Bronson

Authors: Charles Bronson

I’ve no regrets – only for hurting my beautiful mother, Eira. This book is for Mum – with love and respect.

CHARLES BRONSON

Charlie Bronson would like to thank his many friends, including: Joe Pyle, Roy Shaw, Charlie and Eddie Richardson, Reece Huxford, Simon and Karen, Jan, Andy, Lyn and Chris, Eddie Whicker, Sharon and Steve and Ed Clinton.

Rob Ackroyd thanks his loyal family, and his friends, particularly: Julia, Gerard, Eran, Jane, Graham, Diane, Paul, Olive, Kevin, Janet, and Padraic.

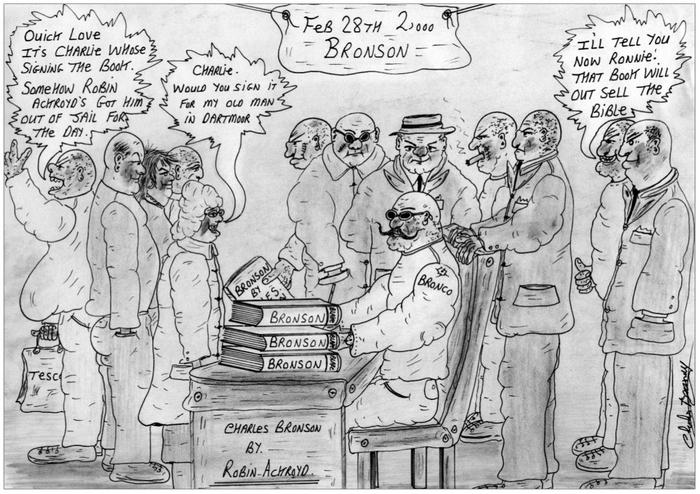

‘I’ll tell you now Ronnie, that book will outsell the Bible.’

Charlie Bronson and I have been friends for many years. My opinion is he would be more benefit to society helping kids than wasting any more time in prison. He has a lot of talent which is going to waste.

God Bless

REG KRAY

There is so much more to Charles Bronson than meets the eye. You may know of him as the strongest man in the prison system, Britain’s Number 1 psycho, or the man responsible for more hostage-takings than any other inmate.

Yes, he has been locked in a cage like the fictional Hannibal Lecter because of his extreme danger. And yes, Lecter-style, he did, infamously, threaten to eat a hostage unless he was given a cup of tea. But the Charlie Bronson I know is a man of great humour and warmth; a talented raconteur and artist. In adversity, a man of real insight.

Charlie is genuinely hilarious. ‘I’m not Hannibal

bloody Hector,’ he says, deliberately mispronouncing the name. ‘He eats people. I’ve never eaten anyone! I’m no more Hannibal Hector than Maggie Thatcher was.’

Charlie is a lost soul, a man from a different age. Ten thousand years ago he would have been the strongest man in the jungle; two thousand years ago, in Roman times, he would have been the unbeaten gladiator; two hundred years ago he would have been a circus strong-man. As I write, he is locked up 23 hours a day in a cell without so much as a window to open, with little natural light, no breeze on his face. His furniture – a chair and table – is made of compressed cardboard. His bed is a concrete plinth with a fire-proof mattress on top. When he is unlocked for his one hour’s exercise, in a razor wire-topped pen, he is accompanied by up to a dozen prison officers, sometimes with dogs and often in riot gear.

Charlie has few visitors. Charlie has been locked up, bar 140 days, for 28 years. Most of that time, almost 24 years, has been spent in solitary. His only creature comforts are a battery-operated radio (he doesn’t watch television) and paper, pens and pencils for his art work. He has, he says, ‘eaten more porridge than Goldilocks and the three bears’. He knows more about the sharp end of prison life than any dozen governors you might nominate. He commands respect from other convicts. Many people fear him; few really know him.

