Guilt in the Cotswolds

Read Guilt in the Cotswolds Online

Authors: Rebecca Tope

REBECCA TOPE

Dedicated to Pat and in fond memory of Beulah.

Also with special thanks to Daphne Abbley for help with Chedworth topography

- Title Page

- Dedication

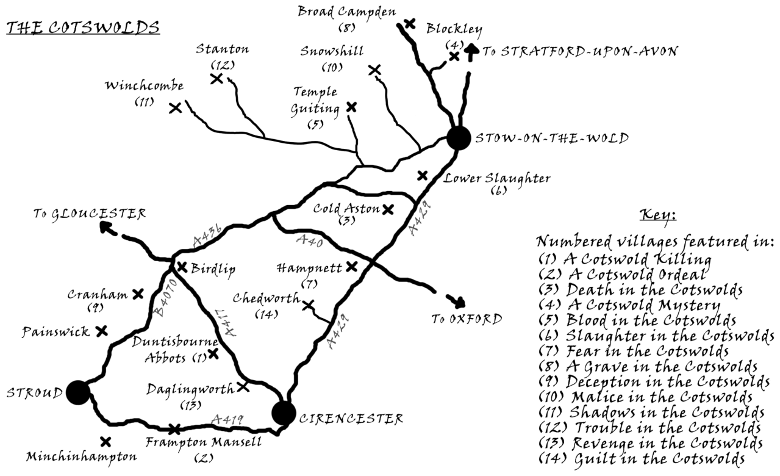

- Map

- Author’s Note

- Prologue

- Chapter One

- Chapter Two

- Chapter Three

- Chapter Four

- Chapter Five

- Chapter Six

- Chapter Seven

- Chapter Eight

- Chapter Nine

- Chapter Ten

- Chapter Eleven

- Chapter Twelve

- Chapter Thirteen

- Chapter Fourteen

- Chapter Fifteen

- Chapter Sixteen

- Chapter Seventeen

- Chapter Eighteen

- Chapter Nineteen

- Chapter Twenty

- Chapter Twenty-One

- Epilogue

- By Rebecca Tope

- Copyright

As with other books in this series, the privately owned properties in the story are products of my imagination, with the exception of the large barn on the road to Yanworth. That does exist.

Drew Slocombe was searching for a care home for the elderly on the outskirts of Stratford-upon-Avon, using a satnav for the first time. His daughter Stephanie, nine years old, had shamed him into it. His shame only increased as he realised how much easier it made the task than it would have been roaming the streets with the help of an inadequate map.

Mrs Rita Wilshire was waiting for him, along with her son Richard. Together they were to draw up a prepayment plan for Rita’s funeral. When the time came she was to have a grave in Drew’s burial ground near Broad Campden – assuming it was fully operational by then. Otherwise, she was content to rest in the Somerset field known as Peaceful Repose, where Drew had already buried close to seven hundred people in the years since Stephanie had been born.

It was early September and the sun was shining. At Richard’s suggestion, they settled on canvas chairs

under a handsome cedar and conducted the business in the open air. ‘Rather as my funeral will be,’ smiled the old lady. ‘I do hope there’ll be fine weather for it.’

Drew responded warmly, pleased to have such a stalwart customer, who accepted the certainty of her own death while expressing a hope that it would not be unduly soon. ‘I would think I might last another five years,’ she had said at the start. ‘There isn’t a great deal wrong with me, apart from my legs.’

‘You’ll see your centenary,’ her son assured her, not quite so phlegmatic about the matter. Richard Wilshire struck Drew as a rather dull character, rendered uncomfortable by this deviation from the usual practice. Not so much the advance planning as the choice of an unorthodox manner of disposal. His mother insisted on a cardboard coffin and no religious input. As people so often did, she began to reminisce about previous funerals she had experienced. ‘My sister died very young. There was a great deal of pomp and circumstance, no expense spared. But she was just as dead in the end. Poor Dawn. She’d be ninety-six now. I still remember her birthday every year.’

Drew ran through the costings of the services he could provide, but counselled against fixing too many details at this stage. ‘Leave something for your son to do,’ he said. ‘Like deciding about music.’

‘I’ve always liked the idea of a lone Scottish piper,’ she said with a distant gleam in her eye. ‘But I wouldn’t insist on it.’

