From the Forest (38 page)

Authors: Sara Maitland

The donkey brayed.

The dog barked.

The cat yowled.

And the cock shouted, ‘Cockadoodledoo, doodledo, doo do.’

A hideous cacophony, enough to scare any robbers out of their minds, and these ones rushed out of the house and, as they passed the four comrades, the donkey kicked them and the dog bit them and the cat scratched them and the cockerel pecked their faces, and they ran away through the forest and never dared to come back again.

So the donkey and the dog and the cat and the cockerel decided not to go to the city, but to settle down in this handsome retirement home, grow fat on the robbers’ ill-gotten gains, and live happily ever after, because:

All animals except humans know that the principal business of life is to enjoy it and they do enjoy it.

There are lots of morals to this little fable about gratitude and friendship and making the best of things. I will leave you to work them out for yourself, but remember: The darker the night the brighter the song; the colder the winter the sillier the story, so they say.

11

January

Glenlee

A

wet, raw January, when the dark pounces before 3.30 in the afternoon, does not feel like the time of year for stomping off to walk in the wild woods. It feels more like the time of year for curling up in front of a log fire, watching the flames and slightly dreamily reading fairy stories.

It is also the time of year when I, like all gardeners, occupy myself planning next year’s garden; imagining schemes and ordering plants. So I find myself spending time thinking not so much about forests as about gardens. And thinking about fairy stories and gardens together turns my mind to the nineteenth-century romantic aesthetic in gardening which led to the development of ornamental forests and woods, artificial, but not in the sense that commercial plantation forests are artificial; to the creation of woods of the imagination, the forests of artists and of fairy stories. And I am struck afresh by the synchronicity between the rise of woodland gardens and the re-emergence of fairy stories; this new type of garden emerged, in both Germany and Britain, at almost precisely the same time as the Grimm brothers – speedily followed by other collectors – were first publishing their fairy stories. Indeed, I would argue that they came out of the same cultural movement and influenced each other profoundly. Throughout the nineteenth century people were creating new woods suitable for fairies to live in. They were woods that were meant to look like ancient woods – or, more precisely, like people imagined old woods had looked.

Over Christmas Cathy Agnew, the wife of a very old friend of mine, told me how her husband had taken his small nieces into the wood behind their home, Glenlee, and persuaded them that fairies lived in it and played under a beech tree. So, on a slightly less grim day than many have been recently, I found myself driving over the hill road to Glenlee to explore its wood that is still, at least in the imagination, home to fairies.

Glenlee is a substantial country house built in 1823. It was designed by Robert Lugar, a fashionable and successful architect of the time, who was a leading proponent of the Gothic revival, particularly in Scotland and Wales. Howard Colvin, the architectural historian, comments of Lugar that he ‘was a skilful practitioner of the picturesque, exploiting the fashion for

cottages ornes

and castellated Gothic mansions . . . he was among the first to introduce the picturesque formula into Scotland’.

1

For Lugar, as he himself made clear, the fundamental attraction at Glenlee was its location:

The situation is most agreeably retired, and partakes much of the character of an English park, abounding in well-grown forest-trees, which seclude it, by their density, from the mountain scenery which surrounds it.

The walks up the glen are highly picturesque, and present many beautiful and interesting views, connecting the rich park scene and fertile valley with the distant mountains.

2

‘Agreeably retired’ remains true: Glenlee is a few miles north of New Galloway, a small village at the head of Loch Ken, in the Valley of the Dee. The whole area, known as the Glenkens, is unusually lovely, and ecologically very rich; it is a Ramsar site;

3

the green fertile valley is hemmed in by true ‘wilderness’ – the Galloway Hills to the north and east, and the muscular bulk of Cairnsmore of Carsphairn in the Scaur Hills to the west. The valleys of the Dee and Water of Ken and the long twist of Loch Ken itself create a green corridor between Ayr and Kirkcudbright. Additionally, the Glenkens have extremely romantic associations – most famously, when Young Lochinvar ‘rode out of the west’, he rode down from his home here, to kidnap his bride across the border in northern England.

