her undeniable skills as a broadcaster, the recording also featured a vile anti-Semitism rant. Insinuating that Franklin Roosevelt was a homosexual surrounded by Jewish “boyfriends,” her words were jarring and repulsive. Yet I wondered how Mildred Gillars, who described herself as a “100% American girl,” became a willing mouthpiece for a genocidal regime. How did this woman with middle-class Ohio roots end up on the wrong side of history, convicted of aiding the Nazi regime and betraying her country? I looked for a biography that answered the question, but none existed. Books on the subject of treason mentioned her in passing and tended to focus on her illicit relationship with a former Hunter College professor who served as her “Svengali.” Her

New York Times

obituary in November 1988 focused on the “

frisson”

her somewhat scandalous testimony caused at her 1949 trial.

As I listened to the Axis Sally audio clips that first day, I noticed that one of the recordings featured another woman with an American accent. Her on-air sidekick addressed her as “Sally” but the voice was clearly not that of Mildred Gillars. Aware of the circumstances that led to the conviction of Iva Toguri d’Aquino as the one and only Tokyo Rose (in fact, there had been several other women employed by Japanese radio who broadcast under the moniker “Orphan Ann”), I wondered how many other Axis Sallies there might have been, and whether any of those women were punished as Gillars and d’Aquino were.

A visit to the National Archives in College Park, Maryland to look at the Department of Justice’s “Notorious Offenders” case files on Axis Sally, as well as a telephone conversation with John Carver Edwards (the author of the excellent 1991 book

Berlin Calling,

about Americans who broadcast for the Third Reich) convinced me to write a factual, documented biography of Axis Sally. Over the next seven years of research and writing, I discovered a deeply flawed but fascinating woman whose thirst for fame led her to the heart of Hitler’s Germany; whose hope for love and marriage convinced her to remain; and whose inner strength compelled her to survive in the death-strewn shelters and cellars of defeated Berlin.

In my younger years, I was a devoted listener to shortwave radio. The radio waves were a battleground of the Cold War in those days. Radio Moscow, Radio Peking, Radio Liberty and Radio Free Europe were propaganda powerhouses that fought for the hearts and minds of countless millions for whom radio was their only link to the developed world. In the darkest and farthest reaches of the earth, the signal from the shortwave transmitters represented nations and peoples and political ideologies. It was Joseph Goebbels who envisioned the power of the medium long before the advent of the Second World War. By 1940, Berlin’s foreign radio service sang the praises of Adolf Hitler and the new Germany twenty-four hours a day in twelve languages. An unemployed American named Mildred Gillars stepped into that burgeoning radio empire and became, along with William Joyce (“Lord Haw Haw”), one of the regime’s most effective propagandists.

Today, radio is arguably one of the most pervasive means of political persuasion. One wonders how a woman with the innate talents of Mildred Gillars would have fared in her native land in a more forgiving time.

Richard Lucas

September 2010

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank the many people whose dedicated assistance made this book a reality. First and foremost is Rita Rosenkranz of Rita Rosenkranz Literary Agency, whose faith in this project has been nothing short of heroic. Martin Noble of AESOP, Oxford, UK provide proofreading, editing and became a friend over the course of five years. Kay Schlichting and Emily Haddaway of the Ohio Wesleyan University Historical Archives were extremely helpful in the process of researching Mildred Gillars’ college years. Gail Connors of the Conneaut Public Library in Conneaut, Ohio provided a wonderful selection of contemporaneous newspaper accounts and items from high school yearbooks of long ago. Faye Haskins and Jason R. Moore of the Washingtoniania Collection of the District of Columbia Public Library located photographs from the defunct Washington Evening Star collection. These and so many other photographs would be lost to history without their dedicated care and maintenance. Mr. John Taylor and the staff at Archives II in College Park, Maryland deserve much thanks; as well as the very helpful staff of the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress.

Paul Beekman Taylor and Walter Driscoll were extremely gracious as I traced the connection between Mildred Gillars, Bernard Metz and the Gurdjieff movement. I also owe a debt of gratitude to the journalists who tracked the story of Axis Sally. First, the late Ambassador John Bartlow Martin, whose papers possessed the only (albeit abridged) copy of the original trial transcript. Helene Anne Spicer generously shared her memories of interviewing Axis Sally. I am most grateful to Iris Wiley, Jim Dury and James Sauer who took the time to speak to me and remember Mildred Gillars’ final years.

Most importantly, I thank my wife Sachi for her love and understanding throughout this experience; our two sons, Jordan and Taylor, who no longer have to ask “When will your book be finished?” Jordan, especially, deserves thanks for patiently spending many hours in libraries and archives near and far. Thank you to my parents, Richard and Gail Lucas, for their love and support.

