Financial Shenanigans: How to Detect Accounting Gimmicks & Fraud in Financial Reports, 3rd Edition (27 page)

Authors: Howard Schilit,Jeremy Perler

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Accounting & Finance, #Nonfiction, #Reference, #Mathematics, #Management

Fannie got into trouble for disregarding hedge accounting rules by valuing and categorizing its hedges inappropriately. In a nutshell, Fannie did not record declines in the value of its derivatives appropriately; it classified some hedges as effective (no impact on earnings) when they should have been treated as ineffective (impact on earnings). This trick allowed Fannie to continue its smooth earnings by giving management the discretion to take gains and losses on derivatives in whatever period it saw fit. Most of Fannie Mae’s $6.3 billion aggregate restatement was the result of its improper hedge accounting. In fact, Fannie’s unreported derivative losses totaled $7.9 billion.

Accounting Capsule: Accounting for Derivatives

under SFAS No. 133

Derivatives are financial instruments whose value is derived from changes in some economic variable. For example, a stock option on Wal-Mart gives the owner the option to buy a share of Wal-Mart at a fixed price. The value of that stock option is derived from changes in the value of Wal-Mart’s stock price.

In addition to options, many different types of derivatives exist, including futures contracts, forwards, swaps, and collateralized debt obligations, to name a few. Innovative financial engineers (some would call them “Dr. Frankensteins”) continue to churn out complicated new derivative instruments to this day.

Accounting rules (SFAS 133) require that derivatives be marked to market each quarter. The mark-to-market adjustment (i.e., the change in fair value) is generally reported as earnings (or loss) in the current period, unless the derivative is being used as an effective cash flow hedge on a future transaction . If a derivative is being used to hedge an asset or a liability effectively, the value of the hedge will move in the opposite direction from the value of the asset or liability. As a result, quarterly fluctuations in fair value on certain types of effective hedges do not affect earnings.

GE Abuses Derivative Accounting to Keep Its Earnings Streak Alive.

Like many large companies, General Electric (GE) issues commercial paper, a form of very short-term debt with variable interest rates. To hedge against exposure to changing interest rates, GE entered into derivatives called interest-rate swaps (so called because GE is “swapping” its variable interest-payment obligation for a fixed payment obligation). If they are done appropriately, interest-rate swaps on commercial paper qualify as effective hedges under SFAS 133 (as discussed previously), which means that earnings would be unaffected by volatility in the value of these derivatives.

A problem arose in late 2002 when GE seemed to have “overhedged,” or entered into more swaps than it needed to hedge its commercial paper interest-rate risk. Naturally, the amount that GE overhedged should be considered ineffective under SFAS 133, which means that the quarterly changes in value should affect earnings. (These hedges were ineffective because they did not offset anything.) GE quickly realized that it would be required to record a pretax charge of $200 million as a result of these ineffective hedges.

Throughout the December 2002 quarter, GE scrambled to find a way to avoid recording this $200 million charge. In early January 2003, after the quarter closed and just days before the company reported earnings, GE created an entirely new accounting approach for these hedges that provided the desired results. The auditors signed off, and GE kept its streak of meeting Wall Street estimates alive. One not-so-small matter remained: the new approach was in violation of GAAP. Several years later, the SEC busted GE for accounting fraud.

Watch for Large Gains from Ineffective Hedging

. Investors should be cautious when a company reports large gains from hedging activities, as these ineffective (sometimes called economic) “hedges” may really be unreliable speculative trading activities that could just as easily produce large losses in future periods. In addition, investors should look out for ineffective hedges that produce gains well in excess of the loss in the underlying asset or liability.

Consider Washington Mutual Inc., with its history of presenting large gains on activities that it characterized as hedging. In 2004, the company reported $1.6 billion in gains that were classified as “economic hedges” against a $500 million loss from its unhedged MSR (mortgage servicing rights) asset. In other words, Washington Mutual’s hedging activities resulted in gains that were three times the size of the underlying loss. Investors should also be wary of “hedges” that move in the same direction as the underlying asset or liability, as this may signal that management is using derivatives to

speculate

, not to hedge.

3. Creating Reserves in Conjunction with an Acquisition and Releasing Them into Income in a Later Period

As we have pointed out previously, acquisitive companies create some of the biggest challenges for investors. For one thing, the combined companies immediately become more difficult to analyze on an apples-to-apples basis. Second, as we explore in Part 3, “Cash Flow Shenanigans,” acquisition accounting rules create distortions in the presentation of cash flow from operations. And finally, companies that are making acquisitions might be tempted to have the target company hold back some revenue that was earned before the deal closes so that the acquirer can record it in the later period. That is where our next story begins.

