Financial Shenanigans: How to Detect Accounting Gimmicks & Fraud in Financial Reports, 3rd Edition (37 page)

Authors: Howard Schilit,Jeremy Perler

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Accounting & Finance, #Nonfiction, #Reference, #Mathematics, #Management

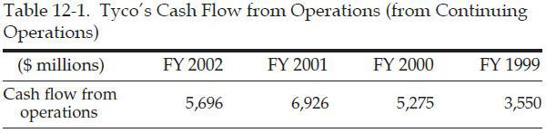

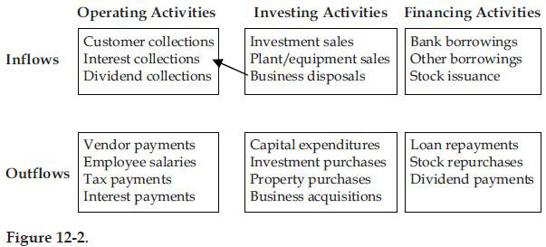

Treat CFFO Differently for Acquisitive Companies. Since acquisitions create an unsustainable boost to CFFO, investors should not blindly rely on CFFO as a barometer of performance. Use free cash flow after acquisitions to assess cash generation at acquisitive companies. Table 12-2 shows that Tyco recorded negative free cash flow after acquisitions each year, despite reporting positive CFFO; this was a warning

that operating cash flow was not what it appeared to be.

Tip:

“Free cash flow after acquisitions” is a useful measure of cash flow when analyzing serial acquirers. This metric can easily be calculated from the Statement of Cash Flows: CFFO minus capital expenditures

minus

cash paid for acquisitions.

Review the Balance Sheets of Acquired Companies.

If these documents are available, then by all means review them. Doing so should help you gauge the potential inherent working capital benefits.

It may be difficult to be precise in this analysis; however, you often will be able to make an assessment that is within the “ballpark” of the potential benefit. Companies often disclose the Balance Sheets of larger acquisitions and sometimes an aggregate Balance Sheet for smaller ones in their footnotes. If the acquired company had publicly traded stock or bonds, you can probably obtain a Balance Sheet from public records.

2. Acquiring Contracts or Customers Rather Than Developing Them Internally

In the previous section, we discussed how acquisitions, by their very nature, provide a boost to CFFO. This benefit results not from illegitimate accounting maneuvers, but rather from quirky accounting rules. We witnessed Tyco abusing the rules by quietly snapping up hundreds of small companies and finding ways to squeeze even more CFFO out of these acquisitions.

In this section, we take a step into more nefarious terrain and explore how companies use the acquisition accounting loophole for nonacquisition situations to shift normal operating cash flows to the Investing section.

Witness Tyco (again) and its electronic security monitoring business. Home security monitoring was a fast-growing business in the 1990s, and Tyco’s ADT division proved to be among the most popular brand names. Tyco generated new security systems contracts in two ways: through its own direct sales force and through an external network of dealerships. The dealers allowed Tyco to outsource a portion of its sales force. They were not on Tyco’s payroll, but they sold security contracts, and Tyco paid them about $800 for every new customer.

Oddly, Tyco executives did not view these $800 payments to dealers to be normal customer solicitation costs, as the economics would suggest. Instead, they deemed these payments to be a purchase price for the “acquisition” of contracts. Thus, after the dealer presented Tyco with a number of contracts and received payment, Tyco curiously accounted for these “contract acquisitions” in the same way that it accounted for normal business acquisitions: as Investing outflows.

Given how deeply the acquisition mentality was engrained in Tyco’s culture and DNA, you can almost picture confusion among its executives. Almost. These customer solicitation costs resemble normal operating expenditures much more closely than they resemble business acquisitions. As a result, it makes more sense for them to be recorded on the Statement of Cash Flows in the same way that Tyco’s internal sales force commissions are recorded: as Operating outflows. By classifying these operating outflows in the “acquisitions” line in the Investing section, Tyco found a convenient way to overstate CFFO.

And the company didn’t stop there!

From Aggressive Accounting to Fraud

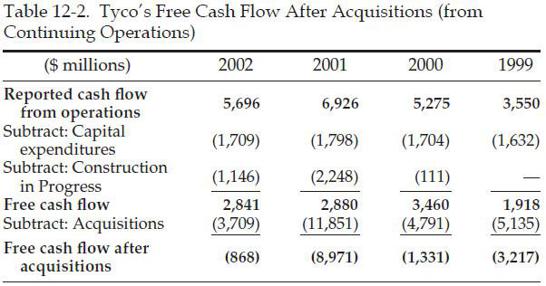

By turning the Investing section into a hidden dumping ground for customer solicitation costs, Tyco aggressively and creatively twisted the accounting rules. But the company still wanted more. So it concocted a new scheme to inflate CFFO (and earnings) even further, and in so doing, crossed the line from aggressive accounting to fraud. The SEC charged that from 1998 to 2002, Tyco used a “Dealer Connection Fee Sham Transaction” to fraudulently generate $719 million in CFFO. Here’s how it worked.

