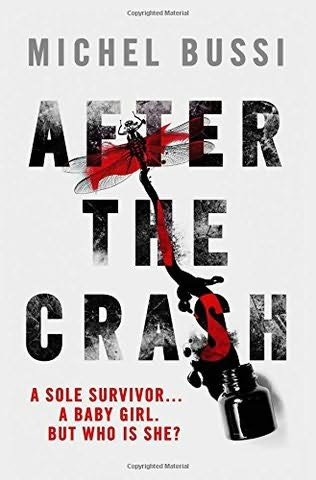

After the Crash

Authors: Michel Bussi

Translated from the French by Sam Taylor

First published in Great Britain in 2015

by Weidenfeld & Nicolson

An imprint of the Orion Publishing Group

Orion House, 5 Upper St Martin’s Lane, London wc2h 9ea

First published in French as

Un avion sans elle

by Presses de la Cité,

a department of Place des Editeurs, Paris.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Copyright © Presses de la Cité, a department of Place des Editeurs 2012

English translation copyright © Sam Taylor 2015

The rights of Michel Bussi and Sam Taylor, to be identified as

the author and translator of this work respectively, have been asserted in

accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

as part of the Burgess programme.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be

reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted,

in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior

permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher.

actual persons living or dead is purely coincidental.

978 0 297 87142 2 (cased)

978 0 297 87143 9 (export trade paperback)

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library

Typeset by Input Data Services Ltd, Bridgwater, Somerset

Printed and bound by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

The Orion Publishing Group’s policy is to use papers that are

natural, renewable and recyclable products and made from wood

grown in sustainable forests. The logging and manufacturing

processes are expected to conform to the environmental

regulations of the country of origin.

born with this story

The Airbus 5403, flying from Istanbul to Paris, suddenly plummeted. In a dive lasting less than ten seconds, the plane sank over

three thousand feet, before stabilising once again. Most of the

passengers had been asleep. They woke abruptly, with the terrifying

sensation that they had nodded off while strapped to a rollercoaster.

Izel was woken not by the turbulence, but by the screaming.

After nearly three years spent travelling the world with Turkish

Airlines, she was used to a few jolts. She had been on a break,

asleep for less than twenty minutes, and had scarcely opened her

eyes when her colleague Meliha thrust her aged, fleshy bosom

towards her.

‘Izel? Izel? Hurry up! This is serious. There’s a big storm outside.

Zero visibility, according to the captain. You take one aisle and I’ll

take the other.’

Izel’s face bore the weary expression of an experienced air hostess

who wasn’t about to panic over such a small thing. She got up from

her seat, adjusted her suit, pulling slightly at the hem of her skirt,

then moved towards the right-hand aisle.

The passengers were no longer screaming, and they looked more

surprised than worried as the aeroplane continued to pitch. Izel went

from one person to the next, calmly reassuring them: ‘Everything’s

fine. Don’t worry. We’re just going through a little snowstorm over

the Jura mountains. We’ll be in Paris in less than an hour.’

Izel’s smile wasn’t forced. Her mind was already wandering

towards Paris. She would stay there for three days, until Christmas,

and she was giddy with excitement at the prospect.

She addressed her words of comfort in turn to a ten-year-old boy

holding tightly to his grandmother’s hand, a handsome young businessman with a rumpled shirt, a Turkish woman wearing a veil, and

an old man curled up fearfully with his hands between his knees.

He shot her an imploring look.

Izel was calmly proceeding down the aisle when the Airbus

lurched sideways again. A few people screamed. ‘When do we start

doing the loop-the-loop?’ shouted a young man sitting to her right,

who was holding a Walkman, his voice full of false cheer.

A trickle of nervous laughter was drowned out almost immediately by the screams of a young baby. The child was lying in a

carrycot just a few feet in front of Izel – a little girl, only a few

months old, wearing a white dress with orange flowers under a knitted beige jumper.

The mother, sitting next to the baby, was unbuckling her belt so

she could lean over to her daughter.

‘No, madame,’ Izel insisted. ‘You must keep your seatbelt on. It’s

very important . . .’

The woman did not even bother turning around, never mind

replying to the air hostess. Her long hair fell over the carrycot. The

baby screamed even louder. Izel, unsure what to do, moved towards

them.

The plane plunged again. Three seconds, maybe another 3,000

feet.

