End Procrastination Now! (5 page)

Read End Procrastination Now! Online

Authors: William D. Knaus

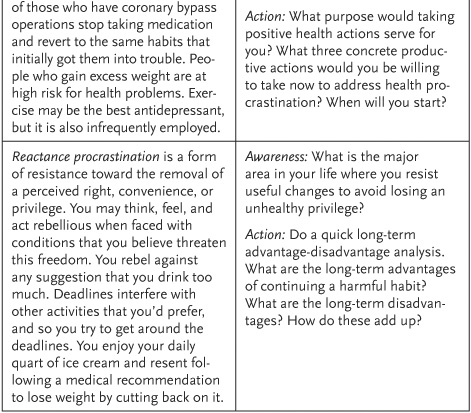

If procrastination interferes with a productive long-term work process, a chart reminder may help you keep perspective on the purpose, deadline, timeline, and procrastination risk factor:

Remember, being aware and cognizant of your procrastination habit is the first step in our three-pronged cognitive, emotive, and behavioral approach to defeat procrastination. Reminders can be helpful. Human memory is fallible. Some delays are due to forget-fulness. You can meet some deadlines automatically with mechanical processes, like automatic payments to utility companies and mortgage holders, that eliminate work. This is also an efficient thing to do. You can use tickler files, calendar notations, iPhones, PDAs, and your cell phone to remind you of important dates.

Deadline procrastination is just the tip of the procrastination iceberg. A bigger and more serious challenge may involve personal procrastination. Personal procrastination is habitually putting off

personally relevant activities, such as facing a needless inhibiting fear. You stick with a stressful job that you want to ditch. You feel timid, and you promise yourself that you'll take an assertiveness class someday. Instead of engaging in self-improvement activities, you watch TV and read tabloid magazines.

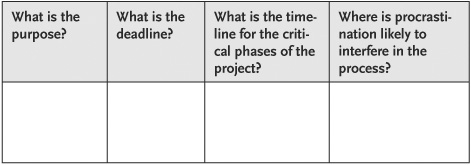

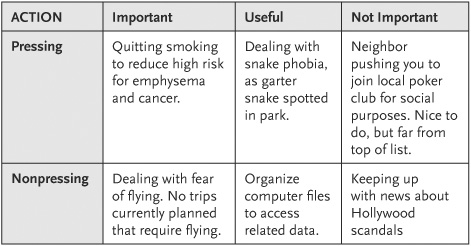

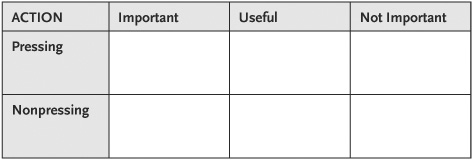

Because self-development activities are just about you, and because they are open-ended with an indefinite start date, this may not seem like procrastination. However, it meets the definition. The following chart is a classic framework for identifying your top self-development priority. The process involves defining your most pressing and important self-development goal or priority and other activities that are worth pursuing. Engaging in activities that are not important and nonpressing before all the activities above them are done may waste your time and resources. If you emphasize not important and nonpressing activities over your number one priority, you're procrastinating by using the bottom-drawer activities as diversions. For example, if you face a health risk and you read Hollywood scandal magazines in lieu of taking steps to stop smoking, you need to think about what you're doing. The following chart is an example.

Now it's your turn to define what are the most pressing and important things for you to do.

Omissions.

What you omit doing may be a prime area of personal procrastination. Dick was retired and spent a great deal of his time complaining. He complained about his woman friend and how her ongoing misery and physical complaints affected his mood. He complained about his breakfast group, whom he saw as the cold blanket squad who complained about their aches and pains and the importance of maintaining the status quo. He complained about lost opportunities and the hassles of life. What did these complaints have in common? They were all diversions.

Dick's pressing and important and nonpressing and not important self-development chart helped him isolate several areas of procrastination. First and foremost, he wanted to learn how to do teleconferencing on his computer so that he could keep in direct contact with his children and grandchildren. He wanted to visit art centers, travel, and study politics. His complaints covered up what he did with his time, which was mostly sleeping during the daytime and watching television at night. Once we established his priorities and identified the futility of complaining, then Dick started to work on his personal development challenges, which were no longer mysterious.

Simple procrastination is a default procrastination style in which you resist and recoil from any uncomplicated activity that you find mildly inconvenient or unpleasant. This may start with a momentary hesitation that, unless it is quickly overridden by a productive

action, may trigger a procrastination default reaction. This hesitation process may have to do with the way the brain works.