How to Make a New Friend Very Happy

Imagine that you recently signed an agreement to sell your business, with the closing to be in two months. You also receive instructions to refrain from recording any more revenue until the merger is consummated. Somewhat baffled, you comply and record no more revenue. In so doing, you have made a friend for life, as the two months of revenue you held back will be released by the acquiring company.

Inflating revenue right after closing on an acquisition is a pretty simple trick: once the merger is announced, instruct the target company to hold back revenue until after the merger closes. As a result, the revenue reported by the newly merged company improperly includes revenue that was earned by the target before the merger.

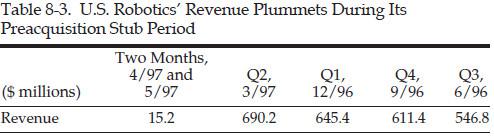

Consider the 1997 merger of 3Com with U.S. Robotics. Because the two companies had different fiscal year-ends, a two-month “stub period” was created just before the closing. Apparently, U.S. Robotics held back an enormous amount of revenue so that it would be available to 3Com after the merger closed. It appeared that 3Com included in its August 1997 quarter revenue that U.S. Robotics had deferred during the stub period. Here’s the “smoking gun”: U.S. Robotics reported a minuscule $15.2 million of revenue for the two-month stub period (approximately $7.6 million per month), a tiny fraction of the $690.2 million in revenue that the company had reported during the preceding quarter (approximately $230 million per month). Rather than recognizing the revenue during the normal course of business, U.S. Robotics apparently held back well over $600 million (see Table 8-3).

Be Alert for Lower Revenue at a Target Company Just Before It Is Acquired

Remember our friends at Computer Associates who manipulated their numbers to help senior management take home $1 billion in bonuses? We pointed out some of the many tricks the company used to accomplish this feat, including the “35-day” month and immediate revenue recognition on 10-year installment sale contracts. Well, like 3Com, Computer Associates may have also benefited from revenue that was held back before an acquisition.

Consider, for example, Computer Associates’ 1999 purchase of Platinum Technologies. During the March 1999 quarter, the last one before the deal closed, Platinum’s revenue plunged to its lowest level in seven quarters, falling by more than $144 million sequentially and by more than $23 million from the year-ago period (see Table 8-4).

Platinum attributed the sharp decline to delays in closing customer contracts as a result of its proposed acquisition by Computer Associates. Whatever the real reasons, however, Platinum’s failure to close these sales provided its new owner with an artificial revenue boost. Taking the analysis one step further, even if Platinum’s revenue drop-off was not the result of holding back revenue, investors should still be concerned that Computer Associates was buying a business with rapidly shrinking revenue.

4. Recording Current-Period Sales in a Later Period

This final section could be considered a close cousin of the previous one: holding back revenue until a later period. The previous section explored this game in the context of acquisitions. In this section, we discuss a simple trick that is less fancy: management simply decides to record the sale after the period closes, thereby holding back revenue until the later period.

Assume that late in a very strong period, management has achieved all the earnings targets needed to reach its maximum bonuses for the period. Sales continue at a brisk pace, and management has an idea that will ensure high bonus payments for the next period as well—stop recording any more sales and shift them to the next quarter. It is simple to do, it is unlikely that the auditors will even know about this trick, and your customers certainly won’t object, since they will get billed later than they expected. Nonetheless, this practice is dishonest and misleading to investors, as it portrays higher sales in the later period. More important, however, it shows that management makes business decisions that are based not on sound business practices, but on dressing up its financial reports for investors.

Looking Back

Warning Signs: Shifting Current Income to a Later Period

• Creating reserves and releasing them into income in a later period

• Stretching out windfall gains over several years

• Improperly accounting for derivatives in order to smooth income

• Holding back revenue just before an acquisition closes

• Creating acquisition-related reserves and releasing them into income in a later period

• Recording current-period sales in a later period

• Sudden and unexplained declines in deferred revenue

• Changes in revenue recognition policy

• Unexpectedly consistent earnings during a volatile time

• Signs of revenue being held back by the target just before an acquisition closes

Looking Ahead

Chapter 8 showed what management might do to hold back legitimate revenue in order to recognize it in a later and apparently more desirable period. If the goal is to shortchange the present period and benefit future-period income, accelerating expenses to earlier periods should also do the job. Chapter 9 describes a number of techniques used to accelerate expenses, making the current period seem like a disaster in order to show beautiful profits tomorrow.

9 – Earnings Manipulation Shenanigan No. 7: Shifting Future Expenses to an Earlier Period

Remember the fun children’s game called opposite day? For the kids playing the game, the object is to do things the opposite way from how they normally do them. In this chapter, let us adults have a bit of fun playing the opposite game with expenses. You recall that the whole point of Earnings Manipulation Shenanigans No. 4 and 5 was to either push expenses to a later period or simply make them disappear forever. Now, let’s get a bit creative with our accounting, in the spirit of opposite day.