It has been my privilege over recent years to get to know the real Charlie Bronson, to find out what makes him tick, and to work with him on this book. It has not always been easy. He can be very supportive, but also very demanding. I have lost count of the number of lawyers, authors and even members of his own family he has ‘blown out’ over the years. At one point, I would read only the first and last lines of his letters to me, to

gauge his mood, and then put them to one side for a day or two. I really liked the guy, but I could get seriously pissed off with him. I dreaded the words ‘I’m not happy, Robin’ or ‘I’ve got serious mind problems.’

But his humour kept me going. Here’s a little extract from one of his letters:

At times it looked very doubtful I’d ever get out. But recently I’ve become a very understanding guy – more in control. Could be I’m maturing? But it’s probably because I want to get out to get my dick sucked. Well, I’m only human! I may go into films! If that prat Vinnie Jones can do it, why can’t I?

Right. Howz yourself?

Have you met my brief yet? If not … why not! Have you got all the paperwork? If not … why not! How did your sailing trip go? Sea, sun and sex? If not … why not! My last holiday was on the Isle of Wight … but that was only Parkhurst!

And here’s a postscript Charlie added in a letter last summer: ‘Oh! Guess who’s below me? Lifer!

Ex-Broadmoor

! Swallows things. (Sometimes calls you up.) And he speaks highly of you. (Well, he ain’t got much in life.) A very sad case!’

Cheers, pal!

* * *

Charlie knows little about modern life, he has been in jail for so long. He first went inside in 1974, the year that President Nixon resigned over the Watergate scandal. His language is from the ’70s – ‘brill’; ‘wizard’; ‘geezer’. He talks of Doris Day and Shirley Bassey. He has fought the system for more than a quarter of a century.

When I first met Charlie in Britain’s most secure unit – a jail within a jail – he must have shaken my hand half-a-dozen times. Here was a man denied normal human contact. A generous man, who quite simply cannot control his aggression, as he has proved in spectacular style over the years. Not a murderer, but a man who went inside originally for an armed robbery during which no shots were fired. His

seven-year

sentence doubled because he was uncontrollable in jail, and then, in his first brief taste of freedom, he went to work as an unlicensed boxer. Soon he robbed a jeweller’s in his home town of Luton, Bedfordshire. He had lasted just 69 days on the outside.

Sitting opposite me during that first visit was a broad-shouldered man in a green-and-yellow cotton jump-suit, ‘HM Prison’ emblazoned in big black letters on the back. Charlie was smiling,

broken-toothed

, through a fearsome black and grey beard. His head was shaven and his eyes were alight behind his small, oval sunglasses.

We had an hour together. I had gone through the most rigorous security checks to visit Britain’s most violent inmate: police vetting; forms to fill in;

mug-shots

. I was frisked twice at HMP Woodhill, on the outskirts of Milton Keynes in Buckinghamshire. An electronic device was used to take a fingerprint, to ensure I was the same person going in and out. A video-grab of my face was taken for a similar comparison. I went through two metal detectors, like the ones you see at airports, and was checked again with a hand-held detector. My shoes had to be taken off to be X-rayed, the inside of my mouth was checked for contraband, as was my hair and my belt buckle. All my possessions, except loose change, had to be put in a locker.

After walking through air-lock doors, I entered the reception area for visitors, clutching a yellow visiting

slip in a hand which had been stamped with a fluorescent code. There were about a dozen other visitors, including solicitors. None of them was going to ‘House Unit Six’ in the new Close Supervision Centre, a maximum security block well away from ‘normal’ Category A inmates.

‘Oh, a yellow slip?’ said a friendly prison officer. ‘House Unit Six?’ Clearly, not many visitors went there. He looked at the form. ‘Come to see Charlie? We’ll have to escort you.’

I was the first civilian visitor, apart from his solicitor, to see Charles Bronson since he had staged the longest prison siege in living memory, holding an education worker hostage for 44 hours.

