Fearless on Everest: The Quest for Sandy Irvine (33 page)

Read Fearless on Everest: The Quest for Sandy Irvine Online

Authors: Julie Summers

Tags: #Mountains, #Mount (China and Nepal), #Description and Travel, #Nature, #Adventurers & Explorers, #Andrew, #Mountaineering, #Mountaineers, #Great Britain, #Ecosystems & Habitats, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Irvine, #Everest

After visiting the temple he spent a good hour watching some novices in the monastery turning a prayer wheel. His absence from camp had been noticed and after he had been ‘missing’ for over two hours Somervell and Noel went off to see if they could find him. They spotted him standing some distance away, with his hands in his pockets, shoulders hunched, studying the monks at the prayer wheel with great concentration. ‘What is Irvine doing?’ asked Noel. ‘I expect he’s trying to work out how to mechanize it for them,’ was Somervell’s response.

From Shekar Dzong they had a five-day trek to the site of their Base Camp at the foot of Everest. This final leg of the march was a bit of a struggle for Sandy. The wind was vicious and carried tiny stones and sand from the plain which cut his badly sunburned face and caused him considerable pain. In addition, he had been feeling unwell since leaving Shekar Dzong. He complained of feeling ‘seedy’ which was the description he used when he was not 100 per cent fit. On this occasion he attributed it predominantly to the fact that he had been up until midnight or 2 a.m. most nights working on the oxygen apparatus and then rising each morning at 6.30 a.m. and trekking twelve to fifteen miles each day, mostly on foot. When he was not feeling well his temper was short and his diary entries betrayed his frustrations: ‘my blasted pony trod on my walking stick and broke it’ he wrote two days after leaving Shekar Dzong. Despite this, he still kept up his usual cheerful outward appearance and no one appeared to be aware of anything untoward. When he arrived in camp in Tashi Dzong he put himself straight to bed in his tent, only to be woken an hour later by Mallory with a box of crampons. ‘I spent until dinner time fitting crampons to Mallory and my boots and trying to fix them without having a strap across the toes which is likely to stop the circulation. Inside feels all wrong but still have a good appetite.’ Like his father, Sandy had learned how to dose himself up with a variety of medicaments to cure his problems. This time he took four castor oil tablets but noted they had the opposite of the desired effect.

The next day he was feeling no better as they trekked from Chodzong to Rongbuk. The monastery at Rongbuk was the last outpost of civilization before they reached Everest Base Camp. The monastery, or the ruins of it today, to be precise, stands half way down the Rongbuk valley, about eleven miles from the site of the 1924 base camp. The valley is some eighteen miles long and rising only 5000 feet is overwhelmed at its head by the mass of Everest, dominating the view with its huge bulk and dramatic pyramid, from which, so often, there flows a stream of snow. The name Rongbuk means Monastery of the Snows. Long before the first European expeditions came to the Himalaya, the great peaks were places of pilgrimage. It would never have occurred to the Tibetans to climb the mountain, for they represented the domain of the gods. But the pilgrims came to worship and meditate, and the monastery at Rongbuk was the place the pilgrims visiting Chomolungma would stay. The monks were supplied with food by the pilgrims who came to worship, bringing with them presents of flour, yak butter, warm materials and other gifts.

When the expedition arrived at Rongbuk on 28 April the Holy Lama, ngag-dwang-batem-hdsin-norbu, was unable to see them as he was ill. This was something of a disappointment as they had hoped to be able to receive a blessing from the lama before they began their approach to the mountain. Such a blessing was held in particularly high regard by the porters who understood that the lama would be able to pray for their safety from the demons of the mountain. He became a friend to all the Everest expeditions of the 1920s and 1930s and this was in no small part due to his meeting with General Bruce in 1922, with whom he established a rapport. Bruce had explained to the lama that ‘his climbers were from a British mountain-worshipping sect on a pilgrimage to the highest mountain in the world’. He had sought to convey to him that the motives the expedition had for climbing the mountain were not in any way for material gain but were entirely spiritual. As the lama was indisposed Norton had to content himself with making gifts and exchanging greetings with the other monks and promising to return if the Holy Lama, when better, would grant them an audience and bless the expedition. The lama let it be known that he would give them an audience on 15 May.

