Fateful Lightning: A New History of the Civil War & Reconstruction (11 page)

Read Fateful Lightning: A New History of the Civil War & Reconstruction Online

Authors: Allen C. Guelzo

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #U.S.A., #v.5, #19th Century, #Political Science, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Military History, #American History, #History

Content, that is, until the time came for Americans to deal with the West.

At the end of the Revolution, the outward fringe of the thirteen newly independent United States stopped pretty much at the foothills of the Appalachians. But the British surrendered to the American republic complete title to all their remaining colonial lands below Canada, stretching west beyond the Appalachians to the Mississippi River. Then, in 1803, President Jefferson bought up 830,000 square miles of old Spanish land beyond the Mississippi River for the United States for $15 million in spot cash from Napoleon Bonaparte, who had finally despaired of his project to re-create a French colonial empire in America. Both the midwestern land won from the British and the western lands bought by Jefferson originally had next to nothing in the way of American settlers in them, but there was no reason any of them could not soon fill up with settlers, organize themselves as federal territories, and then petition Congress for admission to the Union as states on an equal footing with the original states.

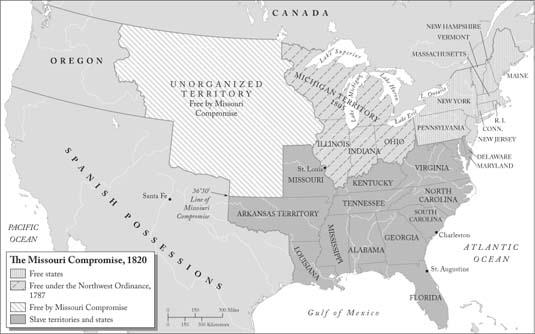

Because the Northwest Ordinance had already barred slavery from the upper midwestern land, the territories of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Michigan all entered the Union as free states; slaveholders, skirting southward below the Ohio River, were content to organize Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, Kentucky, and Louisiana as states where slavery would remain legal. The trouble began when people started to look westward, beyond the Mississippi, where no Northwest Ordinance mandated the slave or free status of the land. Southerners anxious to keep open the way to new cotton land reasoned fearfully that if nonslaveholding Northerners squatted in the Louisiana Purchase lands and settled them as free states, the South could easily find itself barricaded in behind the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers. Surrounded by free states on the Mississippi and Ohio lines, and by Louisiana’s border with Spanish-held Mexico, cotton and slavery would suffocate, no matter what the Constitution said.

And so came the first of the great angry Southern demands for assurances about the future of slavery, in the form of the Missouri controversy of 1819, and with that controversy, the first in a series of threats that the slave states would leave the Union if sufficient assurances were not forthcoming. Then, and again in 1850, slaveholders would turn the Garrisonian gospel on its head and ask the rest of the United States to choose between slavery and the Union. Both times, desperate politicians would find a way to avert the choice, until finally, in 1861, the choice had to be made.

And the war came.

THE GAME OF BALANCES

T

he fatal sequence of public events in the United States that stretched from 1820 until 1861 and the outbreak of the American Civil War can be visualized as a game of balances, with the Union as the balance point along the beam, and the two trays representing the interests of North and South, slave and free. During those years, the federal Union became increasingly threatened and unstable as states or sections or interests laid the weight of their demands on one or the other of the trays and waited to see if the other states or sections or interests would produce reassurances and compromises weighty enough to right the balances.

Of all the issues that divided Americans and provoked them to threaten that equilibrium—tariffs, trade, banks, reform—nothing proved so heavy or so liable to plunge the balance off the table entirely as slavery. Slavery pitted cultures, economic interests, and moral antagonisms against each other; worse, it pitted states against other states; worst of all, it pitted whole associations of states (in this case, the South), which could plausibly regard themselves as a nation, against other whole associations of states (namely, the free North of the old colonies and the free West of the Northwest Ordinance). It was bad enough that in 1832 one single state had been willing to defy and disrupt the Union over the tariff question. It was almost unimaginable what might happen if several states, sharing common borders in a common section of the country, with a common culture and common economy, came to believe that their very way of life was at stake, and decided that self-preservation required disunion. Had slavery been legal only in far-removed places such as Minnesota and Florida, or Maine and Alabama, it is hard to see anyone there arguing that they could stand independently on their own among the nations of the world. There would be no

such difficulty, however, if the fifteen slave states were grouped together in a single landmass, comprising 750,000 contiguous miles, and thus able to cooperate, communicate, and support one another. They would look like a nation, rather than just islands of complaint.

So long as some Americans still believed that the Union was

only

a federal union—only a league or federation of quasi-independent states that could be terminated at will—and so long as Southerners continued to believe that northern anti-slavery attacks on slavery constituted a real and present danger to Southern life and property, then disunion could not be ruled out as an ugly resort. And if the Northern states, and the federal government in Washington, failed to place on their balance pan a weight of assurances equal to Southern demands for reassurance about slavery, then the South would drop onto its pan the immense and destructive weight of disunion and the balance would be wrecked, perhaps forever.

That made the threat of secession useful.

The key word in understanding the South’s behavior throughout the four critical decades before the Civil War is

threat

. The Union had increasingly taken on the lineaments of a nation ever since the ratification of the Constitution, no matter what the secession-mongers liked to say, and the American Constitution had become increasingly intertwined with the idea of an American nation. It would always be easier to challenge both the Union and the Constitution in fustian rhetoric, but in practice, compromise within the Constitution would always get the greatest applause. Of course, in any compromise situation, threats are the weightiest chips to bargain with. So from the 1820s onward Southerners would begin talking a great deal about seceding from the Union, but frequently it was little more than intimidating talk, meant to squeeze out concessions during the compromise process rather than to announce action. There were few Southerners in 1820 who seriously wanted to leave the Union, and most of them lived in South Carolina. But Southerners were willing to

talk

secession because of the leverage such talk easily acquired within a federal union. If it was believed that disunion was a possible political outcome of the balancing game, then using secession as a threat could be highly useful in cajoling favorable responses out of the rest of the Union. “It has come to this,” complained one Northern senator, “that whenever a question comes up between the free States and the slave States of this Union, we are to be threatened with disunion, unless we yield.”

