Delphi Complete Works of George Eliot (Illustrated) (560 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of George Eliot (Illustrated) Online

Authors: George Eliot

THE NEW SCHOOLFELLOW.

“Father,” said Tom one evening near the end of the holidays, “Uncle Glegg says Lawyer Wakem is going to send his son to Mr. Stelling. You won’t like me to go to school with Wakem’s son, will you, father?”

“It’s no matter for that, my boy,” said Mr. Tulliver; “don’t you learn anything bad of him, that’s all. The lad’s a poor deformed creatur. It’s a sign Wakem thinks high o’ Mr. Stelling, as he sends his son to him, and Wakem knows meal from bran, lawyer and rascal though he is.”

It was a cold, wet January day on which Tom went back to school. If he had not carried in his pocket a parcel of sugar-candy, there would have been no ray of pleasure to enliven the gloom.

“Well, Tulliver, we’re glad to see you again,” said Mr. Stelling heartily, on his arrival. “Take off your wrappings and come into the study till dinner. You’ll find a bright fire there, and a new companion.”

Tom felt in an uncomfortable flutter as he took off his woollen comforter and other wrappings. He had seen Philip Wakem at St. Ogg’s, but had always turned his eyes away from him as quickly as possible, for he knew that for several reasons his father hated the Wakem family with all his heart.

“Here is a new companion for you to shake hands with, Tulliver,” said Mr. Stelling on entering the study — “Master Philip Wakem. You already know something of each other, I imagine, for you are neighbours at home.”

Tom looked confused, while Philip rose and glanced at him timidly. Tom did not like to go up and put out his hand, and he was not prepared to say, “How do you do?” on so short a notice.

Mr. Stelling wisely turned away, and closed the door behind him. He knew that boys’ shyness only wears off in the absence of their elders.

Philip was at once too proud and too timid to walk towards Tom. He thought, or rather felt, that Tom did not like to look at him. So they remained without shaking hands or even speaking, while Tom went to the fire and warmed himself, every now and then casting glances at Philip, who seemed to be drawing absently first one object and then another on a piece of paper he had before him. What was he drawing? wondered Tom, after a spell of silence. He was quite warm now, and wanted something new to be going forward. Suddenly he walked across the hearth, and looked over Philip’s paper.

“Why, that’s a donkey with panniers, and a spaniel, and partridges in the corn!” he exclaimed. “Oh, my buttons! I wish I could draw like that. I’m to learn drawing this half. I wonder if I shall learn to make dogs and donkeys!”

“Oh, you can do them without learning,” said Philip; “I never learned drawing.”

“Never learned?” said Tom, in amazement. “Why, when I make dogs and horses, and those things, the heads and the legs won’t come right, though I can see how they ought to be very well. I can make houses, and all sorts of chimneys — chimneys going all down the wall, and windows in the roof, and all that. But I dare say I could do dogs and horses if I was to try more,” he added.

“Oh yes,” said Philip, “it’s very easy. You’ve only to look well at things, and draw them over and over again. What you do wrong once, you can alter the next time.”

“But haven’t you been taught anything?” said Tom.

“Yes,” said Philip, smiling; “I’ve been taught Latin, and Greek, and mathematics, and writing, and such things.”

“Oh, but, I say, you don’t like Latin, though, do you?” said Tom.

“Pretty well; I don’t care much about it,” said Philip. “But I’ve done with the grammar,” he added. “I don’t learn that any more.”

“Then you won’t have the same lessons as I shall?” said Tom, with a sense of disappointment.

“No; but I dare say I can help you. I shall be very glad to help you if I can.”

Tom did not say “Thank you,” for he was quite absorbed in the thought that Wakem’s son did not seem so spiteful a fellow as might have been expected.

“I say,” he said presently, “do you love your father?”

“Yes,” said Philip, colouring deeply; “don’t you love yours?”

“Oh yes; I only wanted to know,” said Tom, rather ashamed of himself, now he saw Philip colouring and looking uncomfortable.

“Shall you learn drawing now?” he said, by way of changing the subject.

“No,” said Philip. “My father wishes me to give all my time to other things now.”

“What! Latin, and Euclid, and those things?” said Tom.

“Yes,” said Philip, who had left off using his pencil, and was resting his head on one hand, while Tom was leaning forward on both elbows, and looking at the dog and the donkey.

“And you don’t mind that?” said Tom, with strong curiosity.

“No; I like to know what everybody else knows. I can study what I like by-and-by.”

“I can’t think why anybody should learn Latin,” said Tom. “It’s no good.”

“It’s part of the education of a gentleman,” said Philip. “All gentlemen learn the same things.”

“What! do you think Sir John Crake, the master of the harriers, knows Latin?” said Tom.

