From the Forest (42 page)

Authors: Sara Maitland

‘Go back to bed,’ she says and he walks obediently to the door, then stops. He turns again to look at her, crouched in her corner, and suddenly she says, ‘Yes, you should have married me.’

‘I was afraid,’ he says slowly. ‘I was afraid of you. You knew who I was, you always knew. You were afraid of me. You were right to be afraid. I wasn’t good enough; I was just an old soldier with no right to marry the real princess. I was afraid of loving you and betraying you and hurting you.’

‘Well,’ she says without bitterness, ‘we got that wrong, didn’t we?’

She does not say, ‘I love you.’ She does not need to.

He leaves the dormitory and walks a short way up the stone-flagged corridor. Then realises he has left his little cloak behind. He stands still for a moment, turning the pretty, ruined dancing slipper in his hand. He goes back. She is still sitting up on her bed. He crosses the room and picks up the cloak. He puts it on, vanishes, takes it off, reappears and grins at her.

Suddenly she laughs, a sweet birdlike sound; like a robin in the winter forest.

Slowly he says, ‘If it isn’t real . . . that forest, that palace, those princes . . . if it isn’t real, then perhaps we could go dancing with the others. Just sometimes. Just for fun. I could wear this cloak and no one would ever know. If it isn’t real, if it’s just a fairy story.’

‘Yes,’ she says, ‘yes, that would be fun.’ She laughs again and he laughs too.

12

February

Knockman Wood

F

ebruary is the bottom of the year, the dead time. The winter has scoured the land; it looks naked and clean. The dark still comes early and the nights are long and cold.

Although, for once, it is not raining, there is a sharp wet wind carrying mist and mizzle, raw on my face; there was a frost last night and there is still a skim of ice on the edges of puddles and ruts; I am glad of gloves, woolly hat and gaiters. I am stomping across a small bleak plain which was once wood pasture; there are still some fine old oaks, a few ashes with their hard black buds like spearheads, and some scrubby hawthorn; away to the east there are even some cows pasturing. But there are more tree stumps, more dead bracken and more reedy bog than there should be and the trees are now far too widely spaced. In summer this is a gloriously rich habitat full of wild flowers and butterflies, but now it is grey and depressing. The track is waterlogged, and to compensate, other walkers have, in places, diverged from it and cut new waterlogged little paths, a wider and wider smear of mud alongside the main track. It is all pretty bleak.

One reason it feels bleak is that this is a woodland habitat lost more to neglect, to underuse, than to aggressive deforestation or enclosure. In that sense it perfectly illustrates the symbiotic relationship between forests and people. If you overgraze open woodland the bracken gets in; once that has established itself you no longer have useable wood pasture because neither sheep nor cows eat bracken, unless desperate. Bracken, that perfectly natural ‘wild’ plant, is the enemy of woodland: once established, bracken takes over aggressively, reducing the amount of sunlight reaching the earth and preventing flowers and seedling trees from germinating and developing, reducing biodiversity and renewal – and it is extremely difficult to get out. Bracken, in this sense, is like deer; without management, they will both destroy woodland and prevent its regeneration. Our relationship with the woodlands is so ancient and so complex that we cannot go back to the beginning again – the conditions of ‘the beginning’ no longer exist.

Of course, one of the advantages of walking in February is that there are no nettles, and not much visible bracken either. Gently the plain begins to rise, and so does my mood. Along the slope ahead of me there is the loveliest high, undulating dry stone wall. Even at first sight there is something strange about this wall; it curves graciously like a wave, not following any natural line or geological feature. It is too beautiful, too well made and far too tall to be an ordinary farm dyke. And it is not – it was constructed in 1824 as the boundary to a deer park. In a moment of sublime romanticism the then owner not only made a brand new deer park, he stocked it with fallow deer, not native to these parts. Not ordinary fallow deer either, for some of them were white. Some of them still are. I have seen white deer in the woods beyond the wall. Each time I see one, despite knowing they are ‘artificial’, I am re-enchanted – they seem so much the creatures of dreams, of medieval romance and of fairy stories. In several stories deer, often magical, lead princes to their true loves. In ‘Brother and Sister’ the children run away from their cruel stepmother and get lost in the forest, where the boy is transformed into a deer – although he can still speak. Later they find a little house and live there, with the sister taking tender care of her deer-brother. A royal hunt comes to the forest and the deer-boy cannot resist his impulse to join in the sport.

