Fateful Lightning: A New History of the Civil War & Reconstruction (15 page)

Read Fateful Lightning: A New History of the Civil War & Reconstruction Online

Authors: Allen C. Guelzo

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #U.S.A., #v.5, #19th Century, #Political Science, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Military History, #American History, #History

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

was Stowe’s first novel, but it drew on a wealth of observation she had acquired when living in Cincinnati in the 1840s while her husband was a professor at Lane Theological Seminary, and a wealth of reading she had done in slave narratives (including that of Josiah Henson, who turns up in

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

as one of the models for Uncle Tom). In 1851 her sister-in-law urged her to “use a pen if you can” to denounce the Fugitive Slave Law and “make this whole nation feel what an accursed thing slavery is.” “I will if I live,” Stowe announced, and one Sunday shortly thereafter in church, the plot and characters of the novel broke upon her “almost as a tangible vision.” The novel poured out of her pen in a matter of

weeks, sentimental and mushy and short on story line, but faultless in its character construction and perfect in its appeal to a sentimental and mushy age.

37

The plot can be stated briefly: Tom, the faithful slave of the Shelby family, is sold away from his Kentucky home to pay the debts of his guilt-ridden master. He is purchased by a Louisiana planter, the disillusioned Augustine St. Clare, who believes that slavery is wrong but who cannot imagine a way of life without slaves. Tom wins the hearts of the St. Clare household, especially St. Clare’s frail daughter, Little Eva. In what may be the most saccharine-laden chapter in American literature, Little Eva dies and the remorseful St. Clare resolves to free his slaves. Before that can happen, St. Clare is stabbed in a brawl, and when he dies, Tom is not freed. Instead, he is sold to Simon Legree, whose unalloyed villainy drives him to murder the hymn-singing Tom just before George Shelby, the son of Tom’s old master, arrives to purchase to his freedom. As if this were not enough, Stowe throws in some hair-raising adventure to off set the tackiness of the plot: the escape of the runaway Eliza Harris, who eludes the slave catchers by dashing across the wintry Ohio River, her infant son in her arms, leaping precariously from ice floe to ice floe, and a shootout between Eliza’s husband, George Harris, and the slave-catching posse.

The real genius of the book, however, lies in the care with which Stowe made her chief attack on slavery itself rather than merely taking quick shots at slaveholders. Slavery, for Stowe, was a nameless evil that held well-intentioned Southerners such as the Shelbys and St. Clares as much in its grip as any slave. Stowe made her readers hate slavery, and she made them hate the Fugitive Slave Law, too, for her immediate objective was to awaken Northerners to the hideous realities the new law was bringing to their own doorsteps. “His idea of a fugitive,” wrote Stowe of one stunned Northern character, John Bird, who finds a half-frozen Eliza Harris in his kitchen,

was only an idea of the letters that spell the word… The magic of the real presence of distress,—the imploring human eye, the frail trembling hand, the despairing appeal of helpless agony,—these he had never tried. He had never thought that a fugitive might be a hapless mother, a defenseless child,—like that one which was now wearing his lost boy’s little well-known cap.

38

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

began as a serial in the anti-slavery newspaper

National Era

on June 2, 1851, and ran until April 1, 1852. When it was issued in book form, 3,000 of the first 5,000 copies flew from booksellers’ stalls on the first day of publication; within

two weeks it had exhausted two more editions, and within a year it had sold 300,000 copies.

39

The controversial captures of runaways and the sensational impact of

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

made the Fugitive Slave Law into the Achilles’ heel of the Compromise of 1850. Northerners who were otherwise content to leave slavery where it was so long as it stayed where it was now found themselves dragooned into cooperation with the South in supporting and maintaining slavery. And as they turned against the Fugitive Slave Law, they began to question the entire Compromise of 1850.