4

Walter Scott’s poem about him was published in 1808

5

to almost instant acclaim. The area was also much admired by Robert Burns (1759-1796), whose friend John Syme wrote: ‘I can scarcely conceive a scene more terribly romantic . . . Burns thinks so highly of it, that he meditates a description of it in poetry.’

6

So when Lugar came to design Glenlee, its romantic associations were well in place and cannot have failed to inspire his architectural concept.

Although every imaginable approach to Glenlee brings the traveller through wonderful countryside, I probably have the very best of it arriving from the west, along the Queen’s Way – the road through the hills from Newton Stewart. This savagely harsh landscape is where Richard Hannay had his Scottish adventure in

The Thirty-Nine Steps

after he ‘fixed on Galloway as the best place to go’.

7

It is too heavily planted with forestry now, but in places there are great rough sheets of granite so near the surface that even the most optimistic forester never tried to plant there, and there are good views of the Galloway Hills, gaunt and lowering, with the pale winter sunlight catching the remaining snow up on the heights. The wild goats have come down beside the road: they are ‘feral goats’ really, the now wild descendants of the goats that preceded sheep as the common domestic animal of the poor on the high farms in extreme wild places in Scotland. They inhabit the Galloway Hills, like ghosts of a lost way of life.

I find myself thinking about the goats which feature in the fairy stories. There are a good number of them, and they more frequently speak in human language than any other animal except birds. Although adult goats are often tricky and mean tempered and get the protagonists of the fairy stories into trouble of various kinds, baby goats, properly called kids, are always both vulnerable and charming in character. During the nineteenth century the word ‘kid’, which had previously been used to describe a young pugilist or thief, began to be used more generally (though the

OED

still lists it as ‘slang’)

8

to describe human children, usually affectionately. I wonder if that shift in meaning – from pugilist to child, from thief to innocent – was influenced by the very positive role baby goats play in the fairy stories. It is unusual for a word to ‘improve’ its standing; it is much more common – as we have already seen with ‘gossip’ and ‘villain’ – for a word to collect negative rather than positive connotations and associations. But ‘kid’ became affectionate and less critical over exactly the same period that the fairy stories became better known within literate society.

9

Beyond Clatteringshaws Loch, I leave the main road for a very narrow little lane that winds down to the broad valley of the Dee, bypassing New Galloway. The landscape changes abruptly here, the land dropping steeply, although the big hills are still visible to the north. Suddenly it is pastoral; the forestry stops and is replaced by older deciduous woodland of oak, ash and rowan, all bare-branched now, with willow scrub marking the courses of the tumbling burns. This is the Garroch Glen, and it has a secret wild enchantment enhanced by its contrast with the fierce hill country.

10

Here on the steep side of the valley, tucked under the hills above it, is Glenlee. In fact the lane runs behind the house and its park, so I was looking down, through the trees, over the valley. It is still, nearly two hundred years later, very much as Lugar described it: ‘highly picturesque’, with ‘many beautiful and interesting views, connecting the rich park scene and fertile valley with the distant mountains’.

Originally parks had been fairly open wooded areas designed for the preservation and formal hunting of deer; but various factors – including the enclosures, which broke up the necessary large areas with fences, and the improvements to guns, which made game-shooting more pleasurable – meant that this sort of deer hunting declined in popularity from about the beginning of the eighteenth century.

11

At the same time, and partly in response to this, many landowners redeveloped their deer parks as ornamental landscapes, though keeping the old name. The eighteenth-century landscaped parks are now much admired and often seen as elegant barriers against the ‘natural’ woodland that is supposed to have preceded them, an Enlightenment project to demonstrate human authority over nature. It is less known that, as well as keeping the old name, ‘park’, most of the professional landscape designers also kept old trees and woods. They distinguished clearly between gardens, which were heavily reconstructed and managed, and parks, where the plan was to enhance an already existing landscape with a few new features and the rearrangement of longer vistas. Humphry Repton (1752-1818), who wrote extensively on the subject as well as designing landscapes himself, expressed this widespread view:

The man of science and taste will discover beauties in a tree which the others would condemn for its decay . . . Sometimes he will discover an aged thorn or maple at the foot of a venerable oak; these he will respect, not only for their antiquity . . . but knowing that the importance of the oak is comparatively increased by the neighbouring situation of these subordinate objects.