“He learnt it when he was a boy, of course,” said Philip. “But I dare say he’s forgotten it.”

“Oh, well, I can do that, then,” said Tom readily.

“Oh, I don’t mind Latin,” said Philip, unable to choke a laugh; “I can remember things easily. And there are some lessons I’m very fond of. I’m very fond of Greek history, and everything about the Greeks. I should like to have been a Greek and fought the Persians, and then have come home and written tragedies, or else have been listened to by everybody for my wisdom, like Socrates, and have died a grand death.”

“Why, were the Greeks great fighters?” said Tom, who saw a vista in this direction. “Is there anything like David, and Goliath, and Samson in the Greek history? Those are the only bits I like in the history of the Jews.”

“Oh, there are very fine stories of that sort about the Greeks — about the heroes of early times who killed the wild beasts, as Samson did. And in the

Odyssey

(that’s a beautiful poem) there’s a more wonderful giant than Goliath — Polypheme, who had only one eye in the middle of his forehead; and Ulysses, a little fellow, but very wise and cunning, got a red-hot pine tree and stuck it into this one eye, and made him roar like a thousand bulls.”

“Oh, what fun!” said Tom, jumping away from the table, and stamping first with one leg and then the other. “I say, can you tell me all about those stories? because I shan’t learn Greek, you know. Shall I?” he added, pausing in his stamping with a sudden alarm, lest the contrary might be possible. “Does every gentleman learn Greek? Will Mr. Stelling make me begin with it, do you think?”

“No, I should think not — very likely not,” said Philip. “But you may read those stories without knowing Greek. I’ve got them in English.”

“Oh, but I don’t like reading; I’d sooner have you tell them me — but only the fighting ones, you know. My sister Maggie is always wanting to tell me stories, but they’re stupid things. Girls’ stories always are. Can you tell a good many fighting stories?”

“Oh yes,” said Philip — “lots of them, besides the Greek stories. I can tell you about Richard Coeur-de-Lion and Saladin, and about William Wallace, and Robert Bruce, and James Douglas. I know no end.”

“You’re older than I am, aren’t you?” said Tom.

“Why, how old are you? I’m fifteen.”

“I’m only going in fourteen,” said Tom. “But I thrashed all the fellows at Jacobs’ — that’s where I was before I came here. And I beat ‘em all at bandy and climbing. And I wish Mr. Stelling would let us go fishing. I could show you how to fish. You could fish, couldn’t you? It’s only standing, and sitting still, you know.”

Philip winced under this allusion to his unfitness for active sports, and he answered almost crossly, —

“I can’t bear fishing. I think people look like fools sitting watching a line hour after hour, or else throwing and throwing, and catching nothing.”

“Ah, but you wouldn’t say they looked like fools when they landed a big pike, I can tell you,” said Tom. Wakem’s son, it was plain, had his disagreeable points, and must be kept in due check.

THE DUKE OF WELLINGTON.

As time went on Philip and Tom found many common interests, and became, on the whole, good comrades; but they had occasional tiffs, as was to be expected, and at one time had a serious difference which promised to be final.

This occurred shortly before Maggie’s second visit to Tom. She was going to a boarding school with Lucy, and wished to see Tom before setting out.

When Maggie came, she could not help looking with growing interest at the new schoolfellow, although he was the son of that wicked Lawyer Wakem who made her father so angry. She had arrived in the middle of school hours, and had sat by while Philip went through his lessons with Mr. Stelling.

Tom, some weeks before, had sent her word that Philip knew no end of stories — not stupid stories like hers; and she was convinced now that he must be very clever. She hoped he would think her rather clever too when she came to talk to him.

“I think Philip Wakem seems a nice boy, Tom,” she said, when they went out of the study together into the garden. “He couldn’t choose his father, you know; and I’ve read of very bad men who had good sons, as well as good parents who had bad children. And if Philip is good, I think we ought to be the more sorry for him because his father is not a good man. You like him, don’t you?”

“Oh, he’s a queer fellow,” said Tom curtly, “and he’s as sulky as can be with me, because I told him one day his father was a rogue. And I’d a right to tell him so, for it was true; and he began it, with calling me names. But you stop here by yourself a bit, Magsie, will you? I’ve got something I want to do upstairs.”

“Can’t I go too?” said Maggie, who, in this first day of meeting again, loved Tom’s very shadow.

“No; it’s something I’ll tell you about by-and-by, not yet,” said Tom, skipping away.

In the afternoon the boys were at their books in the study, preparing the morrow’s lessons, that they might have a holiday in the evening in honour of Maggie’s arrival. Tom was hanging over his Latin Grammar, and Philip, at the other end of the room, was busy with two volumes that excited Maggie’s curiosity; he did not look at all as if he were learning a lesson. She sat on a low stool at nearly a right angle with the two boys, watching first one and then the other.