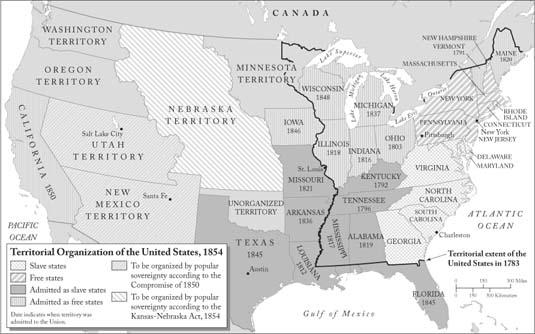

They had good reason, too, especially as the much-vaunted cure-all, popular sovereignty, increasingly came to seem more like a placebo. Initially, the Compromise had allowed the organization of the New Mexico and Utah territories by the popular vote of the people of the territory, which gave some superficial hope that popular sovereignty might be the key of promise; that, in turn, tempted politicians such as Stephen Douglas to talk a little too confidently from both sides of their mouths. Although Douglas personally had little desire to see slavery taken into the territories, popular sovereignty allowed him to tell Southerners that they had no one but themselves or the climate of the territories to blame if slavery failed to take root there; while to Northern audiences Douglas could claim that since New Mexico and Utah were poor candidates for cotton growing and would be unlikely to apply for statehood for another hundred years, popular sovereignty was the safest guarantee that slavery would not be transported to the territories. To both North and South, Douglas could promise that popular sovereignty would ensure a normal and democratic result to the process of territorial organization.

It was this apparent ease with which popular sovereignty promised to charm away all difficulties that led Douglas to carry it one step too far. Eager to open up the trans-Mississippi lands to further settlement (and, incidentally, position Douglas’s Illinois as a springboard for a new transcontinental railroad), Douglas and the Senate Committee on Territories (which he chaired) presented a new bill to the Senate on January 4, 1854, which would organize another new territory—Nebraska—on the basis of popular sovereignty, with “all questions pertaining to slavery in the Territories, and in the new states to be formed therefrom… to be left to the people residing therein, through their appropriate representatives.” (After some brief reflection, Douglas agreed to split the proposed Nebraska Territory into two separate territories, with the southernmost section to be known as the Kansas Territory.)

40

This proposal dismayed Northern congressional leaders, not only because they remained uneasy about popular sovereignty but also because the proposed Kansas and Nebraska Territories both lay within the old Louisiana Purchase lands and above

the old 36°30′ line, in the area the Missouri Compromise had forever reserved for free settlement. The compromisers of 1850 had agreed to use popular sovereignty as the instrument for peacefully organizing the territories acquired in the Mexican Cession; no one had said anything in 1850 about applying the popular sovereignty rule to the Louisiana Purchase territories. The state of Iowa, for example, had been organized as a free territory and admitted as a free state in 1846 precisely because it lay within the Missouri Compromise lands and above 36°30′, and there were many in Congress who assumed that Kansas and Nebraska ought to be organized under the same, older rule.

By 1854 popular sovereignty had whetted Southern appetites for more. Douglas knew well that the South would balk at the organization of two more free territories in the area the Missouri Compromise reserved for free settlement. They would balk even more as soon as they realized that if the proposed Kansas and Nebraska Territories were organized on the Missouri Compromise basis as free soil, the slave state of Missouri would be surrounded on three sides by free territory. It would become nearly impossible for Missouri to keep its slave population from easily decamping for freedom, and that would tempt Missouri slaveholders to cut their losses, sell off their slaves, and allow Missouri to become a free state that would block further slave state expansion westward. “If we can’t all go there on the string, with all our property of every kind, I say let the Indians have it forever,” wrote one Missouri slaveholder. “They are better neighbors than the abolitionists, by a damn sight.”

41

Douglas also knew equally well that Northerners would howl at the prospect of scuttling the Missouri Compromise and opening Kansas and Nebraska to so much as the bare possibility, through popular sovereignty, of slavery. Salmon P. Chase, the anti-slavery Democratic giant of Ohio, tore into Douglas’s Kansas-Nebraska bill with “The Appeal of the Independent Democrats” in the

National Era

on January 24, 1854, savagely attacking Douglas and accusing him of subverting the Missouri Compromise in the interest of opening Kansas and Nebraska to slavery. “The thing is a terrible outrage, and the more I look at it the more enraged I become,” Maine senator William Pitt Fessenden confessed. “It needs but little to make me an out & out abolitionist.” Mass protest meetings were held in Boston’s Faneuil Hall, in New York City, and in Detroit, as well as in Lexington, Ohio, and Marlborough, Massachusetts—at least 115 of them across the North—and resolutions attacking the Kansas-Nebraska bill were issued by five Northern state legislatures.