Also, I would like to express my appreciation to:

Alexander Library, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey; Archives II, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park Maryland; Beinecke Library at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut; Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor Michigan; Bishop Watterson High School Alumni Office, Columbus Ohio; Bishop Watterson High School, Columbus Ohio; Camden Historical Society, Camden New Jersey; Christine Witzmann, translator; Conneaut Public Library, Conneaut Ohio; District of Columbia Public Library, Washingtoniana Division, Washington DC; Harry S. Truman Presidential Library, Independence, Missouri; Hunter College Archives, New York, New York; John Carver Edwards; Molly E Tully; Jennifer Stepp of

Stars and Stripes;

Dr. Joachim Kundler; Library of Congress Manuscript Collection, Washington DC; Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library, Austin Texas; Maine State Archives, Portland Maine; National Archives, Washington DC; Newspaper Archives; New York Public Library, New York, New York; Ohio Historical Society, Columbus Ohio; Paul Robeson Library, Rutgers University, Camden, New Jersey; Spike Lee; The late Stephen Bach for his encouragement; University of Delaware, Newark, Delaware; Guy Aceto, Weider History Group; Bill Horne, Karen Jensen and Caitlin Newman of

World War II

magazine.

Prologue

January 1949

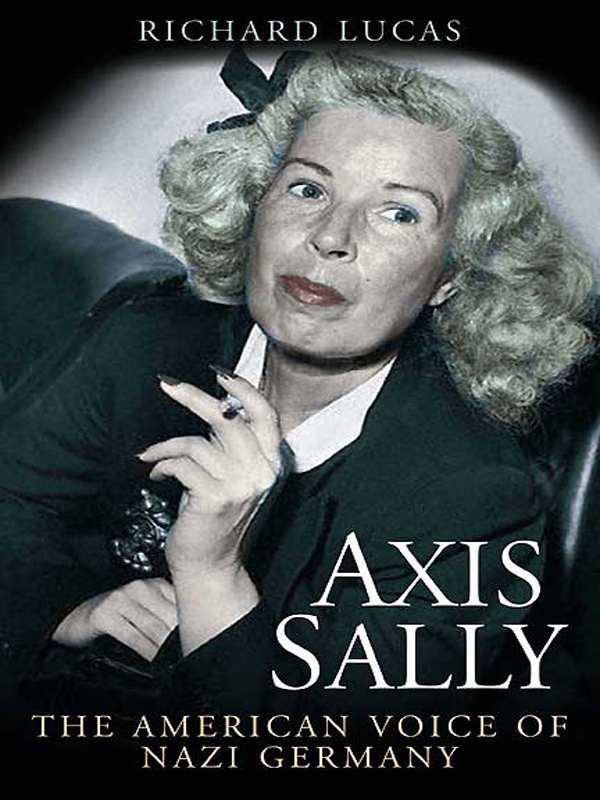

: The US District Court in Washington, DC is teeming with reporters, photographers and curious onlookers. At the center of the mass of popping flashbulbs and shouting newsmen is a silverhaired former showgirl named Mildred Gillars, better known to thousands of GIs as “Axis Sally.” Facing a possible death sentence for treason, the only crime specified in the United States Constitution, she is on trial for broadcasting radio propaganda aimed at demoralizing American troops in their struggle against Nazi Germany.

The world had changed since Axis Sally made her last broadcast in a besieged Berlin radio studio. Deteriorating relations between the victorious Allies preoccupied the postwar world. Communism and subversion from within was the latest threat to the American way of life. The trial of Axis Sally was front-page news, but it was a front page shared with headlines of the entry of Mao Tse Tung’s forces into Peking and the continuing Cold War crisis over Berlin. Internal scandals had rocked the nation, including former Communist Party member Whittaker Chambers’ revelation that Soviet agents, including senior State Department official Alger Hiss, had infiltrated the United States government and sabotaged foreign policy. President Harry S. Truman barely survived Governor Thomas Dewey’s bid to unseat him and end sixteen straight years of Democratic rule. Faced with an uphill electoral battle, the Truman Administration needed to show that the President knew how to deal with America’s enemies.

Two months before the November 1948 election, two infamous figures of World War II returned to the United States to face trial. One was the Japanese-American Iva Toguri d’Aquino, one of several women who worked for Tokyo radio during the war and called herself “Orphan Ann.” The soldiers and sailors in the Pacific theatre called her “Tokyo Rose.” The other woman was a lesser-known but equally reviled American radio broadcaster who worked for Berlin’s

Reichsradio

. Since March 1946 she had languished in an Allied internment camp without charges or the aid of counsel. On the radio, she went by the name Midge, but to the soldier in the field she was “Axis Sally.” Her signature theme song, “Lili Marlene,” was a worldwide hit, and she captured the imagination of the foot soldier with her seductive, lilting voice. Accompanied by a live orchestra playing the GIs’ favorite jazz and swing music, Axis Sally had an audience of literally millions, despite the vile anti-Semitic propaganda she often offered on the side.