“I say, Magsie,” said Tom at last, shutting his books, “I’ve done my lessons now. Come upstairs with me.”

“What is it?” said Maggie, when they were outside the door. “It isn’t a trick you’re going to play me, now?”

“No, no, Maggie,” said Tom, in his most coaxing tone; “it’s something you’ll like ever so.”

He put his arm round her neck, and she put hers round his waist, and, twined together in this way, they went upstairs.

“I say, Magsie, you must not tell anybody, you know,” said Tom, “else I shall get fifty lines.”

“Is it alive?” said Maggie, thinking that Tom kept a ferret.

“Oh, I shan’t tell you,” said he. “Now you go into that corner and hide your face while I reach it out,” he added, as he locked the bedroom door behind them. “I’ll tell you when to turn round. You mustn’t squeal out, you know.”

“Oh, but if you frighten me, I shall,” said Maggie, beginning to look rather serious.

“You won’t be frightened, you silly thing,” said Tom. “Go and hide your face, and mind you don’t peep.”

“Of course I shan’t peep,” said Maggie disdainfully; and she buried her face in the pillow like a person of strict honour.

But Tom looked round warily as he walked to the closet; then he stepped into the narrow space, and almost closed the door. Maggie kept her face buried until Tom called out, “Now, then, Magsie!”

Nothing but very careful study could have enabled Tom to present so striking a figure as he did to Maggie when she looked up. With some burnt cork he had made himself a pair of black eyebrows that met over his nose, and were matched by a blackness about the chin. He had wound a red handkerchief round his cloth cap to give it the air of a turban, and his red comforter across his breast as a scarf — an amount of red which, with the frown on his brow, and the firmness with which he grasped a real sword, as he held it with its point resting on the ground, made him look very fierce and bloodthirsty indeed.

Maggie looked bewildered for a moment, and Tom enjoyed that moment keenly; but in the next she laughed, clapped her hands together, and said, “O Tom, you’ve made yourself like Bluebeard at the show.”

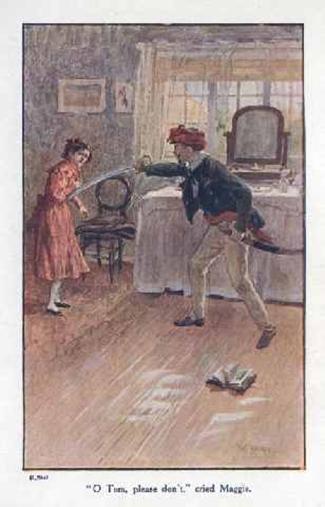

It was clear she had not been struck with the presence of the sword — it was not unsheathed. Her foolish mind required a more direct appeal to its sense of the terrible; and Tom prepared for his master-stroke. Frowning fiercely, he (carefully) drew the sword — a real one — from its sheath and pointed it at Maggie.

“O Tom, please don’t,” cried Maggie, in a tone of dread, shrinking away from him into the opposite corner; “I shall scream — I’m sure I shall! Oh, don’t! I wish I’d never come upstairs!”

“O Tom, please don’t,”, cried Maggie.

The corners of Tom’s mouth showed an inclination to a smile that was immediately checked. Slowly he let down the scabbard on the floor lest it should make too much noise, and then said sternly, —

“I’m the Duke of Wellington! March!” stamping forward with the right leg a little bent, and the sword still pointed towards Maggie, who, trembling, and with tear-filled eyes, got upon the bed, as the only means of widening the space between them.

Tom, happy in this spectator, even though it was only Maggie, proceeded to such an exhibition of the cut and thrust as would be expected of the Duke of Wellington.

“Tom, I will not bear it — I will scream,” said Maggie, at the first movement of the sword. “You’ll hurt yourself; you’ll cut your head off!”

“One — two,” said Tom firmly, though at “two” his wrist trembled a little. “Three” came more slowly, and with it the sword swung downwards, and Maggie gave a loud shriek. The sword had fallen with its edge on Tom’s foot, and in a moment after he had fallen too.

Maggie leaped from the bed, still shrieking, and soon there was a rush of footsteps towards the room. Mr. Stelling, from his upstairs study, was the first to enter. He found both the children on the floor. Tom had fainted, and Maggie was shaking him by the collar of his jacket, screaming, with wild eyes.

She thought he was dead, poor child! And yet she shook him, as if that would bring him back to life. In another minute she was sobbing with joy because Tom had opened his eyes. She couldn’t sorrow yet that he had hurt his foot; it seemed as if all happiness lay in his being alive.

In a very short time the wounded hero was put to bed, and a surgeon was fetched, who dressed the wound with a serious face which greatly impressed every one.