Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid (103 page)

Read Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid Online

Authors: Douglas R. Hofstadter

Tags: #Computers, #Art, #Classical, #Symmetry, #Bach; Johann Sebastian, #Individual Artists, #Science, #Science & Technology, #Philosophy, #General, #Metamathematics, #Intelligence (AI) & Semantics, #G'odel; Kurt, #Music, #Logic, #Biography & Autobiography, #Mathematics, #Genres & Styles, #Artificial Intelligence, #Escher; M. C

Nevertheless it is a piece of "reductionistic faith"; it could be considered a "microscopic version" of the Church-Turing Thesis. Below we state it explicitly: CHURCH-TURING THESIS, MICROSCOPIC VERSION: The behavior of the components of a living being can be simulated on a computer. That is, the behavior of any component (typically assumed to be a cell) can be calculated by a FlooP program (i.e., general recursive function) to any desired degree of accuracy, given a sufficiently precise description of the component's internal state and local environment.

This version of the Church-Turing Thesis says that brain processes do not possess any more mystique-even though they possess more levels of organization-than, say, stomach processes. It would be unthinkable in this day and age to suggest that people digest their food, not by ordinary chemical processes, but by a sort of mysterious and magic

"assimilation". This version of the CT-Thesis simply extends this kind of commonsense reasoning to brain processes. In short, it amounts to faith that the brain operates in a way which is, in principle, understandable. It is a piece of reductionist faith.

A corollary to the Microscopic CT-Thesis is this rather terse new macroscopic version:

CHURCH-TURING THESIS, REDUCTIONIST'S VERSION: All brain processes are derived from a computable substrate.

This statement is about the strongest theoretical underpinning one could give in support of the eventual possibility of realizing Artificial Intelligence.

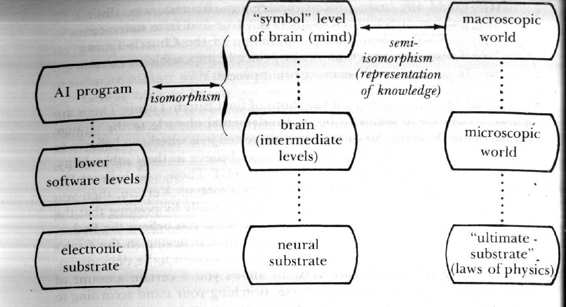

Of course, Artificial Intelligence research is not aimed at simulating neural networks, for it is based on another kind of faith: that probably there are significant features of intelligence which can be floated on top of entirely different sorts of substrates than those of organic brains. Figure 108 shows the presumed relations among Artificial Intelligence, natural intelligence, and the real world.

Parallel Progress in Al and Brain Simulation?

The idea that, if Al is to be achieved, the actual hardware of the brain might one day have to be simulated or duplicated, is, for the present at least, quite an abhorrent thought to many Al workers. Still one wonders, "How finely will we need to copy the brain to achieve Al?" The real answer is probably that it all depends on how many of the features of human consciousness you want to simulate.

FIGURE 108.

Crucial to the endeavor of Artificial Intelligence research is the notion that

the symbolic levels of the mind can be "skimmed off " of their neural substrate and

implemented in other media, such as the electronic substrate of computers. To what depth

the copying of brain must go is at present completely unclear

.

Is an ability to play checkers well a sufficient indicator of intelligence? If so, then Al already exists, since checker-playing programs are of world class. Or is intelligence an ability to integrate functions symbolically, as in a freshman calculus class? If so, then AI already exists, since symbolic integration routines outdo the best people in most cases. Or is intelligence the ability to play chess well? If so, then AI is well on its way, since chess-playing programs can defeat most good amateurs; and the level of artificial chess will probably continue to improve slowly.

Historically, people have been naive about what qualities, if mechanized, would undeniably constitute intelligence. Sometimes it seems as though each new step towards Al, rather than producing something which everyone agrees is real intelligence, merely reveals what real intelligence is not. If intelligence involves learning, creativity, emotional responses, a sense of beauty, a sense of self, then there is a long road ahead, and it may be that these will only be realized when we have totally duplicated a living brain.

