From the Forest (33 page)

Authors: Sara Maitland

But by far the most common talking animals are woodland creatures who just happen to talk. Although very occasionally, as in ‘The White Snake’,

14

the humans have to learn how to understand their language, more often they just speak normally and nearly always helpfully. All sorts of animals have this skill (if that is the right word) – it is an integral part of the magic of the forests and of the stories themselves. There are talking frogs, wolves, ants, foxes, snakes, goats, horses, cats, deer and, above all, birds – of many different species. Nothing else seems to distinguish them from their non-talking relatives, except that they are treated with respect and gratitude by the wise hero or heroine. One of the stranger realities here is that there is no indication that all animals can talk; for instance, no human character hesitates to kill for food or self-protection. In ‘The White Snake’ the hero happily hacks the head off his own (non-speaking) horse to provide a meal for some (talking) raven fledglings; huntsmen go on hunting after talking with a deer or fox; no one is a vegetarian. It is simply that some individual animals can talk and they will always say something worth hearing.

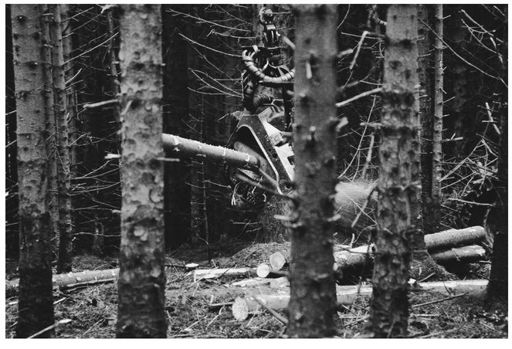

I have no convincing explanation for this insistent narrative device, and I have never read anyone who comments on it. But watching Max McLaughlin’s dog in the highly manipulated ‘continuous cover’ glade – where first the forest itself was artificially inserted into the landscape and now it is being deliberately (and mechanically) managed to look more ‘natural’, more like the forests of childhood and memory, more like an invented ideal of ancient woodland – I was provoked into questioning the interplay between the imagination and the real, between the forests and the fairy stories, and how that relationship changes. Who are the ‘good’ and ‘bad’ characters, and how do we tell? What is animal and natural; what is cultural and human? What is magical? What is imaginary? Everything happens in the forests.

Continuous cover is still a new and experimental approach to forestry, not just in the UK but elsewhere too – and, like any experiment with trees, it will take a very long time to find out if it is going to be successful. But it is also a move back to how forests were managed before modernity, when trees were coppiced or pollarded or left as maidens and then cut individually for timber, when wild and domestic animals were less clearly distinguished, when the line between work and leisure was blurred, and the idea that you grew trees for both ‘pleasure and profit’ did not need to be argued.

Meanwhile, across the rest of the forest, old-style (which is a very new style) commercial forestry continues, with clear-felling and replanting, and in some places clear-felling that will not be replanted but left to regenerate on its own. In the centre of the forest there is a large, long lake, Kielder Water, which is in truth a reservoir – as artificial as the forest – with boats for hire; there are camping sites; miles of forest track – for riding and off-road cycling and walking, and which include a section of the Pennine Way; a very beautiful new observatory equipped with a large telescope, and also space to use your own. There are some pieces of environmental art scattered encouragingly around; there is a castle and a village with a pub. It is all somewhat confusing – is this forest? Is this a taste of the wild? Is it in fact nothing more than a rather crude theme park intent on making a profit? Is it the best chance we have of preserving into the future some remnant of our forest roots? I do not know the answers here, but it makes me feel intrigued and hopeful to see the Forestry Commission wrestle with them.

In an unexpected way, although the trees and other natural phenomena themselves have little or no resemblance to the forests of the fairy stories,

culturally

Kielder is perhaps more like the medieval forest than the precious and beautiful little pockets of remaining ancient woodland are. A forest like Kielder is a profoundly social place as well as a wild one. In the fairy stories there is always a lot going on in the forests. People work there: the stories are full of characters busy about making their livelihoods – not just in the obvious task of wood cutting, but also mining, hunting, animal tending and farming. In the fictional forests, too, there are villages and castles. There is also a great deal of leisure in the woods of fairytales – meetings and eating and socialising of various kinds, like hunting, not only for food, but also for amusement. There are fairs, and evenings by campfires and chance encounters, and a considerable amount of social play. There is learning in the forests – they serve a true educational function: foolish young people go out into the woods and come back wiser, often through positive encounters with trees, flowers, animals, birds, or humans.

The forests of fairy stories are large but, apparently, well populated. There are permanent residents: witches in gingerbread houses, robbers in dens, woodcutters at work, millers in their mills, farmers in their fields, landowners (usually kings) in their castles with their domestic servants and their families around them, and peasants trying to survive. And over and over again, there are travellers, people who do not live or have their business among the trees but who are passing through on their own quests and journeys – on foot, on horseback or in carriages of various descriptions. On the one hand the forest can be very large and lonely; Hansel and Gretel and Snow White are all lost and alone for a while in the forest – but then they all meet strangers, living and busy deep in the woods. The sister in ‘The Seven Swans’ settles like a bird into a tree to live out her vow of silence – and almost immediately a hunting party comes by; Little Red Riding Hood barely has time to reach her grandmother’s house when a woodcutter passes by. All weddings are well attended; all inns are full of company; and if you want to christen your baby daughter, there are at least thirteen wise women living near enough to invite.