There were a few brief screams, but most of the passengers were

silent. Dumbstruck. They knew now that the aeroplane’s movements were not merely due to bad weather. Jolted by the dive,

Izel fell sideways. Her elbow hit the Walkman, smashing it into

the young guy’s chest. She straightened up again immediately, not

even taking the time to apologise. In front of her, the three-monthold girl was still crying. Her mother was leaning over her again,

unbuckling the child’s seatbelt.

‘No, madame! No . . .’

Cursing, Izel tugged her skirt back down over her laddered

tights. What a nightmare. She would have earned those three days

of pleasure in Paris . . .

Everything happened very fast after that.

For a brief moment, Izel thought she could hear another baby

crying, like an echo, somewhere else on the aeroplane, further off

to her left. The Walkman guy’s hand brushed her nylon-covered

thighs. The old Turkish man had put one arm around his veiled

wife’s shoulder and was holding the other one up, as if begging Izel

to do something. The baby’s mother had stood up and was reaching over to pick up her daughter, freed now from the straps of the

carrycot.

These were the last things Izel saw before the Airbus smashed

into the mountainside.

The collision propelled Izel thirty feet across the floor, into the

emergency exit. Her two shapely legs were twisted like those of a

plastic doll in the hands of a sadistic child; her slender chest was

crushed against metal; her left temple exploded against the corner

of the door.

Izel was killed instantly. In that sense, she was luckier than most.

She did not see the lights go out. She did not see the aeroplane

being mangled and squashed like a tin can as it crashed into the

forest, the trees sacrificing themselves one by one as the Airbus

gradually slowed.

And, when everything had finally stopped, she did not detect the

spreading smell of kerosene. She felt no pain when the explosion

ripped apart her body, along with those of the other twenty-three

passengers who were closest to the blast.

one hundred and forty-five survivors.

Eighteen Years Later

1

29 September, 1998, 11.40 p.m.

Now you know everything

.

Crédule Grand-Duc lifted his pen and stared into the clear

water at the base of the large vivarium just in front of him. For

a few moments, his eyes followed the despairing flight of the

Harlequin dragonfly that had cost him almost 2,500 francs less

than three weeks ago. A rare species, one of the world’s largest dragonflies, an exact replica of its prehistoric ancestor.

The huge insect flew from one glass wall to another, through

a frenzied swarm of dozens of other dragonflies. Prisoners.

Trapped.

Pen touched paper once again. Crédule Grand-Duc’s hand shook

nervously as he wrote.

In this notebook, I have reviewed all the clues, all the leads, all the

theories I have found in eighteen years of investigation. It is all here, in

these hundred or so pages. If you have read them carefully, you will now

know as much as I do. Perhaps you will be more perceptive than me?

Perhaps you will find something I have missed? The key to the mystery,

if one exists. Perhaps . . .

For me, it’s over.

The pen hesitated again, and was held trembling just an inch

above the paper. Crédule Grand-Duc’s blue eyes stared emptily into

the still waters of the vivarium, then turned their gaze towards the

fireplace where large flames were devouring a tangle of newspapers,

files and cardboard archive boxes. Finally, he looked down again

and continued.

It would be an exaggeration to say that I have no regrets, but I have

done my best.

Crédule Grand-Duc stared at this last line for a long time, then

slowly closed the pale green notebook.

He placed the pen in a pot on the desk, and stuck a yellow Post-it

note to the cover of the notebook. Then he picked up a felt tip and

wrote on the Post-it, in large letters,

for Lylie

. He pushed the notebook to the edge of the desk and stood up.

Grand-Duc’s gaze lingered for a few moments on the copper

plaque in front of him: CRÉDULE GRAND-DUC, PRIVATE DETECTIVE. He smiled ironically. Everybody called him

Grand-Duc nowadays, and they had done for some time. Nobody

– apart from Emilie and Marc Vitral – used his ludicrous first name.

Anyway, that was before, when they were younger. An eternity ago.

Grand-Duc walked towards the kitchen. He took one last look at

the grey, stainless-steel sink, the white octagonal tiles on the floor,

and the pale wood cupboards, their doors closed. Everything was

in perfect order, clean and tidy; every trace of his previous life had

been carefully wiped away, as if this were a rented house that had

to be returned to its owner. Grand-Duc was a meticulous man

and always would be, until his dying breath. He knew that. That

explained many things. Everything, in fact.

