Financial Shenanigans: How to Detect Accounting Gimmicks & Fraud in Financial Reports, 3rd Edition (22 page)

Authors: Howard Schilit,Jeremy Perler

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Accounting & Finance, #Nonfiction, #Reference, #Mathematics, #Management

As you might imagine, many companies were in denial about the severe drop in portfolio values and considered impairment unnecessary. At first, many financial institutions barely took any charges at all for these declines. However, as the downturn deepened, it became more difficult for companies to ignore reality and justify maintaining these assets on their Balance Sheets at inflated values.

Consider the treatment of investments by Friedman, Billings, Ramsey & Co. (FBR), an investment bank and real estate trust hybrid, in mid-2005. Despite a collapse in the value of certain investment holdings, the company kept its earnings afloat by deciding not to take any impairment charges. Management initially had plenty of reasons to justify why impairment charges were unnecessary; however, in February 2006, management did an about-face and announced $262 million in write-downs and losses on these investments.

Gauging the impairment of an asset may be one of the more difficult and subjective decisions for management, and during the credit crisis, there was little agreement among companies concerning when impairment charges became necessary. By delaying the tough decision to take the charges, many companies kept their earnings inflated, and in so doing, they sowed widespread investor distrust about the true value of their assets.

Looking Back

Warning Signs: Shifting Current Expenses to a later Period

• Improperly capitalizing normal operating expenses

• Changes in capitalization policy or accelerated capitalization of costs

• New or unusual asset accounts

• Jump in soft assets relative to sales

• Unexpected increase in capital expenditures

• Amortizing or depreciating costs too slowly

• Stretching out depreciable asset life

• Improper amortization of costs associated with loans

• Failing to record expenses for impaired assets

• Jump in inventory relative to cost of goods sold

• Failure by lenders to adequately reserve for credit losses

• Decrease in loan loss reserve relative to bad loans

• Decline in bad debt expense or obsolescence expense

• Decrease in reserves related to bad debts or inventory obsolescence

Looking Ahead

Chapter 6 described the metaphorical two-step dance that is employed to account for costs. Step 1 requires treating as assets those costs that generate long-term benefits. Step 2 requires moving those costs to expense when the benefit has been realized. Some assets (such as inventory or prepaid insurance) yield benefits quickly, while others (such as plant assets) yield them over a much longer period. Regardless, any asset that has become permanently impaired must be written off immediately.

The next chapter focuses on those costs that provide only a short-term benefit and follow a one-step process. While conceptually, all costs incurred to grow or maintain a business do provide some benefit (i.e., they remain as assets for a while), the period for these costs is quite short, and, by convention, they appear only as an expense. Shenanigan No. 5 shows techniques used by management to hide those expenses from investors.

7 – Earnings Manipulation Shenanigan No. 5: Employing Other Techniques to Hide Expenses or Losses

Failing to report all your expenses when filing your taxes with the Internal Revenue Service makes no sense, because you will only wind up with a higher tax bill. However, this trick works just fine if your goal is to impress (and deceive) your shareholders and bankers by showing higher profits. The previous chapter showed how management tries to hide expenses on the Balance Sheet, pretending that they are really assets. This chapter presents a more challenging financial shenanigan for investors to detect: when management decides not to even record certain expenses anywhere in the accounts. It’s pretty amazing that people would try this trick to begin with; what’s even more amazing is that they often get away with it!

In the previous chapter, we discussed how certain costs with long-term benefits are initially recorded as assets on the Balance Sheet, while other costs with short-term benefits are expensed immediately. We showed that monitoring trends in assets, expenses, and capitalization policies is a helpful way to catch companies that are inflating their earnings by improperly keeping costs on the Balance Sheet. In contrast, costs that provide only short-term benefits never appear on the Balance Sheet at all because they are expensed immediately. This chapter focuses on tricks related to those short-term benefits that management simply decides to hide from investors. Along the way, we will also reveal the ploy that we crown King of All Shenanigans.

Employing Other Techniques to Hide Expenses or Losses

1. Failing to Record an Expense from a Current Transaction

2. Failing to Record an Expense for a Necessary Accrual or Reversing a Past Expense

3. Failing to Record or Reducing Expenses by Using Aggressive Accounting Assumptions

4. Reducing Expenses by Releasing Bogus Reserves from Previous Charges

1. Failing to Record an Expense from a Current Transaction

The first section of this chapter discusses hiding expenses by simply failing to record all or some of an expense from various transactions.

Recording Only Part of a Transaction

A fairly simple way to hide expenses would be to pretend that you never saw an invoice from a vendor until after the quarter has ended. For example, failure to account for an electricity bill received in late March for that month’s service would underreport the expenses (and the related accounts payable), and therefore would overstate income.

Question the Failure to Record Invoices from Vendors Received Late in the Period.