42

Douglas was a gambler, and he was gambling that the song of popular sovereignty would lull enough anti-slavery sensibilities to get the Kansas-Nebraska bill through Congress. He was right. He had the ear of the Pierce administration and the whip handle of the Democratic Party in Congress, and on March 3, 1854, he successfully bullied the Kansas-Nebraska bill through the Senate. It was a closer call in the House, where Kansas-Nebraska slipped through on a thirteen-vote margin on May 22, but it gave Douglas what he wanted. James M. Mason, who had read the dying Calhoun’s demand for an open door into the territories for slavery in 1850, happily prophesied that the Kansas-Nebraska bill “bore the character of peace and tended to the establishment of peace.” His fellow senator from Ohio, Benjamin Franklin Wade, could not have disagreed more. Instead, declared the acid-tongued Wade, the Kansas-Nebraska bill was “a declaration of war on the institutions of the North, a deliberate sectional movement by the South for political power, without regard for justice or consequences.” As the Senate cranked ponderously toward its vote, Wade pointed to a portent of gloom: “Tomorrow, I believe, there is to be an eclipse of the sun.” How appropriate that “the sun in the heavens and the glory of this republic should both go into obscurity and darkness together.”

43

True to the omen of the eclipse, it was at this point that the entire doctrine of popular sovereignty began to come unraveled.

When Stephen Douglas spoke of popular sovereignty, it was clear that he imagined a peaceful territory filling up gradually with contented white settlers (and evicting, if necessary, any contented Indian inhabitants); eventually there would be enough white settlers on hand to justify an application for statehood and the writing of a state constitution. “The true intent and meaning of this act [is] not to legislate slavery into any territory or state, nor to exclude it therefrom, but to leave the people thereof perfectly free to form and regulate their domestic institutions in their own way.” Beyond that, no one—especially not in Washington—had any business second-guessing the popular will. If a territory, declared Douglas, “wants a slave-State constitution she has a right to it… I do not care whether it is voted down or voted up.”

44

It seems never to have occurred to Douglas before Kansas-Nebraska that popular sovereignty might also mean that if a majority of anti-slavery settlers could camp in Kansas or Nebraska before any equal numbers of slaveholding settlers (or vice versa), that simple majority would determine the slave or free status of the territory and its

future status as a state. Douglas also ignored the possibility that there might be other ways, not necessarily gradual and painless, of achieving majorities.

This, of course, is precisely what happened in the new Kansas Territory. Antislavery New Englanders organized a New England Emigrant Aid Society in the summer of 1854 to send trains of armed anti-slavery Northerners to Kansas; in Missouri, bands of armed pro-slavery whites crossed over the border into Kansas to claim it for slavery. In the process, both sides learned yet another way of creating majorities, namely, by killing off one’s opponents, and so a fiery sparkle of violent clashes and raids between pro-slavery and anti-slavery emigrants danced along the creeks and rivers of the new territory. And by the time a territorial governor, Andrew Reeder, had been dispatched by Congress to supervise a preliminary territorial election, the Missourians had developed yet another variation on popular sovereignty—sending “border ruffians” over into Kansas on voting days to cast illegal ballots.

45

The situation only grew worse in the spring of 1855, when Governor Reeder called for elections to create a territorial legislature for Kansas. The “border ruffians” crossed over in droves to vote for pro-slavery candidates for the legislature, and when the balloting was over and some 5,400 votes for pro-slavery candidates had materialized from the 3,000 eligible white male voters of the Kansas Territory, it was clear that the election had been stolen. The beleaguered Governor Reeder was too intimidated by the “border ruffian” gangs to invalidate the election, and the new legislature, ignoring Reeder’s vetoes, enacted a territorial slave code so severe that even verbal disagreement with slavery was classified as a felony. President Pierce, still staked to popular sovereignty, refused to take any action.

46