Catholic to indulge in overt racial antiSemitism. Moreover, the two wings of the movement were badly split over the issue of Anschluss with Germany; the panGerman Styrian Heimatschutz was in favor of the union, but the Catholic wing, which was closely associated with the Christian Social Party, was opposed, especially after Hitler's takeover in 1933.

|

Complicating the issue of antiSemitism still further was the much needed financial support of some Jewish bankers such as Rudolf Sieghart, Jewish industrialists like Fritz Mandl, and the predominantly Jewish Phönix Insurance Company, which sympathized with the Heimwehr's staunch antiMarxism. Richard Steidle, who came from the ultra-Catholic province of Tyrol and was the Heimwehr's coleader from 1928 to 1930, said the movement was not anti-Semitic, but merely opposed to Jewish Marxists and destructive Ostjuden. Patriotic Jews, Steidle said, were welcome comrades against Marxism.

5

|

If the attitude toward Jews was somewhat ambiguous, the attitude of at least the more politically conservative Jews toward the Heimwehr was also equivocal.

Die Wahrheit

, the mouthpiece for upper-middle-class assimilated Jews, wrote in October 1929 that "Austrian Jews" approved of the Heimwehr's opposition to the high taxes imposed by Vienna's Socialist government. Jews also favored the Heimwehr's demand for strict proportional representation in Parliament, according to the paper. It is also true that some Jewish businessmen gave in to Heimwehr demands to dismiss their Social Democratic employees, thus doubtless increasing antiSemitism in the working class. Moreover, according to the Heimwehr's most recent historian, not a few Jews actually joined the Heimwehr, although none of them ever became leaders.

6

|

The tolerant attitude that some Jews held toward the Heimwehr began to change in 1930 as the Heimwehr became more outspokenly anti-Semitic. In October, Dr. Franz Hueber, a minister of justice in the federal government and brother-in-law of Hermann Göring, announced that Austria "ought to be freed from this alien [Jewish] body." As a minister he "could not recommend that the Jews be hanged, that their windows be smashed, or that their shop display windows be looted. . . . But we demand that racially impure elements be removed from the public life of Austria." Not surprisingly, Jewish members of the Heimwehr began resigning about this time and by 1934 the organization was no longer accepting Jews as members.

7

|

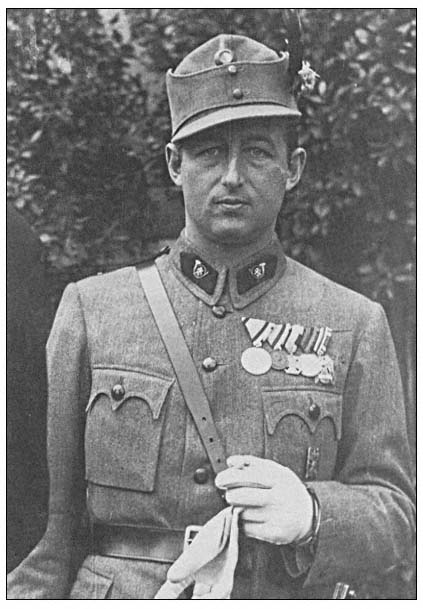

In the ideological middle of the Austrian Heimwehr, trying to balance its panGerman and racist wing with its Catholic-conservative branch, was its leader for most of the period between 1930 and 1936, Prince Ernst Rüdiger Starhemberg. Like the organization as a whole, he was caught between the need to appease the Heimwehr's Jewish financiers and his desire to maintain

|

|