There is another fairy-story aspect to Kielder: the road goes right through the middle of it. In other large forests, like the New Forest and the Forest of Dean, there are roads of course, but they usually amble from one village to the next, with the forest broken up by farms and houses. The roads do not enter the forest on one side and go right across it for over thirty miles almost without any break in the solid wall of dark trees on either side and only a few places open enough to see the hills above the forest or the lake at its foot. You leave the wide hill country at Bellingham in the East, set off up the valley of the North Tyne, still small and gurgling over stones, and then it is all forest until you emerge into wide hill country at Riccarton in the West. If you were to drive past Kielder village in the night, you would see the twinkling lights through the trees as the travellers in the fairy stories do. It is a proper journey; once you have passed the dam at the bottom of the lake there are extremely few houses, no shops and no petrol stations on the road until you get to the other end. Off the road there are little rough tracks and paths which lead deep into the forest and eventually out onto the high moors above, but in this respect Kielder replicates the endless travels through the forests of fairytales, the road along which the heroes and heroines go out to seek their fortunes and find their adventures.

I made that journey myself the next day, heading west towards home. The castle, itself an eighteenth-century fake built as a hunting lodge, stood up above the little village, constructed for the original forestry workers (before the village was built they lived in a camp now drowned under the reservoir). The road wound through the trees, up towards the Scottish border and then down into the Liddel Valley. There were miles and miles of unbroken forestry here, enough to be impressive. In 2006, Oliver Rackham wrote:

Forty years on, was it wise to object so strongly to blanket afforestation? Ought plantations to be scattered over the country, rather than concentrated in a few areas? Blanket afforestation intrudes on fewer views than pepper pot afforestation; it affords economies of scale for the foresters; and it allows plantation ecosystems – whatever they might be – to develop on a large scale and with a wider range of habitats and of possible sources of animals and plants.

15

Like Rackham, in actual experience I found the enormous reach of Kielder much less intrusive that the frequent little blobs of forestry scattered around the Scottish hillsides. Driving across the open hills to the west, I started to think that all the forests in all the fairy stories are artificial: they are idealised fantasy forests in which strange things can happen and lives can be changed.

Little Red Riding Hood and the Big Bad Wolf

Once upon a time there was a man who lived alone in the forest.

He lived in the forest in a small cottage a long way up a rough track. He worked in the forest, tree felling, track filling, ditch digging, and deer killing. Power saw and rifle. On the whole he worked alone, although if there were tasks to be done requiring more than one worker, he would do his share, silently and without smiling.

Once a week or so he came down his rough track on his quad bike and went to the office to get his work schedule. He broadly followed his orders; no one could quite say that he did not do his job. His boss and his colleagues were uncomfortable around him. There was a faint shadow that fell when he arrived and that evaporated in the sunshine of his departure. They did not like him, but they never teased or bullied him. He was strange and dangerous.

Once a month or so he came down his rough track in his Land Rover and went into the village and bought supplies. Tea bags, powdered milk, sugar, probably more biscuits and less fruit and vegetables than was good for him. He never bought meat, but then most of them didn’t – why pay for what you can kill for free? He looked at his feet, never received any post, and spoke to no one.

Once a year he would bring his quad and his Land Rover in for servicing. He would draw his equipment from the store as and when needed, never asking for any favours, never taking less than his due. In the winter the smoke from his stove could sometimes be seen drifting up from among the trees. Occasionally, especially when it was misty or very cold, someone would say in the pub of an evening that he had taken to coming out at night, prowling, spying; but someone else would tell the first someone not to be so bloody stupid and the conversation would drift off again somewhere else. No one really cared enough to give a sharp, eager edge to the gossip. He was not originally from round there anyway.

Once, maybe three years back, he had not come to the meeting and he had not been to the village. People noticed. They always do. After a week or so Ken and Davie were sent to check on him. They rode up, roaring their quads, partly delighting in the day off, partly irritated, partly curious and, although they would never have admitted it, partly scared. The cottage looked dark and shabby. They shouted a bit outside and finally bashed on the door. He came out looking dreadful, obviously ill, probably feverish; but he had his rifle in his hand and he cursed them, so they fled. Embarrassed by their fear, they told the office he was sick but did not want any help. The next week he arrived at the meeting on time but he did not thank the boys or the foreman.

It was a life.

He lived alone because he liked his own company and disliked the company of other people. He felt safe in the huge emptiness of the forest and its muttered comings and goings. He was at home in the wildness of it, the secrecy. Other people broke into those secrets and into the dark places in his guts. They gave him a fierce headache, which was hatred, although he did not know that.

One night, late – almost midnight – in winter, with snow on the ground and a moon four or five days off the full, silvering the edges of heavy, fast-flying clouds, his phone rang. It was the emergency call – three rings, then silence, then another three rings and silence. After four rounds of that he answered the phone, grunting his name. Could he get down quick? There was a lost child. The voice was almost apologetic. It was Iain’s stag night and so most of the boys were away and probably drunk and hard to get hold of. The voice did not quite say they were sorry they had to bother him but it was implicit, hanging there in the frowsty cottage air.

He dressed quickly, took his torch, his rifle, heavy boots, gloves, gaiters, balaclava. First aid kit. Keys to the gates. It was part of the job, although he had never had to do it before. When he went outside the cold caught his throat and he coughed; then, standing still in the dark, he heard a high-pitched scream. It was not a child; it was a rabbit, taken probably by a fox. He knew it was important that he got down as quickly as possible, before anyone started wondering where he was, but even in his haste he noticed the neat double footprints of the roe deer along the snow on the track. He preferred roe to the occasional big red deer that came down from the high moor; he liked the way their heart shaped rumps flashed through the trees as they leapt away. Their meat was sweeter and easier to manage too.