For every contract Tyco purchased from a dealer, the dealer would be required to pay an up-front $200 “dealer connection fee.” Of course, the dealers would not be happy about this new fee, so Tyco raised the price at which it would purchase new contracts by the same $200—from $800 to $1,000. The net result caused no change in the economics of the transaction—Tyco was still paying a net of $800 to purchase these contracts from dealers.

However, Tyco did not see it that way. After all, the company would not have created the ruse if it didn’t think that it would prove to be beneficial in the end. Tyco now recorded a $1,000 Investing outflow for the purchase of these contracts, and an offsetting $200 as an Operating inflow. Essentially, Tyco created a bogus $200 CFFO inflow by depressing its Investing cash flow. (See Table 12-3.) Over the course of five years and hundreds of thousands of contracts, this was quite a contribution to CFFO!

3. Boosting CFFO by Creatively Structuring the Sale of a Business

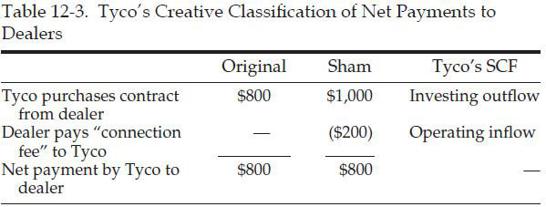

In the previous two sections, we showed how companies use acquisitions to shift cash

outflows

from the Operating section to the Investing section of the SCF. In this next section, we discuss the flip side of that coin: how companies use disposals to shift cash inflows from the Investing section to the Operating section, as shown in Figure 12-2.

Recording CFFO for Proceeds from the Sale of a Business

In 2005, Softbank structured an interesting two-way arrangement with a fellow Japanese telecom company, Gemini BB. Softbank sold its modem rental business to Gemini, and simultaneously, the companies entered into a “service agreement” in which Gemini would pay Softbank royalties based on the modem rental business’s future revenue. At the time of the sale, Softbank received ¥85 million in cash from Gemini, but it did not consider the entire amount to be related to the sale price of the business, according to a report by RiskMetrics Group. Instead, Softbank decided to split the cash

received into two categories: ¥45 million was allocated to the sale of the business, and ¥40 million was deemed to be an “advance” on the future royalty revenue stream. (You may recall the earnings boost that this transaction provided, as discussed in EM Shenanigan No. 3.)

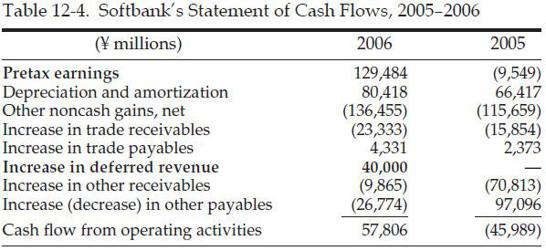

The economic reality of this situation seems to be that Softbank sold its modem rental business for ¥85 million. However, the way it structured the transaction seemingly allowed Softbank to exercise discretion in its presentation of cash flow. Rather than recording an ¥85 million Investing inflow from the sale of the business, Softbank recorded (1) a ¥45 million Investing inflow from the sale of the business and (2) a ¥40 million Operating inflow from the “advance” on future revenue. This ¥40 million boost to CFFO represented 69 percent of Softbank’s ¥57.8 million in CFFO for the full year.

Watch for New Categories on the Statement of Cash Flows.

Investors could easily have spotted Softbank’s CFFO boost just by looking at the Statement of Cash Flows. Take a look at Table 12-4, and note that a new line item surfaced in 2006—a ¥40 million “increase in deferred revenue.” This Statement of Cash Flows disclosure, together with the magnitude of its impact on CFFO, would be reason enough for astute investors to dig deeper.

Sell the Business, but Keep Some of the Good Stuff

Tenet Healthcare is a company that owns and operates hospitals and medical centers. In recent years, Tenet has been selling some of its hospitals in order to improve its liquidity and profitability. It often plays a neat little CFFO-enhancing trick when structuring the sale of these hospitals—it sells

everything but the receivables.

Let’s discuss how this works. Think of each hospital as being its own little business, with revenue, expenses, cash, receivables, payables, and so on, just like any other company. Before putting a hospital up for sale, Tenet strips the receivables out of the business. In other words, if a hospital has, say, $10 million in receivables, Tenet keeps the rights to those receivables and puts the rest of the business up for sale. This, of course, lowers the eventual sale price of the hospital by about $10 million, but Tenet couldn’t care less, as it recoups that amount when it collects the receivables.

What are the implications with regard to cash flow? Well, normally all proceeds from selling a hospital would be recorded as an Investing inflow ( just like the sale of any business or fixed assets). However, by stripping out the receivables prior to the sale, Tenet lowers the sale price (and the Investing inflow) by $10 million. However, the company will soon collect the $10 million from its former customers, and here’s the nice part: all the proceeds will be reported as an Operating inflow, since it is related to the collection of receivables. This trick allowed Tenet to shift the $10 million inflow from the Investing to the Operating section.