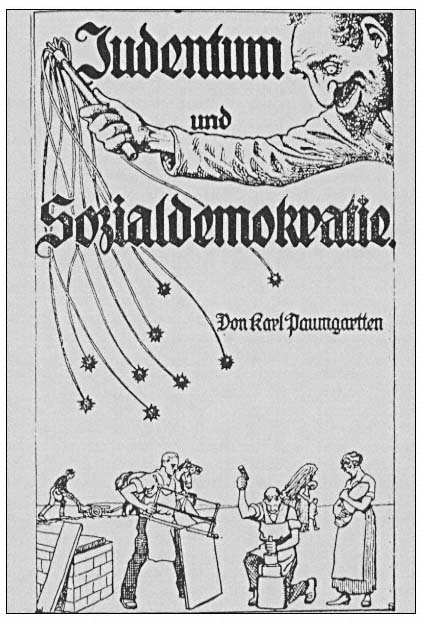

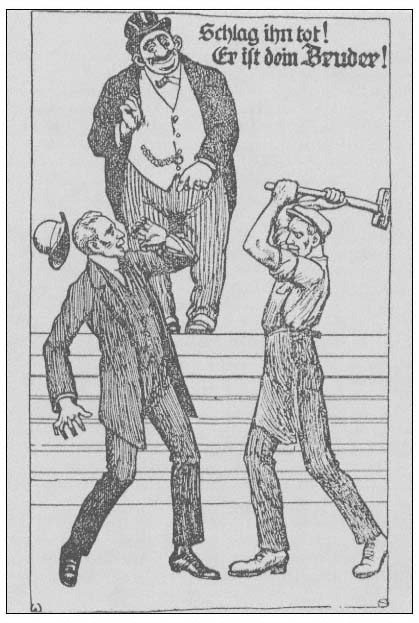

Roman Catholic antiSemitism was also far more diffuse than the Marxist variety. Marxists limited their attacks to Jewish capitalists and, to a much smaller extent, the Zionists. Catholics sometimes also attacked "Jewish capitalism" as well as "Jewish materialism" and, in theory at least, agreed with Socialists in rejecting racial antiSemitism. But by far their greatest wrath was reserved for the Jewish intellectuals, especially those in the Social Democratic Party. The secularism and modernity of these Jewish savants were in direct conflict with the religious traditionalism of Catholics. In premodern times practicing Jews had been the chief objects of Christian antiSemitism; however, after the mid-nineteenth century, the Catholic church, not only in Austria but also in Poland and other European countries, saw "freethinkers"whether or not they still belonged to the Jewish community, had nominally converted to Christianity, or had renounced religion altogetheras by far its greatest threat. Such Jews were held responsible for all the trends of modern society that Catholics abhorred: atheism, Bolshevism, revolution, liberalism, capitalism, and pornography. On the other hand, as we already saw with the Zionist Congress of 1925, Austrian Catholics assumed a fairly benevolent attitude toward Zionism. Likewise, Catholics did not object to Orthodox Judaism, no doubt because Orthodox Jews, even more than Zionists, tended to live in a world of their own and posed no threat to the Catholic religion or to traditional Christian values.

1

|