Norton was very pleased to see at Rongbuk the Shika, or head man, from Kharta with whom he and others on the 1922 expedition had formed good relations. The Shika was paying his respects to the Head Lama when they met this year and Norton was able to tell him that they had already sent him greetings and presents from Shekar Dzong three days earlier. The Shika, in return, promised to send them a consignment of fresh green vegetables and luxuries. This was very welcome news to Norton and the others for such things were otherwise unobtainable in this inhospitable district.

As Norton was paying his respects at the monastery and arranging for the audience with the Holy Lama, Sandy was once again huddled in his tent mending things. This time it was Beetham’s camera, Mallory’s saddle and his own sleeping bag. His health and mood did not improve the next day when they finally arrived at the place below the mountain where they were to put up their Base Camp – their ‘refuge’ for the next two months. ‘Bloody morning, light driving snow, very cold and felt rather rotten …Walked all the way from Rongbuk monastery to the base camp 1¾ hours over frozen river and very rough terrain. The Base Camp looked a very uninviting place.’

Irvine is the star of the new members. He is a very fine fellow, has been doing excellently up to date & should prove a splendid companion on the mountain. I should think the Birkenhead News ought to have something to say if he and I reach the top together.

G. L. Mallory to his mother, 26 May 1924

Situated eleven miles from the Rongbuk monastery, at the foot of the Rongbuk glacier, Everest Base Camp was a bleak place. No sign of vegetation, dominated by the bulk of Everest and frequently in shadow, its rocky, rough terrain was uninviting at best. It was, however, to be home to the expedition party for the next six weeks and it became a veritable little village of tents with comings and goings of porters, tradesmen, interpreters, messengers and the all-important postal service.

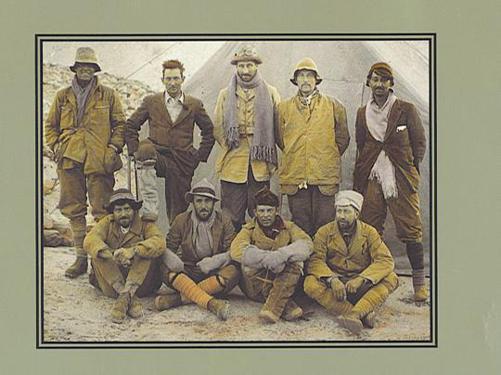

The expedition at Base Camp, photographed by Captain John Noel

The expedition at Base Camp, photographed by Captain John Noel

Back row l-r Sandy Irvine, George Mallory, Edward Norton, Noel Odell, John MacDonald

Seated l-r John Hazard, Geoffrey Bruce, Howard Somervell, Benthley Beetham

Norton described the approach in a

Times

dispatch on the day they arrived. ‘Today, April 29, finds us again in the 1922 Base Camp and a cold welcome we have received. We walked over five rough miles of tumbled moraine and a frozen watercourse to the camp just under the snout of the Rongbuk glacier, in the teeth of a bitter wind. Here, indeed, it is winter.’ Despite the inhospitable conditions they encountered and the ever-present wind that whistled down the Rongbuk Valley off the glacier in the afternoons leaving the temperature at Base Camp well below freezing, there was a feeling of great optimism in camp. Everyone was busy with his allotted task of sorting, checking, repairing the stores. Mallory and Beetham were in charge of the high altitude Alpine equipment to be sent to the upper camps; Shebbeare and Hazard were occupied with labeling the boxes of stores which had been dumped unceremoniously off the transport animals the day before; Somervell was busy with the medical and scientific stores and Sandy and Odell were locked in their usual, daily battle with the oxygen apparatus. And a battle it had indeed become. Working at Base Camp was hard and the climbers all felt the lack of oxygen at 17,800 feet. Even taking off their boots and climbing into their sleeping bags left them breathless. Sandy wrote in his diary: ‘felt rather exhausted with the altitude. A simply perfect day, everyone working like mad sorting stores. I spent an hour or so on Beetham’s camera and the whole of the rest of the damn day on oxygen apparatus.’ The next day he was hard at it again: ‘completed the repair of Beetham’s camera and spent the whole of the day struggling with the infernal apparatus.’ By 6.30 p.m. that day he had his first perfect set which he put outside his tent to see if the solder would crystallize in the freezing air. The struggle was made all the more difficult by the fact that he was having to work inside his tent with the doors closed. ‘Another full day at the ox app with an incredible number of reverses. Sweating in the HP tubes is a difficult job at the best of times, but cramped in a tent (too windy outside) it was a perfect devil – on every possible occasion the solder would flow and break the HP tube which meant reheating at the risk of the pressure gauge and blowing the tube clear. By 6pm tonight I had 6 done and all sound except one which leaked in the HP tube itself.’ I sense from these three diary entries that he had lapsed into a state of rising panic about the oxygen apparatus. The conditions under which he was working were far from ideal and his tool kit was at best basic. Furthermore he knew that the oxygen apparatus would be required soon and should be ready to be carried up to the higher camps quickly. He was also aware that work was taking him out of the picture as far as the other climbers were concerned and was clearly worried that if he did not complete the work he would get behind in the climbing schedule.