Several weeks before the close of its 1999 fiscal year, Rent-Way’s accounting department stopped recording bills from vendors and the related expenses. By doing so, the company artificially reduced expenses in fiscal 1999 by $28 million, and then again in 2000 by $99 million. At the beginning of fiscal 2001, Rent-Way disclosed accounting improprieties related to underreporting $127 million of expenses during the previous two years. The stock price subsequently plummeted 72 percent, to $6.50 from $23.44.

The scheme became known when the chief accounting officer was away on vacation. The new CFO discovered that Rent-Way’s inventory system indicated that there was less merchandise in the stores than was reflected in the accounting records.

Accounting Capsule: Accruing Expenses

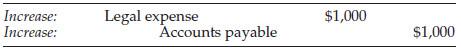

Suppose you have received something of value and you have received the invoice for it, but you have not yet paid for it. For example, suppose that on December 15, your attorney negotiates a deal for you and then sends you an invoice for her services. Here’s the correct accounting entry to record this unpaid invoice:

If you decide to put the bill in your top drawer and not record the entry until after year-end, the excluded legal expenses will inflate your profits.

Another example of failing to record end-of-period expenses involves the infamous Symbol Technologies. Symbol paid bonuses to employees in the March 2000 quarter, but failed to record the related obligation to pay $3.5 million in Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) insurance. Instead, the company inappropriately decided that it would record the expense in a later period, when the cash was paid. By failing to properly accrue the FICA expense in March, Symbol overstated its quarterly net income by 7.5 percent.

Investigate Unusual Transactions in Which Vendors Send Out Cash.

A less common ploy to artificially reduce expenses and inflate profits involves receiving sham rebates from suppliers. Naturally, this shenanigan needs the assistance of the supplier. Here’s how it works.

Tell a supplier that you will agree to purchase $9 million of office products over the next year, and that you will pay an inflated price of $10 million. In exchange for this large order, you ask the supplier to pay you a $1 million up-front “rebate” upon signing the agreement. You then improperly record the rebate as an immediate reduction of your office expenses. By using this trick, you have boosted earnings by the $1 million receipt, which should have been recorded as a reduction of the inflated price of future office supplies purchases.

Consider Sunrise Medical’s dealings with a supplier in which the company worked out a deal to receive a $1 million rebate on purchases that had already been made during the year. What was in it for the supplier? Well, Sunrise agreed to a price increase on purchases made in the next year to offset the rebate. A “side letter” was executed to seal this caper. Sunrise recorded the rebate as a decrease in expenses, without disclosing to investors or to the auditor that the supplier had tied the rebate to a price increase on future purchases.

Tip:

Always question any cash receipt from a vendor. Cash normally flows out to vendors, not in, so unusual cash inflows from vendors may signal an accounting shenanigan.

Watch for Unusually Large Vendor Credits or Rebates.

SyntaxBrillian Corp. took the concept of vendor rebates to a completely different and inappropriate level. The company received various vendor “credits” from its primary supplier (Kolin), which, as we discussed in the previous chapter, was also a significant shareholder of the company. Syntax-Brillian recorded these vendor credits as a reduction in cost of goods sold, which naturally provided a benefit to earnings. The problem was, however, that these were no ordinary credits. The size of these credits was absolutely shocking; it accounted for more than all of Syntax-Brillian’s gross profit over its brief history as a public company. Specifically, between December 2005 and June 2007, the company reported gross profit of $142.7 million, which included credits from Kolin totaling an astounding $214.7 million. Moreover, the company never received cash for these credits; they were just bookkeeping entries. As a result, Syntax-Brillian showed decent profitability, but severely negative cash flow from operations. Even novice investors could have identified this scheme. A quick quality of earnings check would have revealed a huge disparity between cash flow and net income. Moreover, diligent investors could have found in the footnotes disclosures of unusually large vendor credits and significant related-party transactions.

Failing to Properly Account for Stock Option Backdating Expense

Most shenanigans discussed in this book share a common theme: company executives use accounting gimmicks to show impressive results in hopes of driving up the stock price so that their shares and options become very valuable. The options backdating scandal that erupted in 2006 is on a whole different level of dishonesty. Executives were able to skip the whole part about using accounting gimmicks, showing impressive results, and driving up the stock price. Instead, they cut right to the chase and secretly gave themselves stock options that had already increased in value. In so doing, executives found a simple way to loot the company’s coffers without letting anyone know. They thought it was the perfect heist—and it was, until they were caught.

The King of All Shenanigans.

If you were to put options backdating on one side of a scale that weighs dishonesty, and any other shenanigan on the other side, we believe that backdating would always be heavier. Why? Because all other shenanigans are designed to enrich management in a complicated, indirect manner, while backdating does so without any serious effort at all. Look at all the “hard work” Enron executives had to do to create all those crazy joint ventures to make results appear better! Look at the acquisition activity at Tyco and the gyrations that Symbol Technologies went through in order to get positive results! And no matter how much cheating went on at these companies,

there was never a guarantee that the stock price would respond accordingly.

With options backdating, however, management barely had to lift a finger in order to cheat. And, of course, the process guaranteed a positive result. For this reason, we crown backdating as the King of all Shenanigans

.