1

It mattered little enough whether secession was likely or even desirable, or whether in fact the balance itself was far more indestructible than any of the players realized. So long as the threat of secession and disunion continued to pry assurances out of the rest of the country that slavery would never be imperiled, then the South would stay in the Union.

YOU HAVE KINDLED A FIRE

”

The first round of threats and assurances played out in February 1819, when Missouri applied for admission to the Union with a state constitution that legally recognized slavery. Missouri’s application was a moment for celebration, since it was the first territory that lay entirely west of the Mississippi, in the Louisiana Purchase lands, to apply to Congress for statehood. What was less obvious was that Missouri’s petition also represented a challenge to the free states, since the Union in 1819 was perfectly balanced between eleven free states and eleven slave states. Allow Missouri to enter the Union as a slave state, and it would add two “slave” senators to the Senate and an indeterminate number of representatives to the House (artificially swollen, as Northerners saw it, by the three-fifths rule). That, in turn, might give the South enough of an edge in Congress to disrupt the Northern campaign to protect American manufacturing and weaken the demands of Henry Clay and the National Republicans for an “American System” of federally tax-supported roads, turnpikes, canals and other “internal improvements.” So on February 13, 1819, New York congressman James Tallmadge rose in the House to add an amendment to the Missouri statehood bill that would bar the further importation of slaves into Missouri and emancipate any slave living in Missouri who reached the age of twenty-five.

2

Southern congressional delegations erupted in rage and panic. Not only was Missouri the first of the Louisiana Purchase territories to be added to the Union, but it also represented the only direct highway that the South possessed to lands further west. The land President Jefferson had purchased lay within a rough triangle, with the long side running from a point on the north Pacific coast in Oregon to Louisiana’s border with the old Spanish empire, and the great bulk of the area lying along the United States’ northern boundary with British Canada. Northern settlers could expand straight westward, across the Mississippi River, without being crammed together, but Southern settlers moving west were forced into the narrow lower corner of the triangle, against the border of Spanish Texas. Unless Southerners and slavery were allowed to expand equally into the Louisiana Purchase territories with Northerners, then the South could hope to develop only one or two future slave states. In short order, their alarm turned into threats of disunion and demands for assurance.

Tallmadge’s amendment, warned Thomas W. Cobb of Georgia, was full of “effects destructive of the peace and harmony of the Union… They were kindling a fire which all the waters of the ocean could extinguish. It could be extinguished only in oceans of blood.”

3

Nevertheless, the Tallmadge restrictions passed the House, 78 to 66, with representatives voting along virtually exclusively sectional North-South lines, and only the phalanx of Southern senators in the Senate (and five free-state allies) killed the

amended Missouri bill there. The House sent the amendments back to the Senate again, and at that point, in March 1819, Congress adjourned and left matters hanging.

The brief pause the intersession brought did nothing to allay the fears of onlookers. For the first time, slavery and sectionalism had reared their heads in Congress as a matter of national debate, and almost immediately Congress had divided along sectional lines. “This momentous question, like a fire-bell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror,” wrote an aging Thomas Jefferson. “I considered it at once the knell of the Union.”

4

To Jefferson’s relief, a solution quickly appeared in the form of Maine and Henry Clay. By the time Congress had settled back into Washington, another petition for admission to the Union had been received from Maine, which had been governed since colonial times as a province of Massachusetts. Henry Clay, then the Speaker of the House of Representatives, proposed to damp down the anxieties about upsetting the sectional balance in Congress by simultaneously admitting Missouri (as a slave state) and Maine (as a free state) to the Union. For the future, Clay called for the division of the Louisiana Purchase into two zones along the latitude line of 36° 30′ (the southern boundary line of Missouri), with the northern zone forever reserved for “free” settlement only and the southern zone left open to the extension of slavery. Adroitly sidestepping the partisans of both sections, Clay maneuvered the legislation through the House and greased its way through a joint House-Senate reconciliation committee to the desk of President James Monroe, who signed it on March 6, 1820.

5

The Missouri Compromise made the reputation of Henry Clay as a national reconciler and champion of the Union, and the 36°30′ line became the mutually agreed line of settlement that was supposed to squelch the need for any further antagonistic debates over the extension of slavery. It is difficult, looking back on the Missouri Compromise, to see just what advantages slaveholders believed they had won, since the available Louisiana Purchase territory lying south of the 36°30′ line was actually fairly minimal (only one other slave state, Arkansas, would ever be organized from it). Most of the recently acquired territory lay north of 36°30′, and even then it was by no means certain in the 1820s that the Canadian border was so permanently fixed that the United States could not expand further north. Great Britain and the United States had agreed to mutually govern the Oregon territory after 1812, and the Oregon boundaries then ran as far north as Russian-owned Alaska. With the right use of bluster and bluff on the British, the limits on free settlement above 36°30 ′ could be made almost unlimited. The South’s acquiescence in the 36°30′ agreement makes sense only if it had become fairly widely assumed by 1820 that the United States would also apply some bluff, bluster, and expansion to the Spanish territory that lay south of the Louisiana Purchase boundary, in Texas.