Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815 (108 page)

Read Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815 Online

Authors: Gordon S. Wood

Tags: ##genre

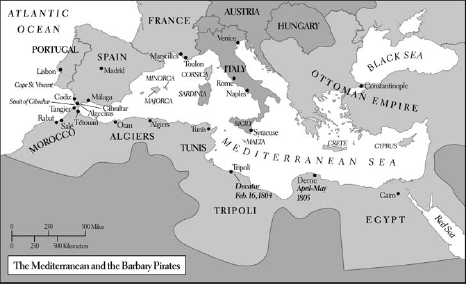

Throughout the 1780s Jefferson took a hard line against the Barbary States. He believed that they were so caught up in Islamic fatalism and Ottoman tyranny that their backward and indolent societies were beyond reform. He concluded that military force might be the only way to deal with these Muslim pirates. Offer them commercial treaties on the basis of equality and reciprocity, he said, and if they refuse and demand tribute, then “go to war with them.”

36

John Adams disagreed. He thought it would be cheaper to pay tribute to these North African states than to go to war with them. “For an Annual Interest of 30,000 pounds sterling then and perhaps for 15,000 or 10,000 we can have Peace, when a War would sink us annually ten times as much.” Jefferson countered with his own costs and calculations, including the creation of a “fleet of 150guns, the one half of which shall be in constant cruise,” all pointing to the advantages of fighting instead of paying tribute.

37

As these two ministers, one in Paris, the other in London, engaged in their debate over how best to deal with the Barbary States during the 1780s, they came to realize that the Confederation government was in no position either to go to war or to pay tributes.

Although the United States had ratified the liberal commercial treaty with Morocco in 1787, the Republic, even under the new federal Constitution, could not so easily deal with Algiers. In 1793, before the Washington administration could straighten out its policy toward the North African states and negotiate treaties with them, Algiers captured eleven more American ships and 105sailors, who were enslaved along with the earlier captured sailors. These seizures finally goaded Congress into action. In 1794 it voted one million dollars to purchase a peace and ransom the American prisoners and another million to build a naval force of six frigates, marking the beginning of the U.S. Navy under the Constitution.

The growing split between Federalists and Republicans in Congress complicated matters. Being no longer part of the administration, Jefferson

took a somewhat different view of the use of force. In fact, Jefferson’s advocacy of military might in any circumstances was always limited. Force was sometimes justified, but never if it resulted in an expansion of executive power and the sacrifice of republican values. He and other Republicans saw the Federalist military buildup against Algiers as a ploy to enhance presidential power at the expense of liberty. Congressman William Branch Giles of Virginia joined a number of other Republicans in declaring that navies were “very foolish things” that could only lead to heavy taxes and a bloated office-laden European-type government. Better than building frigates at a horrendous expense, the United States should forget about the Mediterranean and protect America’s coastline with some relatively inexpensive gunboats.

38

The Federalists controlled Congress, however, and pushed on with negotiations and the building of the six frigates, some of which ended up being used against the French in the Quasi-War. In 1795 the United States agreed to a humiliating treaty with Algiers that cost a million dollars in tributes and ransoms—an amount equal to 16 percent of federal revenue for the year. The government realized that the frigates would not be ready for several years and that the country stood to gain more from trade in the Mediterranean than the peace treaty cost. As soon as the treaty was ratified in 1796, Congress, confident that there would be no more seizures of American ships, cut back the number of warships to three. The government opened negotiations with Tunis and Tripoli, which had begun seizing American merchantmen. By the end of the decade the United States had treaties with all the Barbary States, but the cost was exorbitant, $1. 25million, over 20 percent of the federal government’s annual budget.

39

Unfortunately, the Barbary States regarded treaties simply as a means of extracting more tributes and presents, and the threats and demands for more money, and the humiliations, continued. Tripoli felt it was not being treated equally with Algiers, and early in March 1801 it declared war on the United States and began seizing American merchant ships.

President Jefferson came to office several weeks later apparently determined to change American policy. “Nothing will stop the eternal increase of demand from these pirates,” he told Secretary of State Madison in 1801, “but the presence of an armed force, and it will be more economical and more honorable to use the same means at once for suppressing their insolencies.”

40

Yet Jefferson’s strict construction of the Constitution made

him reluctant to engage the pirates offensively without a formal congressional declaration of war.

The Federalists, led by Hamilton in the press, pounced on this reluctance and forced the Republican Congress in 1802 to grant the president authority to use all means necessary to defeat the Tripolitan pirates. But the American blockade of Tripoli proved ineffective, mainly because the frigates could not maneuver in the shallow waters of Tripoli’s harbor. At the same time, Secretary of the Treasury Gallatin and the Republicans in the Congress were concerned with the rising cost of maintaining a naval force in the Mediterranean. They feared the possibility of “increasing taxes, encroaching government, temptations to offensive wars, &c,” more than the Barbary pirates.

41

Still, the administration was determined to act, even if only with a minimum expenditure of funds and what President Jefferson referred to as “the smallest force competent” to the mission.

42

In 1803 it appointed a new experienced commander for the Mediterranean squadron, Commodore Edward Preble, and sent several small gunboats to the Mediterranean. Before Preble could deploy his new force, the frigate USS

Philadelphia

and its three-hundred man crew, commanded by twenty-nine-year-old William Bainbridge, was accidentally beached in Tripoli’s harbor and had to surrender to an array of Tripolitan gunboats. The Pasha Yussef Karamanli of Tripoli set his initial demand for ransoming the newly captured American slaves at $1,690,000, more than the entire military budget of the United States.