Richard Wilshire rolled his eyes, and gave her a gentle poke in protest. ‘I make no promises,’ he said. ‘Since we don’t possess a drop of Scottish blood between us.’

‘Irish, then. Or even an English one. I don’t see that our blood matters, anyhow. It’s just a lovely haunting image.’

The business concluded, Drew stayed a little while longer, because he was in no rush and he liked these people. Mrs Wilshire had only been in the home for a week or so, and was still intoxicated by the changes to her life. ‘I seem to get the prize for the most compos mentis,’ she laughed. ‘But there are two other excellent bridge players. I’ve only won two rubbers so far. My partner isn’t too hopeless, luckily. She was delighted when I arrived, and they could make up a table. We’re both improving considerably.’

‘It’s a lovely spot,’ said Drew, looking around. The town of Stratford was close by, but the home had generous grounds with several large trees and flower borders. ‘Where did you live before?’

‘In the Cotswolds. A village called Chedworth. I keep expecting to be overcome with homesickness, but so far everything’s far too pleasant here for that to worry me. I admit I miss some of my things, and it’s very strange knowing I no longer own the walls around me. I hadn’t appreciated how much ownership matters. Probably a very incorrect attitude these days, but there it is. And besides, the house is still there, and Richard would never sell it while I live. Would you, dear?’ There

was a hint of challenge in her eye, thought Drew. Or perhaps something even darker, like a threat.

Richard sighed and shifted in his canvas chair. ‘Not unless we run out of cash, and then there won’t be any choice. This place isn’t cheap, you know.’

‘And the family isn’t poor. You’ll get the house eventually. I just couldn’t bear to think of other people in it while I live.’

Richard sighed again. It was clear to Drew that he thought the old lady was being unreasonable.

The subject changed, and Mrs Wilshire pointed out her room, on the ground floor with a window overlooking the lawn. ‘My pathetic legs qualified me for the ground floor,’ she said. ‘It’s not long now before I’ll be needing a wheelchair nearly all the time.’ She had made it to the garden seat with the aid of two sticks, at a very slow pace, the two men following attentively behind.

Shortly afterwards, Drew made his departure, with Richard Wilshire accompanying him to his car. ‘Back in a minute, Mum,’ he said.

‘No hurry, dear. I’m quite all right here. Thank you, Mr Slocombe. I don’t expect I’ll see you again, although that would be a pity. I very much enjoy your company.’

Drew nodded a rueful agreement. ‘Perhaps I’ll drop in on you one day,’ he said. ‘If I’m ever this way.’

‘Oh yes – do. I’m sure we could always find plenty to talk about.’

Richard waited until they were out of earshot, standing beside his big Honda four-wheel drive. He bent down and felt underneath the chassis, below the driver’s door. ‘Sorry,’ he said. ‘It’s a habit I’ve got into. I’ve lost so many car keys in my time. Now I just attach them like this.’ He showed Drew a small metal box that had somehow stuck magnetically to the car. ‘And I keep two spare sets at home for good measure.’ He pulled a self-deprecating face.

‘Seems like an excellent idea to me,’ said Drew. ‘So long as the magnet’s nice and strong.’

Richard then began to speak rapidly. ‘It was very good of you to come like this. I know you’re based in Somerset. This must be taking up virtually the whole of your day.’

‘No problem,’ Drew assured him.

‘The thing is, we’re such a small family, and so many of Mum’s friends have gone now, that it seemed to make sense to get all this settled. I just hope she hangs on until you’ve opened the new burial ground. She’d be so much happier close to her old home.’

‘Chedworth – is that right?’

Richard nodded. ‘You heard her. There’s a great big house standing empty, except it’s not actually empty at all. It’s still full of all her stuff. She could only bring a tiny fraction of it here with her. I need to find somebody to deal with it, I suppose. Though Mum seems to think it’s fine as it is. She’s a bit irrational where that side of things is concerned. There’s no way I can just get a

clearance outfit to take it off our hands. I dread the day when we have to sell the house, but if she lives more than a year or so, we’ll have to, to pay for the home.’

‘So what would “dealing with it” actually entail?’ Already Drew was having an idea.