12

These designers saw themselves as developing and improving the traditional deer park: in many cases they even kept the deer as ornamental features. As late as 1867 there were still 325 English parks with deer in them,

13

but while these animals were culled for the table, they were not hunted. The ‘gentlemanly’ way to kill deer became going to the Highlands to stalk and shoot them.

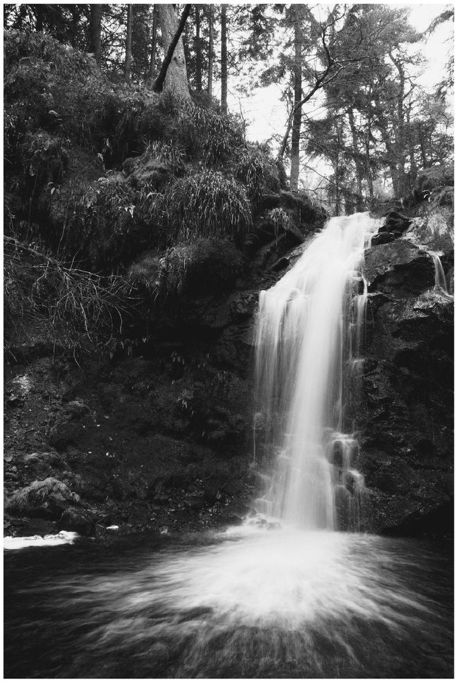

Throughout the eighteenth century the ornamental park grew in popularity – and increasingly included an admiration for woods and glades. At first this was predominantly governed by classical ideas and inspired by the fantasy landscapes of painters like the Poussins and Claude Lorraine; fine examples of this style can still be seen at Stourhead and Stowe, where carefully moulded landscapes, including trees and copses, are decorated with reproduction classical temples, columns and statuary. By the end of the eighteenth century, however, the rise of Romanticism caused a major shift in aesthetic fashion. There was a new delight in the ‘sublime’ and the so-called wild – waterfalls took over from formal cascades; craggy rocks from classical statuary; and ‘wildernesses’ from more formal arrangements of vistas and planting designs. In Jane Austen’s novels the steady progress of the popularity of wildernesses can be observed. In

Northanger Abbey

,

14

written in the late 1790s, Henry Tilney, representing new and refined sensibility, is just laying out a wilderness in the grounds of his vicarage; by 1813, when

Pride and Prejudice

was published, even the old-fashioned and pompous Lady Catherine de Bourgh condescends to sit in the Bennets’ ‘prettyish kind of a little wilderness on one side of [the] lawn’. In the period between the two novels, fashion had moved forward. Among other signs of the times, the Grimm brothers’ collection had been published in Germany.

The marked rise in prosperity and land ownership of the middle and professional class also led to smaller areas of park or garden. You need a great many open acres and a very great deal of money (not just for the installation, but to maintain the park as a sweep of non-economically productive ground) to make a good Capability Brown landscape; you need far fewer to make a grove, a dell, a little wilderness or an ‘ancient’ wood.

By the second half of the nineteenth century a different fashion had a rather strange effect on some of this supposedly ‘natural’ gardened woodland. The Victorians developed a passion for ‘exotics’ – plants that were not indigenous, but had been discovered in far-off corners of the Empire and elsewhere by adventurous explorers. The range of available trees and shrubs suddenly expanded radically – and among the new plants were many well suited to the new natural or woodland gardens. It turned out that a number of these did very well in Britain.

15

A large variety of new conifers was introduced – Wellingtonias, noble fir, sequoia, monkey puzzles – as well as other dark-leafed species, like copper beech, which seemed to suit the mysterious atmosphere the planters wished to develop.