He turned and walked back towards the fireplace until he could

feel the heat on his hands. He leaned down and threw two archive

boxes into the flames, then stepped back to avoid the shower of

sparks.

A dead end.

He had devoted thousands of hours to this case, examining each

clue in the most minute detail. All those clues, those notes, all that

research was now going up in smoke. Every trace of this investigation would disappear in the space of a few hours.

Eighteen years of work for nothing. His whole life was summarised in this

auto-da-fé

, to which he was the only witness.

In fourteen minutes, Lylie would be eighteen years old, officially

at least . . . Who was she? Even now, he still couldn’t be certain. It

was a one-in-two chance, just as it had been on that very first day.

Heads or tails.

He had failed. Mathilde de Carville had spent a fortune –

eighteen years’ worth of salary – for nothing.

Grand-Duc returned to the desk and poured himself another

glass of Vin Jaune. From the special reserve of Monique Genevez,

aged for fifteen years: this was, perhaps, the single good memory he

had retained from this investigation. He smiled as he brought the

glass of wine to his lips. A far cry from the caricature of the ageing

alcoholic detective, Grand-Duc was more the type of man to dip

sparingly into his wine cellar, and only on special occasions. Lylie’s

birthday, tonight, was a very special occasion. It also marked the

final minutes of his life.

The detective drained the glass of wine in a single mouthful.

This was one of the few sensations he would miss: the inimitable

taste of this distinctive yellow wine burning deliciously as it moved

through his body, allowing him to forget for a moment this obsession, the unsolvable mystery to which he had devoted his life.

Grand-Duc put the glass back on the desk and picked up the pale

green notebook, wondering whether to open it one last time. He

looked at the yellow Post-it:

for Lylie

.

This was what would remain: this notebook, these pages, written

over the last few days . . . For Lylie, for Marc, for Mathilde de Carville, for Nicole Vitral, for the police and the lawyers, and whoever

else wished to explore this endless hall of mirrors.

It was a spellbinding read, without a doubt. A masterpiece. A

thrilling mystery to take your breath away. And it was all there . . .

except for the end.

He had written a thriller that was missing its final page, a whodunit in which the last five lines had been erased.

Future readers would probably think themselves cleverer than

him. They would undoubtedly believe that they could succeed

where he had failed, that they could find the solution.

For many years he had believed the same thing. He had always

felt certain that proof must exist somewhere, that the equation

could be resolved. It was a feeling, only a feeling, but it wouldn’t

go away . . . That certainty had been what had driven him on until

this deadline: today, Lylie’s eighteenth birthday. But perhaps it was

only his subconscious that had kept this illusion alive, to prevent

him from falling into utter despair. It would have been so cruel to

have spent all those years searching for the key to a problem that

had no solution.

The detective re-read his final words:

I have done my best

.

Grand-Duc decided not to tidy up the empty bottle and the used

glass. The police and the forensics people examining his body a few

hours from now would not be worried about an unwashed glass.

His blood and his brains would be splashed in a thick puddle across

this mahogany desk and these polished floorboards. And should

his disappearance not be noticed for a while, which seemed highly

likely (who would miss him, after all?), it would be the stench of his

corpse that would alert the neighbours.

In the hearth, he noticed a scrap of cardboard that had escaped

the flames. He bent down and threw it into the fire.

Slowly, Grand-Duc moved towards the mahogany writing desk

that occupied the corner of the room facing the fireplace. He

opened the middle drawer and took his revolver from its leather

holster. It was a Mateba, in mint condition, its grey metal barrel

glimmering in the firelight. The detective’s hand probed more

deeply inside the desk and brought out three 38mm bullets. With

a practised movement he spun the cylinder and gently inserted the

bullets.

One would be enough, even given his relatively inebriated state,

even though he would probably tremble and hesitate. Because he

would undoubtedly manage to press the gun to his temple, hold

it firmly, and squeeze the trigger. He couldn’t miss, even with the

contents of a bottle of wine in his bloodstream.

He placed the revolver on the desk, opened the left-hand

drawer, and took out a newspaper: a very old and yellowed copy

of

Est Républicain

. This macabre set-piece had been in his mind for

months, a symbolic ritual that would help him to end it all, to rise

above the labyrinth for ever.