1

He is hunted and wounded by the King, who then follows him to the cottage and falls in love with the sister. They go to the King’s palace and eventually, despite further machinations from the stepmother, the spell is broken and the boy restored. I love this story, partly because there is an unusual gentleness in the bond between the siblings. The girl cares for him very tenderly:

Every morning she went out and gathered roots, berries and nuts for herself, and for the fawn she brought back tender grass, which he ate out of her hand. This made him content and he would romp around her in a playful fashion. At night when the sister was tired and had said her prayers, she would lay her head on the back of the fawn. That was her pillow, and she would fall into a sweet sleep.

It is as though the bossy busy big sister needs the little brother in an animal form before she can express her true affection – no other pair of siblings in the tales, and there are lots of them, demonstrate this intimate physical affection.

2

I am not looking for deer today.

I am going in search of Sleeping Beauty’s castle.

As it happens, I know where it is, unlike the first time, when I found it entirely by chance. On the Ordnance Survey map it is called Garlies Castle; it was built in 1500 on the site of an even older castle and abandoned in the early nineteenth century. But on a raw February day, in the quiet of the winter forest, it is Sleeping Beauty’s palace. It is deep in the woods above me, and they are perfect woods for the story. They are ancient oak wood inter-planted in the early nineteenth century with beeches. The same owner who built the wall inserted these grander trees around his ruined castle and all along the southern boundary of his deer park, where they could be viewed from the new house he built to replace the castle. Now their fine-fingered winter twigs and massive grey trunks are just passing maturity and make a wonderful visual contrast to the oaks.

3

Garlies Castle is at the northern end of the Knockman Wood, a stretch of ancient woodland which demonstrates a surprising number of the features of forest history that I have been exploring and at the same time is also part of a project which offers some vision of a way forward for our ancient forests.

The Knockman Wood is in the Cree Valley, a small river system that drains off the high Galloway Hills. Either side of the river, and particularly on its eastern bank, the land rises sharply into open moor and high hills Although the area was inhabited from the prehistoric period, it was never sufficiently fertile to justify the effort of clearing the valley sides of trees above the water meadows. A wet climate, little agricultural disturbance, steep slopes and an acidic soil is the perfect terrain for oak forest, and the Cree Valley maintained a significant amount of semi-natural forest for an unusually long time.

But in the twentieth century Galloway, as I have already mentioned, became one of the areas of the country most heavily affected by the development of plantation forestry. Nonetheless, for an assortment of reasons – the terrain was too rough, steep or wet; the woods were particularly remarkable or historic; just on the whim of individual landowners – small patches of ancient wood escaped the ‘locust years’. These smaller woods were often adjacent to or even within the plantation forest, awkward little parcels of loveliness. Inevitably such a patchwork has a range of owners and contains some oddities,

4

but presently all of them are managed by the Cree Valley Community Woodlands Trust (CVCWT), whose aim is to ‘develop a Forest Habitat Network that has at its core the River Cree, with riparian corridors . . . from source to sea’.

5

The jewel in its crown is the glorious Buchan Wood higher up at Loch Trool, a fragment that, like Staverton and Ballochbuie, is as near as we have to untouched natural woodland.

6

The CVCWT owns none of these woods, it just manages them. In the fairy stories we have seen that it is the people who work in the forests, not the distant kings who own them, who turn out to be the ‘good’ characters; so this feels like a promising omen.

There is a lot to be said for both ‘local’ and ‘partnership’ in this context. It is a model that works. In Finland, which not only has the most forest (as a percentage of land area) in Europe, but is also increasing its forestry faster, there is a partnership between the government and very local owners. In 1947 Finland nationalised all its forests and the government then redistributed them to the adjacent farms: 35% of Finland’s forests are owned by local farmers who work them together with their traditional agricultural land. This has not only made the forests better and more sustainably managed, it has kept rural farming viable and thus maintained the rural population.

