Delphi Complete Works of George Eliot (Illustrated) (558 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of George Eliot (Illustrated) Online

Authors: George Eliot

MAGGIE AND THE GIPSIES.

After Tom and Lucy had walked away, Maggie’s quick mind formed a plan which was not so simple as that of going home. No; she would run away and go to the gipsies, and Tom should never see her any more. She had been often told she was like a gipsy, and “half wild;” so now she would go and live in a little brown tent on the common.

The gipsies, she considered, would gladly receive her, and pay her much respect on account of her superior knowledge. She had once mentioned her views on this point to Tom, and suggested that he should stain his face brown, and they should run away together; but Tom rejected the scheme with contempt, observing that gipsies were thieves, and hardly got anything to eat, and had nothing to drive but a donkey. To-day, however, Maggie thought her misery had reached a pitch at which gipsydom was her only refuge, and she rose from her seat on the roots of the tree with the sense that this was a great crisis in her life.

She would run straight away till she came to Dunlow Common, where there would certainly be gipsies; and cruel Tom, and the rest of her relations who found fault with her, should never see her any more. She thought of her father as she ran along, but made up her mind that she would secretly send him a letter by a small gipsy, who would run away without telling where she was, and just let him know that she was well and happy, and always loved him very much.

Maggie soon got out of breath with running, but by the time that Tom got to the pond again she was at the distance of three long fields, and was on the edge of the lane leading to the highroad.

She presently passed through the gate into the lane, and she was soon aware, not without trembling, that there were two men coming along the lane in front of her.

She had not thought of meeting strangers; and, to her surprise, while she was dreading their scolding as a runaway, one of the men stopped, and in a half-whining, half-coaxing tone asked her if she had a copper to give a poor fellow.

Maggie had a sixpence in her pocket — her Uncle Glegg’s present — which she drew out and gave this “poor fellow” with a polite smile. “That’s the only money I’ve got,” she said. “Thank you, little miss,” said the man in a less grateful tone than Maggie expected, and she even saw that he smiled and winked at his companion.

She now went on, and turning through the first gate that was not locked, crept along by the hedgerows. She was used to wandering about the fields by herself, and was less timid there than on the highroad. Sometimes she had to climb over high gates, but that was a small evil; she was getting out of reach very fast, and she should probably soon come within sight of Dunlow Common. She hoped so, for she was getting rather tired and hungry. It was still broad daylight, yet it seemed to her that she had been walking a very great distance indeed, and it was really surprising that the common did not come in sight.

At last, however, the green fields came to an end, and Maggie found herself looking through the bars of a gate into a lane with a wide margin of grass on each side of it. She crept through the bars of the gate and walked on with a new spirit, and at the next bend in the lane Maggie actually saw the little black tent with the blue smoke rising before it which was to be her refuge. She even saw a tall female figure by the column of smoke — doubtless the gipsy-mother, who provided the tea and other groceries; it was astonishing to herself that she did not feel more delighted. But it was startling to find the gipsies in a lane after all, and not on a common — indeed, it was rather disappointing; for a mysterious common, where there were sand-pits to hide in, and one was out of everybody’s reach, had always made part of Maggie’s picture of gipsy life.

She went on, however, and before long a tall figure, who proved to be a young woman with a baby on her arm, walked slowly to meet her. Maggie looked up in the new face and thought that her Aunt Pullet and the rest were right when they called her a gipsy; for this face, with the bright dark eyes and the long hair, was really something like what she used to see in her own glass before she cut her hair off.

“My little lady, where are you going to?” the gipsy said.

It was delightful, and just what Maggie expected — the gipsy saw at once that she was a little lady.

“Not any farther,” said Maggie. “I’m come to stay with you, please.”

“That’s pritty; come, then. Why, what a nice little lady you are, to be sure!” said the gipsy, taking her by the hand. Maggie thought her very nice, but wished she had not been so dirty.

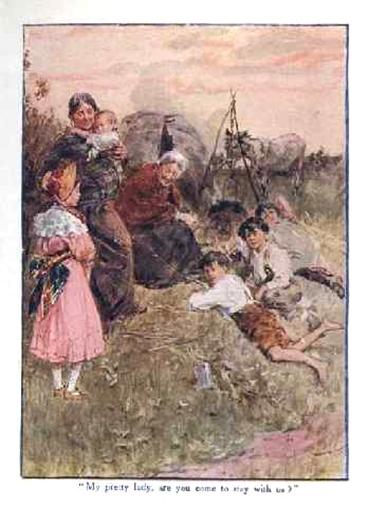

There was quite a group round the fire when they reached it. An old gipsy-woman was seated on the ground nursing her knees, and poking a skewer into the round kettle that sent forth an odorous steam; two small, shock-headed children were lying down resting on their elbows; and a donkey was bending his head over a tall girl, who, lying on her back, was scratching his nose and feeding him with a bite of excellent stolen hay.