‘For a start, I need to know what’s there. It goes back more than half a century. I was born there, and as long as I can remember there’ve been wardrobes and chests stuffed with all kinds of clothes and linens and I don’t know what. Not to mention the attic, which has precious heirlooms, according to Mum. I can’t just leave it all, can I? Much as I might like to,’ he added in a low tone.

‘I might know someone who could help,’ said Drew. ‘If you’re interested.’

Thea was lost; lost and late. It was getting dark and the narrow lanes of Chedworth began to close in on her, the village seeming to come to an end only to start again a little further on. She should have paid better attention to the instructions, instead of blithely assuming she knew the area well enough by now to avoid any difficulty. It had become apparent in the past five minutes that there was both a Chedworth and a Lower Chedworth – which came as a big surprise. Small roads wandered off in all directions, including dramatic downward plunges. Richard Wilshire would be waiting impatiently for her in the stone house set on a small road that went nowhere, close to the church. He had ordained five o’clock as the required moment for her arrival. ‘Then we can settle you in for the night,’ he had said, with a laugh that had a trace of snigger in it. His instructions, taken down during a phone call, were scribbled on a scrap of paper beside her. ‘Next left after Hare and Hounds pub. Right at the Farm Shop – straight

through Chedworth until Seven Tuns pub.’ No hint of distances or useful landmarks. She had met a T-junction soon after the right turn, of which there was no mention in the instructions. A defunct red telephone box beside the road had ‘Defibrillator’ blazoned across it, which made her smile. And then the road had carried on and on, around bends and up hills, passing the usual old stone houses with no lights on inside. Anyone, even the most unimaginative, could quite easily believe themselves to have slipped back a century in time. The existence of motorways, airports, bright lighting and high speed had all faded into a far-off realm. Here in this monochrome twilight world, it was easier to revert to a slower, simpler mode. As if to emphasise this, there were signs announcing ‘Twenty is Plenty for Chedworth’ in reference to the speed limit.

It was half past five in early October, which was still an hour short of the moment the sun sank over the edge of the world. But it was a cloudy day and there were trees and high banks and houses on all sides, closing out the lingering light. It felt later than it was. ‘Not sure I like the atmosphere here,’ she muttered to Hepzibah, her constant companion. The spaniel on the passenger seat gave her a liquid look of sympathy. But the houses were as lovely as those in most other Cotswold villages, some of them impressively old and weathered. As she hunted for the church, which surely ought to be on an elevation somewhere visible, she passed clusters of closely packed homes, with never a glimpse of a human being. Seconds later she found herself in virtually open

country, with no buildings visible. This lasted only a short time before another typical house came into sight, followed by several more. The stop-start nature of the place was disorientating.

Chedworth, then, was nothing like Stanton or Daglingworth, Hampnett or Broad Campden – all of which she had come to know in the past year or so. All of which were also remarkably close by, many within walking distance. The way each settlement could acquire so distinct a character was a mystery.

Richard Wilshire was in his late fifties, a solid man of limited horizons. That much Thea had gleaned from information received from Drew Slocombe, her soon-to-be husband and acquaintance of Mr Wilshire. It was thanks to Drew that this commission existed in the first place.

‘He’s got an aged mother who’s just moved into a residential home,’ Drew had explained. ‘She heard about the natural burials, and came to me to arrange her funeral when the time comes.’ Drew had achieved the first stages of establishing a second burial ground in the heart of the Cotswolds, taking pre-planned customers, but so far only one grave lay there. In the process of funeral arranging, it had transpired that Old Mrs Wilshire was leaving behind a substantial house containing a lifetime’s possessions. Her son found himself unequal to the task of sorting these items into any meaningful categories. Young Mrs Wilshire – Daphne – no longer regarded the fate of her mother-in-law as relevant. She and Richard had separated five years previously and she was living

with a man called Nick. ‘Are you keeping up?’ Drew had checked with Thea at this point.

‘Easily.’

‘Good, because there’s more.’ He went on to report that there was a daughter named Millie who was twenty-five and – according to her father – so completely appalled by the treatment of poor old Granny that she couldn’t bring herself to go near Chedworth ever again. ‘All of which explains why a certain Thea Osborne is sorely needed,’ he summarised. ‘It might not be exactly house-sitting as we know it, but it’s well within your capabilities.’