43

United States naval officers were determined to do something. On February 16, 1804, twenty-five-year-old Lieutenant Stephen Decatur and his seventy-man crew entered Tripoli’s harbor under cover of darkness in a disguised vessel with the intention of burning the

Philadelphia

, thus preventing its being used as a Tripolitan raider. Since the American ship was deep in Tripoli’s harbor, surrounded by a dozen other armed vessels and under the castle’s heavy batteries, it was a dangerous, even foolhardy, mission; but it succeeded admirably, without the single loss of an American. This action, which Lord Nelson called “the most bold and daring act of the age,” turned Decatur into an instant celebrity and inspired extraordinary outbursts of American patriotism. At age twenty-five Decatur became the youngest man commissioned a captain in U.S. naval history.

44

Emboldened by this success, Jefferson sent an even larger squadron to the Mediterranean under the command of Preble’s senior, Samuel Barron, with the aim of punishing Tripoli. The expedition was to be paid for by a special tax on merchants trading in the Mediterranean, which the Federalists charged was an underhanded scheme to get the New England merchants to pay for the purchase of Louisiana. Following the advice of William Eaton, an ex-army captain and former consul to Tunis, the United States government authorized a loose alliance with the pasha of Tripoli’s elder brother, Hamet Karamanli, who hoped to regain the throne his younger brother Yussef had taken from him. According to one historian, this was the U.S. government’s “first overseas covert operation.”

45

In 1805 while the naval squadron besieged Tripoli, Eaton, who had an ambiguous status as an agent of the navy, and the pasha’s brother Hamet marched west from Egypt five hundred miles across the Libyan Desert with a motley force of five hundred Greek, Albanian, and Arab mercenaries and a handful of marines. Their goal was to join up with Captain Isaac Hull and three American cruisers at Derne, the strategic Tripolitan port east of Tripoli. After a successful bombardment, Eaton’s and Hull’s marines took the fort at Derne. (This action later inspired the refrain of

the U.S. Marine Corps hymn, “to the shores of Tripoli.”) Before Eaton could move his force against Tripoli, however, he learned that in June 1805 Tobias Lear, consul-general at Algiers, had signed a peace and commercial treaty with Tripoli ending the undeclared war.

Eaton felt betrayed by the U.S. government, and the war and what Eaton believed was its premature ending became caught up in partisan politics. The Federalists took every opportunity to chastise the Jefferson administration for its hesitancy in going to war against the Barbary States without a congressional declaration of war and for its ill-timed peace. Hamet did not get his throne back, but his family held in hostage was restored to him. The United States refused to pay any tribute to Tripoli, but it did pay a small ransom of sixty thousand dollars in order to get its imprisoned sailors released. Although the cynical European powers played down America’s victory in this Tripolitan war, believing quite correctly that the pirates would ignore any treaty and would soon be back in business, many Americans celebrated it as a vindication of their policy of spreading free trade around the world and as a great victory for liberty over tyranny.

At the same time, however, many Americans could not ignore the contradiction between the Barbary States’ enslaving seven hundred white sailors and their own country’s enslaving hundreds of thousands of black Africans. As early as 1790 Benjamin Franklin had satirized this hypocrisy, and poets and playwrights juxtaposed the two forms of servitude in their works. Connecticut-born and Dartmouth-educated William Eaton had at once seen the contradiction upon his arrival in Tunis in 1799 as American consul. “Barbary is hell—,” he wrote in his journal. “So, alas, is all America south of Pennsylvania; for oppression, and slavery, and misery, are there.”

46

B

UT THIS CONTEST

with the Barbary States was just a sideshow; the main act always involved America’s relationship with Great Britain. Getting the British, however, to sign a liberal free trade treaty similar to that with Tripoli was highly unlikely. Not only would such a treaty be difficult to achieve, but it was not something that Jefferson really wanted, as events in 1805–1806 revealed.

Jefferson knew that America’s prosperous trans-Atlantic carrying trade of French and Spanish colonial goods would require governmental

protection once war between Britain and France resumed, as it did in 1803. At first Britain seemed more or less willing to continue accepting the legal fiction of the “broken voyage” and America’s carrying trade continued to flourish even though occasional seizures of American ships took place.

Suddenly in the summer of 1805 the Royal Navy began seizing scores of American merchant ships that assumed they were complying with the principle of the “broken voyage.” Although Britain did not warn the United States of any change in policy, it had been contemplating tightening its treatment of the neutral carrying trade for some time. In the

Essex

decision in the spring of 1805 a British admiralty appeals court endorsed a change of policy and re-invoked the Rule of 1756 that had forbidden neutrals in time of war from trading within a mercantile empire closed to them in time of peace. By the new doctrine of the “continuous voyage,” American merchants would now have to prove that they actually intended their voyages from the belligerent ports to terminate in the United States; otherwise the enemy goods they carried were liable to seizure.

This single decision undercut the lucrative trade that had gone on for years with only minor interruptions. By September 1805 Secretary of State Madison reported that America’s merchants were “much alarmed” by the apparent change in British policy, for they had “several millions of property . . . afloat, subject to capture under the doctrine now enforced.” Insurance rates quadrupled, and American merchants faced heavy losses. During the latter half of 1805 merchants in Philadelphia complained of over a hundred seizures, valued at $500,000.

47

Many of the belligerents’ vice-admiralty courts, which passed on the legality of the seizures, were remarkably impartial, but not all. Some of the British prize courts in the West Indies were corrupt and incompetent, and many of their decisions that went against American ship owners were later reversed by the High Court of Appeals in England. Because of these reversals, the actual number of condemnations was perhaps no more than 10 or 20 percent of the number of seizures. James Monroe, America’s minister in London, told Secretary of State Madison in September 1805 that Britain “seeks to tranquillize us by dismissing our vessels in every case that she possibly can.” But the appeals took time, usually four or five years, all the while the seized American ships were tied up in British ports.

48