Two friendly female warders led me first through barred doors and then across a yard – where, as only Milton Keynes can, there were several life-size concrete sheep on a patch of grass – to the secure block, bounded by razor wire and thick mesh fencing. Down a stark corridor, and under the watchful presence of closed-circuit TV cameras, we finally entered a secure room where I was allowed to use my loose change to buy chocolate bars and fizzy drinks in plastic bottles from two machines. Charlie had signed a form requesting half a dozen bars; I bought eight. The rest of my money was bagged and sealed. I was allowed to take in not a penny, not a scrap of paper – nothing.

And there was Charlie, alone in the brightly lit visiting area – alone apart from six screws and the cameras – pacing up and down like a caged bear.

‘Good to see you! Come on, sit down, over here,’ he urged me.

Time was precious. This was his monthly hour; two visits rolled into one. He was animated, alive. We joked as we sat opposite one another, across a narrow table, on metal seats screwed to the floor. Charlie

crammed chocolate into his mouth as we talked. We were like old friends, pen-pals meeting for the first time. The screws kept their distance.

‘Come on, Charlie,’ I said within a few minutes of us meeting. ‘I don’t believe you’re as tough as they make out! Let’s have an arm wrestle.’ We did, and I lasted barely three seconds, my wrist turning white under the pressure. ‘No one’s ever beaten me,’ growled Charlie.

‘I will one day,’ I told him. ‘Just need a bit of practice.’

‘No,’ he said firmly. ‘No one will ever beat me.’

Towards the end of the visit, he turned sideways on his bolted chair, half-eyeing me out of the corner of his sunglasses. It was as if he wanted to liven the hour by showing me another side.

‘You know, Robin, I’ve got no regrets.’

I heard what he was saying, but I found it hard to believe. Prison is tough and, for Charlie, a lonely existence. The thing is, it is virtually all he knows. One little thing really brought home how stuck in a different age Charlie is. In an almost fatherly way, and showing genuine interest, he asked me what sort of car I drove.

‘Oh, just an old Jetta,’ I said. He looked blank. ‘A VW Jetta,’ I added. ‘You know, a Volkswagen.’ I was getting embarrassed. He was wanting to talk, man to man, about something on the outside – and he was lost. I repeated, ‘A Volkswagen.’

His eyes lit up. ‘Ah! I know! One of them with the engine in the boot!’

I smiled back, reassuringly.

Charlie wrote to me after that visit:

So good to see you after so long! You looked fit and well. I bloody enjoyed it, I really did! My brother Mark looks like you. My other brother

John is out in Australia – lovely man, ex-Royal Marine. Not seen him since 1985, the year I pulled Liverpool Jail roof off! Now, that was a good roof! Summer time … three glorious days up there. I pulled it to bits. Yes, lovely memories! Oh, a terrible beating afterwards. But it was worth it (and the 12 months extra!). A good jail, the old school – not like the nurseries today. The screws were hard, but fair. Some would fight you alone. Nowadays they get a button torn off and they are six months on the sick. How can you respect that?

They are a different breed today (or am I a dinosaur?). Maybe it’s time I got out and put it all behind me. Personally, I enjoyed the good old days – piss-pots, slopping out, porridge six times a week. Now it’s poxy sugar fucking puffs. We rarely get porridge, and when we do it’s not good porridge. Porridge is ‘bird’. Sugar puffs! Do me a favour! Is it real, or what? Next they’ll be whipping us with lettuce leaves! Or hanging us with elastic!

He added, ‘Hey! Did you see the concrete sheep outside the unit? Even Broadmoor ain’t that insane!’

That’s Charles Bronson, and this is his own story, which I hope you will find exciting, sometimes funny and also deeply sad. I hope you will find it ultimately uplifting. After all, Charlie is one of life’s survivors. Has the system created Charles Bronson as much as he has created himself? Does he want to get out, even if he is eventually given the chance? Make up your own mind after reading this book.

Robin Ackroyd