She had given him a look. ‘You’re telling me the job has expanded into that of house-sorter and house-clearer, as well. Which might include heavy lifting. Do I get paid extra?’

‘I left that to you to negotiate. I will, of course, come and help with anything heavy.’

Her reply was a familiar one. ‘How will you find the time to do that?’

‘I’ll manage it somehow,’ he said, as usual.

Drew and Thea had been together – emotionally if not logistically – for well over a year. The summer just ended had seen them spending more and more time as a family, with his two children rapidly accepting her as a fixture. Their wholehearted enthusiasm for her and her dog was almost unnerving. The first week of their school holidays that summer had been spent with Thea in a house-sit that had passed so idyllically she

sometimes wondered if it had all been a dream. The four of them squatted in a large Cotswold house in Farmington in the most perfect weather with a pack of Siamese cats. On the last day, Drew had recklessly suggested marriage. In a surge of euphoria, Thea had accepted. Three months later, she was still uncertain as to whether it would ever actually happen.

The Seven Tuns pub occupied a site near another T-junction. Peering at the final words of her directions, Thea read, ‘Left, then follow road past church. House on left, easy parking.’ Not seeing the church, she drove blindly to the left, up a steep little road that showed virtually no sign of having changed since before cars were invented. Suddenly, the church was right beside her, and all became clear.

She finally knocked on the door at five-fifty. Richard Wilshire brushed aside her apologies for lateness and led her into the living room. ‘You come well recommended,’ he assured her. ‘Good in a crisis, they said about you. Ready for anything.’

She flinched at the

they

. Who else, other than Drew, had been talking? ‘It isn’t exactly what I’m usually asked to do,’ she reminded him. ‘There are professionals for this sort of thing. They take all the stuff in return for leaving a nice empty house.’

‘I don’t want that. This isn’t about clearing the house. We’re not disposing of anything other than absolute rubbish. First, I need an inventory.’ He gave

an embarrassed laugh. ‘I lived here all my life, until I married, but I still have no idea what’s in some of the cupboards and boxes. It never really occurred to me to wonder. But now – well, I can’t leave it any longer.’

Thea attempted to look capable, sympathetic and responsible all at the same time.

‘Be warned,’ Mr Wilshire went on. ‘My mother lived here for seventy years and there are places that probably haven’t been touched for most of that time. How are you with spiders?’

‘Not great,’ she confessed. ‘But better than I used to be.’

‘The attic is the worst. Mum hasn’t managed the stairs for a few years now. I should have gone up there myself, but I never got around to it. Take a killer spray with you, if you like.’

‘No, no. I don’t like to kill the poor things. I’ll be all right if I’m forewarned. The dog sometimes catches them for me, if they’re really huge.’

They went on to discuss the procedure she was required to follow. ‘I don’t think there’ll be very much rubbish, but what there is can go straight into bin bags,’ he said. Then he suggested she set aside items of obvious value; sort through papers (important and otherwise), make a list of items that were broken but potentially useful, and another list of whatever she found in the unexamined cupboards and boxes. She wrote much of it down and asked several questions.

‘I understand Mr Slocombe’s going to join you at some point,’ he said.

She noted the formality with interest, having assumed the two men were on better terms than that. ‘He’ll try,’ she said. ‘It won’t be easy for him to get away if things are busy.’

‘I’ve prepared the main bedroom for you.’ His tone implied that this had been a tremendous achievement, for which she owed him much gratitude. ‘Turned the mattress over, so it ought to be okay.’

‘Thanks.’ Visions of an incontinent old woman sleeping on that mattress until a month or two ago made her uneasy. But it sounded as if all the other rooms were even less habitable.

‘Listen,’ he said with a tormented look, ‘I know it’ll be hard work, and I should be doing it myself. All this stuff – it doesn’t matter to me. I’m not sentimental about most of it. But there’s sure to be a few …

triggers

, if you know what I mean. Things I’ve forgotten, from when I was a kid. There was a time when I tried to get her to throw stuff away, but I gave up long ago. Since then I’ve just closed my eyes to it, and stuck to the routine maintenance business. You know – making sure the electrics are okay and the plumbing works. The house is in a mess, basically. It hasn’t been decorated for decades. I made her take up all the rugs, in case she tripped and fell. They’ll be up in the attic. But I know I could have done a lot more …’ He tailed off miserably.