Beauty, the Crab, and the Soul

Now what, if anything, does all this have to say about the Crab's virtuoso performance in front of Achilles? There are two issues clouded together here. They are: (1) Could any brain process, under any circumstances, distinguish completely reliably between true and false statements of TNT without being in violation of the Church-Turing Thesis-or is such an act in principle impossible?

(2) Is perception of beauty a brain process?

First of all, in response to (1), if violations of the Church-Turing Thesis are allowed, then there seems to be no fundamental obstacle to the strange events in the Dialogue. So what we are interested in is whether a believer in the Church-Turing Thesis would have to disbelieve in the Crab's ability. Well, it all depends on which version of the CT-Thesis you believe. For example, if you only subscribe to the Public-Processes Version, then you could reconcile the Crab's behavior with it very easily by positing that the Crab's ability is not communicable. Contrariwise, if you believe the Reductionist's Version, you will have a very hard time believing in the Crab's ostensible ability (because of Church's Theorem-soon to be demonstrated). Believing in intermediate versions allows you a certain amount of wishy-washiness on the issue. Of course, switching your stand according to convenience allows you to waffle even more.

It seems appropriate to present a new version of the CT-Thesis, one which is tacitly held by vast numbers of people, and which has been publicly put forth by several authors, in various manners. Some of the more famous ones are: philosophers Hubert Dreyfus, S. Jaki, Mortimer Taube, and J. R. Lucas; the biologist and philosopher Michael Polanyi (a holist par excellence); the distinguished Australian neurophysiologist John Eccles. I am sure there are many other authors who have expressed similar ideas, and countless readers who are sympathetic. I have attempted below to summarize their joint position. I have probably not done full justice to it, but I have tried to convey the flavor as accurately as I can:

CHURCH-TURING THESIS, SOULISTS' VERSION: Some kinds of things which a brain can do can be vaguely approximated on a computer but not most, and certainly not the interesting ones. But anyway, even if they all could, that would still leave the soul to explain, and there is no way that computers have any bearing on that.

This version relates to the tale of the Magnificrab in two ways. In the first place, its adherents would probably consider the tale to be silly and implausible, but-not forbidden in principle. In the second place, they would probably claim that appreciation of qualities such as beauty is one of those properties associated with the elusive soul, and is therefore inherently possible only for humans, not for mere machines.

We will come back to this second point in a moment; but first, while we are on the subject of "soulists", we ought to exhibit this latest version in an even more extreme form, since that is the form to which large numbers of well-educated people subscribe these days:

CHURCH-TURING THESIS, THEODORE ROSZAK VERSION: Computers are

ridiculous. So is science in general.

This view is prevalent among certain people who see in anything smacking of numbers or exactitude a threat to human values. It is too bad that they do not appreciate the depth and complexity and beauty involved in exploring abstract structures such as the human mind, where, indeed, one comes in intimate contact with the ultimate questions of what to be human is.

Getting back to beauty, we were about to consider whether the appreciation of beauty is a brain process, and if so, whether it is imitable by a computer. Those who believe that it is not accounted for by the brain are very unlikely to believe that a computer could possess it. Those who believe it is a brain process again divide up according to which version of the CT-Thesis they believe. A total reductionist would believe that any brain process can in principle be transformed into a computer program; others, however, might feel that beauty is too ill-defined a notion for a computer program ever to assimilate. Perhaps they feel that the appreciation of beauty requires an element of irrationality, and therefore is incompatible with the very fiber of computers.