The slanting sunlight fell kindly upon them, and the scene was really very pretty and comfortable, Maggie thought, only she hoped they would soon set out the tea-cups. It was a little confusing, though, that the young woman began to speak to the old one in a language which Maggie did not understand, while the tall girl who was feeding the donkey sat up and stared at her. At last the old woman said, —

“What, my pretty lady, are you come to stay with us? Sit ye down, and tell us where you come from.”

It was just like a story. Maggie liked to be called pretty lady and treated in this way. She sat down and said, —

“I’m come from home because I’m unhappy, and I mean to be a gipsy. I’ll live with you, if you like, and I can teach you a great many things.”

“Such a clever little lady,” said the woman with the baby, sitting down by Maggie, and allowing baby to crawl; “and such a pritty bonnet and frock,” she added, taking off Maggie’s bonnet and looking at it while she spoke to the old woman in the unknown language. The tall girl snatched the bonnet and put it on her own head hind-foremost with a grin; but Maggie was determined not to show that she cared about her bonnet.

“I don’t want to wear a bonnet,” she said; “I’d rather wear a red handkerchief, like yours” (looking at her friend by her side). “My hair was quite long till yesterday, when I cut it off; but I dare say it will grow again very soon.”

“Oh, what a nice little lady! — and rich, I’m sure,” said the old woman. “Didn’t you live in a beautiful house at home?”

“Yes, my home is pretty, and I’m very fond of the river, where we go fishing; but I’m often very unhappy. I should have liked to bring my books with me, but I came away in a hurry, you know. But I can tell you almost everything there is in my books, I’ve read them so many times, and that will amuse you. And I can tell you something about geography too — that’s about the world we live in — very useful and interesting. Did you ever hear about Columbus?”

“Is that where you live, my little lady?” said the old woman at the mention of Columbus.

“Oh no!” said Maggie, with some pity. “Columbus was a very wonderful man, who found out half the world; and they put chains on him and treated him very badly, you know — but perhaps it’s rather too long to tell before tea.

I want my tea so

.”

“Why, she’s hungry, poor little lady,” said the younger woman. “Give her some o’ the cold victual. — You’ve been walking a good way, I’ll be bound, my dear. Where’s your home?”

“It’s Dorlcote Mill — a good way off,” said Maggie. “My father is Mr. Tulliver; but we mustn’t let him know where I am, else he’ll fetch me home again. Where does the queen of the gipsies live?”

“What! do you want to go to her, my little lady?” said the younger woman.

“No,” said Maggie; “I’m only thinking that if she isn’t a very good queen you might be glad when she died, and you could choose another. If I was a queen, I’d be a very good queen, and kind to everybody.”

“Here’s a bit o’ nice victual, then,” said the old woman, handing to Maggie a lump of dry bread, which she had taken from a bag of scraps, and a piece of cold bacon.

“Thank you,” said Maggie, looking at the food without taking it; “but will you give me some bread and butter and tea instead? I don’t like bacon.”

“We’ve got no tea nor butter,” said the old woman with something like a scowl.

“Oh, a little bread and treacle would do,” said Maggie.

“We han’t got no treacle,” said the old woman crossly.

Meanwhile the tall girl gave a shrill cry, and presently there came running up a rough urchin about the age of Tom. He stared at Maggie, and she felt very lonely, and was quite sure she should begin to cry before long. But the springing tears were checked when two rough men came up, while a black cur ran barking up to Maggie, and threw her into a tremor of fear.

Maggie felt that it was impossible she should ever be queen of

these

people.

“This nice little lady’s come to live with us,” said the young woman. “Aren’t you glad?”

“Ay, very glad,” said the younger man, who was soon examining Maggie’s silver thimble and other small matters that had been taken from her pocket. He returned them all except the thimble to the younger woman, and she immediately restored them to Maggie’s pocket, while the men seated themselves, and began to attack the contents of the kettle — a stew of meat and potatoes — which had been taken off the fire and turned out into a yellow platter.

THE GIPSY QUEEN ABDICATES.

Maggie began to think that Tom must be right about the gipsies: they must certainly be thieves, unless the man meant to return her thimble by-and-by. All thieves, except Robin Hood, were wicked people.

The women now saw she was frightened.

“We’ve got nothing nice for a lady to eat,” said the old woman, in her coaxing tone. “And she’s so hungry, sweet little lady!”