Thea looked around the living room, where they were sitting together on a shabby old sofa with the dog between them. Richard Wilshire evidently saw no reason

to protest at a spaniel on the upholstery. The wallpaper was faded. There were piles of magazines and books on a window seat, and a clutter of old-fashioned furniture on all sides. The curtains were dusty and the skirting boards grimy. ‘Didn’t she have a home help or something?’

He shook his head. ‘A girl came in once a week for a bit, but they fell out. My mother liked to think she could do it all herself. She never got the hang of the vacuum cleaner, though. Or the splendid new washing machine. She always loved the twin tub, but it died a couple of years ago. She’s stuck at about nineteen seventy, in a lot of ways.’

‘She washed clothes by hand?’

‘Mostly, yes. I supervised a big wash in the machine whenever I came over – sheets and bigger things. She always used an antique carpet sweeper. It does work surprisingly well.’ They both glanced down at the floor, which was quite acceptably clean.

There was something rather nice about it, Thea discovered. A little island of social history, ignoring such new-fangled developments as automatic washing machines. ‘I don’t suppose she has a computer?’ she said.

‘Oddly enough, she has. She had email almost from the start – must be twenty-five years or so now. She’s kept everything on discs, all these years. Most of them are obsolete, of course. She’s got a smart new laptop now. She’s determined to keep up with relatives and old friends. Apparently half the residents in the home have got mobiles and tablets and the latest gadgets.’

‘How old is she?’

‘Well over ninety.’ He sighed. ‘The home’s really nice, you know. But I still feel desperately guilty about it.’ His eyes grew shiny. ‘With the best will in the world, they can’t let her take more than a tiny fraction of her stuff. She’s going to be so lost without her things. She still has a very sharp mind.’ He rubbed his face. ‘Sometimes I think it’s kinder when the wits go first, although I suppose it isn’t. My mother’s legs have let her down in the last year or so. And her sense of balance isn’t what it was.’

‘Does she know you’ve got me sorting out the house?’

He grimaced. ‘I’m afraid I didn’t have the courage to tell her. She would want to be consulted about every single thing. I mean well, believe me. I know some people think I should wait until she … you know. But she’s never coming back here, so it seems silly to just mothball everything. Besides, we might need to sell up at short notice, although I hope not.’

‘So what’ll you do with it all?’

‘No idea. I’ll make a plan when I know exactly what there is. Nothing’s going to happen soon.’

‘You shouldn’t feel guilty,’ said Thea bracingly, aware that he was deeply unhappy. ‘She’ll have all her comforts there – all her meals provided. Warm. Safe. It must have lots of advantages.’

‘All true,’ he said. ‘And she mostly likes the place. But it’s such a huge change, and old people hate change.’

‘No escaping it, though. There’s nothing you can do about it.’

He gave her a look that startled her. It contained something close to dislike for a moment. Then he blinked and it was gone. ‘It was her own decision. I never pushed her into it. But people will

think

I did. “Packed his old mum off into a home” – that’s what they’ll be saying. They’ll assume I want to get my hands on the house. It’s worth a small fortune, even in this condition. And I don’t have to share it with anyone else.’ The last words carried additional emphasis. Again, they both looked around the room. There were pictures on the wall, a Victorian clock on the mantelpiece, a piece of china that Thea thought could be Moorcroft, on a small table. ‘But all that can wait,’ he finished.

She opted for a change of subject, asking which services were still connected, and which not. ‘No phone,’ he said. ‘But the power’s on, and there’s an immersion heater for hot water. I didn’t think it was worth getting the Aga started, although I’m afraid the kitchen does get cold without it. You can have a log fire in here – there are still some logs in the shed at the back. It’s very effective once it gets going. I hope it won’t feel like an abandoned house that nobody loves.’

‘It doesn’t,’ she assured him. ‘Not with all the furniture still here. You could probably let it out to holiday visitors,’ she mused. ‘They’d keep it alive, so to speak.’ She thought of Drew’s neglected property in Broad Campden, which would feel much colder and more cobwebby than this one.

‘Did you bring any food with you?’ he asked.

‘Not much. Milk, biscuits, tea bags and a couple of things to keep me and the dog going until I can buy something tomorrow. I thought there’d be a shop somewhere nearby.’