7

I begin to feel more hopeful, despite the bleak weather and the sense that winter still has a long time to go. I am cheered too by the knowledge that organisations like the CVCWT have followed the lead of the national Woodland Trust and are bringing our woods under more loving care. I know I am not alone in feeling a small measure of optimism. Rackham has commented that in the 1970s he felt that old British forests were doomed, but more recently there has been a true shift of consciousness:

Those who expect me to predict the next 40 years should ask whether in 1966 anyone could have predicted the state of woodland by 2006. Forty years ago there seemed no future in natural woodland. Who would have predicted that a goodly number of ancient woods would still be there in the twenty-first century, that plantation forestry would lose [its] economic base . . . that the Forestry Commission would be leading the way in recovering replanted woods and that the idea of new National Forests presented as imitating natural woodlands would attract huge popular support?

8

Perhaps that will prove true for the fairy stories too.

At the top of the slope I come to a gate in the deer park wall; close to, the wall seems even more magnificent than from a distance; it is taller than me and both elegant and sturdy. Beyond the gate there is a wide slope of rough grass and bracken, but I follow a little track, grassy and clean, across it, toward the edge of the trees. Just before I walk into their embrace, I look round, down across the plain I have just climbed and then beyond to the bigger hills whose tops are sparkling with snow. I become aware then that the light is lifting and the sky clearing. And as soon as I slip between the first trees I am out of the wind; I can still hear it in the canopy, but on the ground it feels sheltered and hushed. These are old oaks and the ground is vivid with green moss. The path winds a little to avoid the trees. I may be searching for Sleeping Beauty’s castle, but I am walking Red Riding Hood’s path: I am not much tempted to wander from it; it feels just wintery enough to remind me to be glad that there are no longer any wolves and I am quite safe. There are no other people in the wood today, which adds to the sense of being in a magical place.

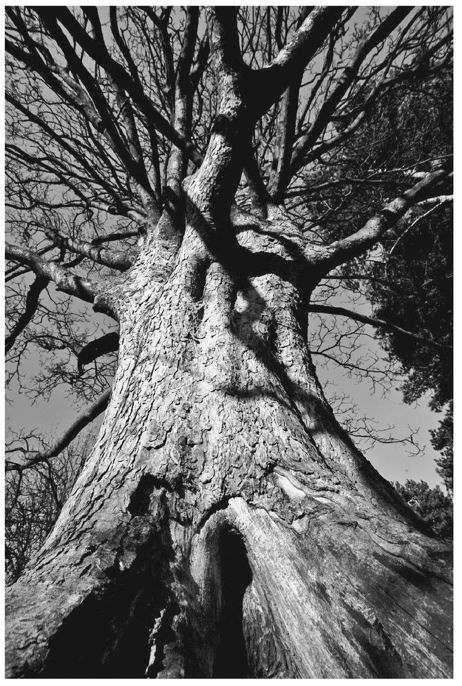

The path rises along the flank of a fairly steep hill – here and there I can see out to the fields and other woods, but mainly I am enclosed by the rough oak trunks and the ups and downs of the topography. There is a bright and busy burn which has cut its way down into a rocky gully, where in summer ferns and wild flowers scramble, along with briars and nettles and blackberries. The gully has almost vertical sides, and suddenly above me I feel a change of light and look up and there is a ridge with a line of huge silvery smooth trunks holding feathery twigs and horizontal branches right overhead; I cross the burn and scramble up the track, which is running with water itself, almost a stream, rocky and muddy. Because I need to watch my feet, I come very suddenly to the top. The ground levels off in front of me, creating a little artificial platform with the ground dropping away sharply. And here on this level space, the trees crowding around it, edging closer, hiding it protectively from view and disturbance, and at the same time, slowly and inexorably destroying it, is Sleeping Beauty’s castle.