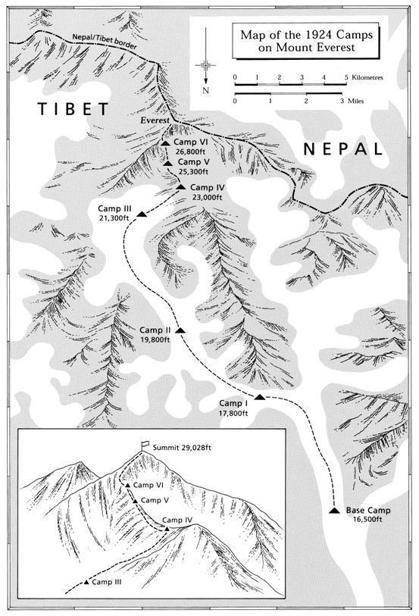

Each camp had its own diary in which the climbers all made entries about a variety of matters, from the state of stores to accounts of their climbing experiences. In the Base Camp diary there was the plan of campaign neatly written out so that each climber knew exactly where he was expected to be at any one time and, more importantly, where on the mountain his colleagues were to be. From the outset the two climbing teams, Norton and Somervell, and Mallory and Sandy, were scheduled to make their acclimatization trips prior to the summit assault together. Sandy and Mallory were to be the first team to set off and occupy the higher camps where they would be overtaken on 15 May by Norton and Somervell who would be setting two camps (V and VII) on 15 and 16 May. The other two would be resting on the 15 at Camp IV and pushing to an intermediate camp, No. VI, on the 16, so that both would be making the summit attempt on the 17, but from different camps. This would give them three camps to retreat to on the way down if necessary and provide oxygen support if the non-oxygen party, Norton and Somervell, got into difficulties.

May 2 was Sandy’s last day in Base Camp and he spent it working flat out on the apparatus. In his lengthy diary entry for that day he goes into great detail about the repairs, alterations, modifications he made but I sense a great feeling of relief that, in the end, he had been able to make it work to his satisfaction. As an encore that afternoon he repaired a roarer cooker which had been brought to his workshop tent two days earlier and shortened Mallory’s crampons by half an inch: ‘in so doing I spiked one hand and burnt the other in 2 places so was glad Nima didn’t understand my French accent! I reduced the tool box as much as I dared to send up to Camp III’. He was ready on time, scheduled to leave the following day with Mallory, Odell and Hazard to climb past Camps I and II to III. ‘I hope to put up a good show when the altitude gets a bit trying. I should acclimatize well at III the time we will spend there.’

Geoffrey Bruce was the man charged by Norton with the responsibility of stocking the first two camps above Base Camp, Camp I at the foot of the East Rongbuk glacier, at 17,800 feet, three miles from Base and Camp II, three miles further up the glacier at 19,800 feet. These camps were to be set up by the Gurkha NCOs in order to conserve, as far as possible, the energy of the climbers by keeping them at Base Camp and not requiring them to haul loads at this stage. The actual portering to Camps I and II was done by 150 Tibetans whom Bruce had recruited in Shekar Dzong with permission from the Dzong Pen. The condition of their employment was that they would be given some rations and paid four

tankas

a day (about 1s or 5 pence, nowadays worth about £1.50) and that they would not be employed on snow or ice. The Dzong Pen had asked that they be quickly released after their work was done as they were needed to sow crops and attend to their fields on their return. The Tibetans undertook to look after themselves in all other respects, which meant that they were quite happy to sleep out in the open at 18,000 feet with neither tents nor blankets. ‘Had they been of a less hardy race, their maintenance in such country would have been well nigh impossible.’ Geoffrey Bruce admitted later.