Irrational and Rational Can Coexist on Different Levels

However, this notion that "irrationality is incompatible with computers" rests on a severe confusion of levels. The mistaken notion stems from the idea that since computers are faultlessly functioning machines, they are therefore bound to be

"logical" on all levels. Yet it is perfectly obvious that a computer can be instructed to print out a sequence of illogical statements-or, for variety's sake, a batch of statements having random truth values. Yet in following such instructions, a computer would not be making any mistakes! On the contrary, it would only be a mistake if the computer printed out something other than the statements it had been instructed to print. This illustrates how faultless functioning on one level may underlie symbol manipulation on a higher level-and the goals of the higher level may be completely unrelated to the propagation of Truth.

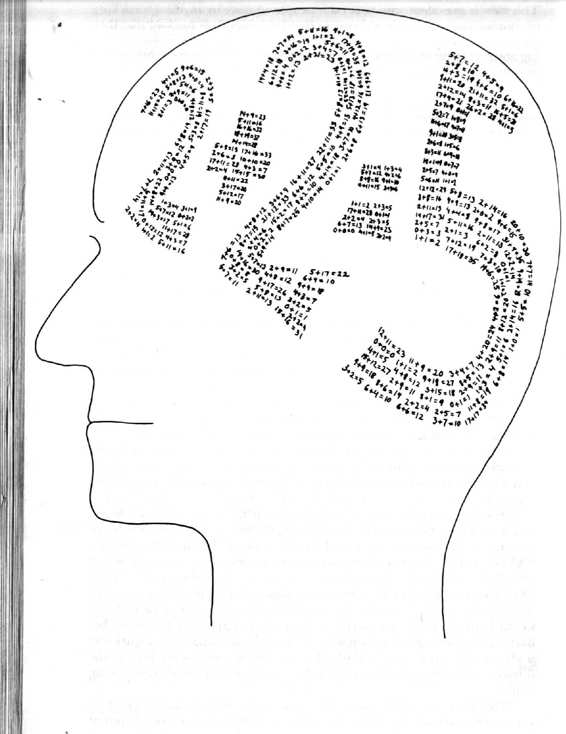

Another way to gain perspective on this is to remember that a brain, too, is a collection of faultlessly functioning elements-neurons. Whenever a neuron's threshold is surpassed by the sum of the incoming signals, BANG!-it fires. It never happens that a neuron forgets its arithmetical knowledge-carelessly adding its inputs and getting a wrong answer. Even when a neuron dies, it continues to function correctly, in the sense that its components continue to obey the laws of mathematics and physics. Yet as we all know, neurons are perfectly capable of supporting high-level behavior that is wrong, on its own level, in the most amazing ways. Figure 109 is meant to illustrate such a clash of levels: an incorrect belief held in the software of a mind, supported by the hardware of a faultlessly functioning brain.

The point-a point which has been made several times earlier in various contexts-is simply that meaning can exist on two or more different levels of a symbol-handling system, and along with meaning, rightness and wrongness can exist on all those levels.

The presence of meaning on a given

FIGURE 109.

The brain is rational; the mind may not be. [Drawing by the author.]

level is determined by whether or- not reality is mirrored in an isomorphic (or looser) fashion on that level. So the fact that neurons always perform correct additions (in fact, much more complex calculations) has no bearing whatsoever on the correctness of the top-level conclusions supported by their machinery. Whether one's top level is engaged in proving koans of Boolean Buddhism or in meditating on theorems of Zer1 Algebra, one's neurons are functioning rationally. By the same token, the high-level symbolic processes which in a brain create the experience of appreciating beauty are perfectly rational on the bottom level, where the faultless functioning is taking place; any irrationality, if there is such, is on the higher level, and is an epiphenomenon-a consequence-of the events on the lower level.

To make the same point in a different way, let us say you are having a hard time making up your mind whether to order a cheeseburger or a pineappleburger. Does this imply that your neurons are also balking, having difficulty deciding whether or not to fire? Of course not. Your hamburger-confusion is a high-level state which fully depends on the efficient firing of thousands of neurons in very organized ways. This is a little ironic, yet it is perfectly obvious when you think about it. Nevertheless, it is probably fair to say that nearly all confusions about minds and computers have their origin in just such elementary level-confusions.