“Here, my dear, try if you can eat a bit o’ this,” said the younger woman, handing some of the stew on a brown dish with an iron spoon to Maggie, who dared not refuse it, though fear had chased away her appetite. If her father would but come by in the gig and take her up! Or even if Jack the Giantkiller, or Mr. Greatheart, or St. George who slew the dragon on the half-pennies, would happen to pass that way!

“What! you don’t like the smell of it, my dear,” said the young woman, observing that Maggie did not even take a spoonful of the stew. “Try a bit — come.”

“No, thank you,” said Maggie, trying to smile in a friendly way. “I haven’t time, I think — it seems getting darker. I think I must go home now, and come again another day, and then I can bring you a basket with some jam-tarts and things.”

Maggie rose from her seat, when the old gipsy-woman said, “Stop a bit, stop a bit, little lady; we’ll take you home all safe when we’ve done supper. You shall ride home like a lady.”

Maggie sat down again, with little faith in this promise, though she presently saw the tall girl putting a bridle on the donkey and throwing a couple of bags on his back.

“Now, then, little missis,” said the younger man, rising and leading the donkey forward, “tell us where you live. What’s the name o’ the place?”

“Dorlcote Mill is my home,” said Maggie eagerly. “My father is Mr. Tulliver; he lives there.”

“What! a big mill a little way this side o’ St. Ogg’s?”

“Yes,” said Maggie. “Is it far off? I think I should like to walk there, if you please.”

“No, no, it’ll be getting dark; we must make haste. And the donkey’ll carry you as nice as can be — you’ll see.”

He lifted Maggie as he spoke, and set her on the donkey.

“Here’s your pretty bonnet,” said the younger woman, putting it on Maggie’s head. “And you’ll say we’ve been very good to you, won’t you, and what a nice little lady we said you was?”

“Oh yes, thank you,” said Maggie; “I’m very much obliged to you. But I wish you’d go with me too.”

“Ah, you’re fondest o’ me, aren’t you?” said the woman. “But I can’t go; you’ll go too fast for me.”

It now appeared that the man also was to be seated on the donkey, holding Maggie before him, and no nightmare had ever seemed to her more horrible. When the woman had patted her on the back, and said “good-bye,” the donkey, at a strong hint from the man’s stick, set off at a rapid walk along the lane towards the point Maggie had come from an hour ago.

Maggie was completely terrified at this ride on a short-paced donkey, with a gipsy behind her, who considered that he was earning half a crown. Two low thatched cottages — the only houses they passed in this lane — seemed to add to the dreariness. They had no windows to speak of, and the doors were closed. It was probable that they were inhabited by witches, and it was a relief to find that the donkey did not stop there.

At last — oh, sight of joy! — this lane, the longest in the world, was coming to an end, and was opening on a broad highroad, where there was actually a coach passing! And there was a finger-post at the corner. She had surely seen that finger-post before — “To St. Ogg’s, 2 miles.”

The gipsy really meant to take her home, then. He was probably a good man after all, and might have been rather hurt at the thought that she didn’t like coming with him alone. This idea became stronger as she felt more and more certain that she knew the road quite well, when, as they reached a cross-road, Maggie caught sight of some one coming on a horse which seemed familiar to her.

“Oh, stop, stop!” she cried out. “There’s my father! — O father, father!”

The sudden joy was almost painful, and before her father reached her she was sobbing. Great was Mr. Tulliver’s wonder, for he had been paying a visit to a married sister, and had not yet been home.

“Why, what’s the meaning o’ this?” he said, checking his horse, while Maggie slipped from the donkey and ran to her father’s stirrup.

“The little miss lost herself, I reckon,” said the gipsy. “She’d come to our tent at the far end o’ Dunlow Lane, and I was bringing her where she said her home was. It’s a good way to come arter being on the tramp all day.”

“Oh yes, father, he’s been very good to bring me home,” said Maggie — “a very kind, good man!”

“Here, then, my man,” said Mr. Tulliver, taking out five shillings. “It’s the best day’s work you ever did. I couldn’t afford to lose the little wench. Here, lift her up before me.”

“Why, Maggie, how’s this, how’s this?” he said, as they rode along, while she laid her head against her father and sobbed. “How came you to be rambling about and lose yourself?”

“O father,” sobbed Maggie, “I ran away because I was so unhappy — Tom was so angry with me. I couldn’t bear it.”

“Pooh, pooh!” said Mr. Tulliver soothingly; “you mustn’t think o’ running away from father. What ‘ud father do without his little wench?”

“Oh no, I never will again, father — never.”

Mr. Tulliver spoke his mind very strongly when he reached home that evening, and Maggie never heard one reproach from her mother, or one taunt from Tom, about running away to be queen of the gipsies.