The brain may be wired to promote a

later

factor, or an automatic slowing in decision making: the time it takes the brain to voluntarily react to a sensory signal is longer than expected. This may be a result of decision-making and delay issues caused by your higher mental processes having difficulty understanding the signals from lower brain functions. The potential conflict between lower brain processes and cognitive decision-making processes may partially explain how a simple procrastination default reaction starts. If you have a discomfort sensitivity triggered by this conflict, and then you extend the delay to the level of procrastination, the

later

factor suggests a possible mechanism. But whether this is the real mechanism or the reaction is caused by something else, the solution remains the same. You have to act to override this biological resistance.

When procrastination includes coexisting conditions, it's complex. Complex procrastination is the kind of procrastination that is accompanied by other factors, such as self-doubts or perfectionism. Complex procrastination is a laminated variety. You can separate the layers and address each as a subissue. However, the layers tend to be interconnected, so by addressing one layer, you may weaken the connection with the others. For example, let's say you have an urge to engage in diversionary activities. You switch to doing something trivial, perhaps something more costly. You need to pay a bill, but instead, you go to a casino to gamble. You then try to forget your new gambling debts by turning on the TV.

When you face and overcome coexisting conditions, your goal of cutting back on procrastination doesn't go away. You may have eliminated one of the complex layers; however, procrastination often has a life of its own and goes on as it did before. You still have to deal with your procrastination habit if you want to free

yourself from this burden by changing procrastination thinking, developing emotional tolerance, and behaviorally pursuing productive goals.

Procrastination can be a symptom, a defense, a problem habit, or a combination of these general conditions. It can be a

symptom

of a complex form of procrastination, such as worrying about worry and then putting off learning cognitive coping skills to defuse the worry. Busywork can be a symptom of underlying tension for a problem that you want to avoid. This busyness is a kind of behavioral diversion, which is as productive as racing down a dead-end street.

A procrastination symptom can be especially helpful when it provides cues about an omission that needs recognizing and correcting. For example, the English naturalist Charles Darwin put off his medical studies and eventually came up with a theory of evolution by following his real passion. His

symptom

was his distraction from his medical school studies. Let's say your family persuades you to run the family sporting goods store. You have limited interest in managing the store, but you do so out of duty. Procrastination surfaces when it comes time to order new goods, keep up with paperwork, and deal with personnel matters, but you are quick and efficient in making better use of existing shelf space, creating an attractive façade, and landscaping, because what you really want to do is study architecture. What you emphasize in your work is a testament to your personal interest.

Procrastination can be a

defense

against conditions, such as fear of failure, failure anxiety, and fear of blame. If you tend to think in a perfectionistic way and you believe that you cannot succeed at the level at which you think that you should, this may trigger procrastination by causing you to exert only halfhearted efforts or to decide to do something else altogether. If you focus on the horrors

of failure, you may omit looking at a probable mechanism, such as perfectionist beliefs. Fear of success is another form of failure anxiety that can have the same impact as fear of failure. You believe that if you succeed, the pressure for you to do more will increase. In this frame of mind, it is easier to delay now than to risk failure later. You have other ways to construe these possibilities. Putting off thinking about these evaluative fears, and taking possible countermeasures, is a form of

conceptual procrastination

.

You can gain control over the causes of procrastination by addressing them. However, an automatic procrastination habit may remain, and you may continue to have an automatic urge to procrastinate.

Habits, even procrastination habits, may operate blindly when they serve no useful purpose. To respond to an automatic procrastination habit, plan on overpracticing your counter-procrastination strategy to weaken the strength of this automatic habit.

Procrastination is normally a complex problem process. Separating procrastination into the three categories of symptom, defense, and problem habit gives you a way to frame what is going on when you procrastinate. A good assessment for complex procrastination can point to change techniques that you may find useful. When you target potential underlying mechanisms for procrastination, you can more accurately target corrective efforts that fit the problem or recognize potentially effective actions through your own readings and research.

Procrastination comes about for different reasons. Like clothing, it comes in different styles. If you know your procrastination style(s), you can mate your corrective efforts to it. This is a big benefit. When you carefully target your corrective actions, you are less likely to go down dead-end streets or invest time in diversions that you may mistake for interventions. Lying on an analyst's couch to free-associate about early childhood issues about procrastination can be a diversion.

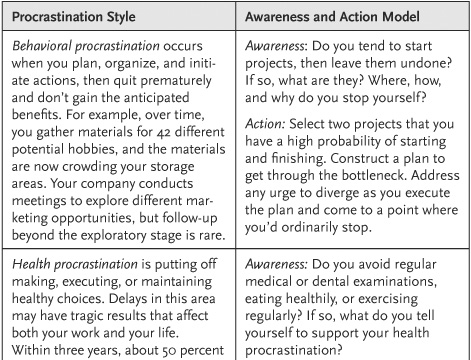

Table 1.1

describes a sample of procrastination styles and corrective actions.

TABLE 1.1

Procrastination Styles and Corrective Actions