Death in a Promised Land (15 page)

Read Death in a Promised Land Online

Authors: Scott Ellsworth

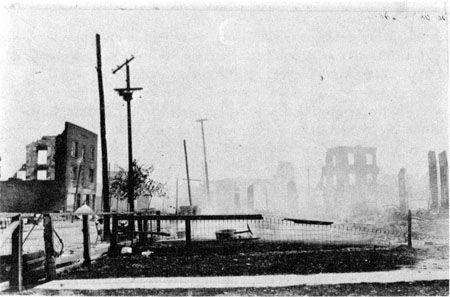

Looking toward “Deep Greenwood.”

Courtesy of Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Library

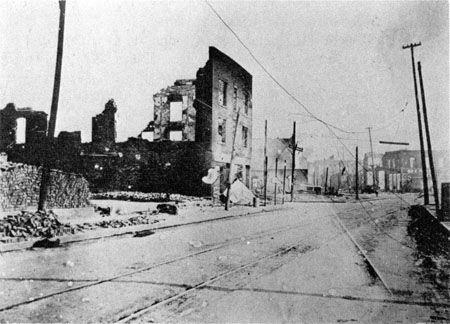

Part of the black business district.

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Tulsa Chamber of Commerce

By June 3, relief supplies were being given on a family basis, and on June 7, the Red Cross announced that “it would assist only those financially unable to bear the burden.” Efforts were made by the organization and other groups to secure employment for black Tulsans rendered jobless by the riot. The Red Cross made the homeless who were employed pay for meals, but for some time fed the unemployed and the ill for free. This latter group, along with women with infants, were given relief supplies, but the mode of distribution soon changed from actual handouts to “clothing and grocery permits.” Black women and some black children were given cloth and provided with sewing machines with which to make clothing and bedding. The Red Cross was also instrumental in securing tents for black Tulsans whose homes had been destroyed. Governor Robertson, who had refused the offer of fifty Black Cross nurses by the president of the Chicago chapter of the Universal Negro Improvement Association, also refused to consign some one hundred National Guard tents for use in Tulsa. Although, by the first week in July the Red Cross was feeding only those blacks who were ill, their relief work in Tulsa did not end until December of 1921. It should not be assumed that all black Tulsans accepted aid from the Red Cross, nor that the organization was not viewed without suspicion. Mary E. Jones Parrish, who was later loud in praise for the “Mother of the World,” at first avoided Red Cross workers.

19

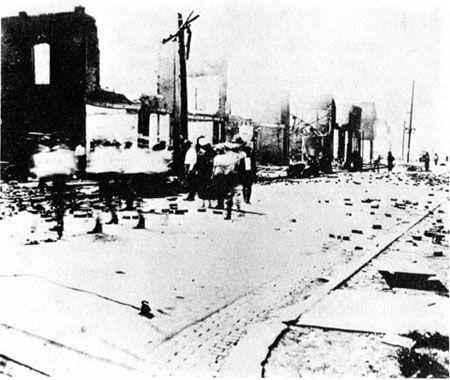

The remains of the “Negro Wall Street” looking north on Greenwood Avenue from Archer.

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Tulsa Chamber of Commerce

Some money and other donations also came into Tulsa from out of town. Civic organizations from various other Oklahoma towns and cities sent clothing and other articles. The NAACP initiated a nationwide campaign to raise money for the victims of the riot. It collected at least $1,900 for its “Tulsa Relief and Defense Fund,” and its contributions ranged from one dollar from a New Jersey woman, to nearly $350 from the Los Angeles Branch of the NAACP. In addition to sending money, the Colored Women’s Branch of the New York City YMCA also sent two barrels of clothing, which the express company shipped free of charge.

20

As important as these actions by non-Tulsans were, there was a much more powerful and ominous force working within Tulsa which shaped its post-riot history: the city’s official “relief” activities as carried out by the Executive Welfare Committee and its successor, the Reconstruction Committee. The former was organized, at the request of Adjutant General Barrett, on June 2 at a special meeting of the board of directors of the Tulsa Chamber of Commerce. It was authorized to “appoint such sub-committees as might be necessary in the rehabilitation work and in bringing Tulsa back to normalcy.”

21

Before this meeting adjourned, Alva J. Niles, president of the Chamber of Commerce, read a statement concerning the riot which he had given to the press. In it, Niles stated:

Leading business men are in hourly conference and a movement is now being organized, not only for the succor, protection and alleviation of the sufferings of the negroes, but to formulate a plan of reparation in order that homes may be re-built and families as nearly as possible rehabilitated. The sympathy of the citizenship of Tulsa in a great way has gone out to the unfortunate law abiding negroes who have become the victims of the action, and bad advice of some of the lawless leaders, and as quickly as possible rehabilitation will take place and reparation made....

Tulsa feels intensely humiliated and standing in the shadow of this great tragedy pledges its every effort to wiping out the stain at the earliest possible moment and punishing those guilty of bringing the disgrace and disaster to this city.

Niles ended his statement by citing Tulsa’s war effort accomplishments, such as the Liberty Loan drive, as evidence that the “city can be depended upon to make a proper restitution and to bring order out of chaos at the earliest possible moment.”

22

A similar attitude was expressed by L. J. Martin, chairman of the Executive Welfare Committee. Martin was quoted in the

Independent

as stating: “Tulsa can only redeem herself from the countrywide shame and humiliation in which she is today plunged by complete restitution of the destroyed black belt. The rest of the United States must know that the real citizenship of Tulsa weeps at this unspeakable crime and will make good the damage, so far as can be done, to the last penny.”

23

This was not, however, the course of action which the Executive Welfare Committee took, and in light of what this committee actually did do, few statements about the riot are as hideously ludicrous as these made by Niles and Martin. On June 4, there was a meeting between the Executive Welfare Committee—which, like the Chamber of Commerce, had no black members—and other white “relief” groups. They decided not to solicit any funds for aid, “but that any offers in the form of cash would be accepted by the Red Cross and used for relief work.” Furthermore, and most importantly, “it was decided not to accept any other kind of donation nor would any help, financial or otherwise, be accepted to reconstruct the Negro district.”

24

Thus, while the officials of the Tulsa Chamber of Commerce were telling the nation’s press that reparation and restitution would be made, they charted a directly opposite course, even to the point of refusing offers of aid for people whom they hardly represented. One Chamber of Commerce member stated that “numerous telegrams were received by the executive committee from various cities in the Union offering aid, but the policy was quickly adopted that this was strictly a Tulsa affair and that the work of restoration and charity would be taken care of by Tulsa people.” This supports a statement made by Walter White that outsiders made offers of money to be used in relief work in Tulsa—including a $1,000 offer of aid from the Chicago

Tribune

—but that the parties were told “in theatric fashion that the citizens of Tulsa ‘were to blame for the riot and that they themselves would bear the costs of restoration.’”

25

On June 14, Mayor Evans appointed a Reconstruction Committee, approved by the City Commission, to carry out his plans for the “reconstruction” of black Tulsa, and to direct the city’s official post-riot policies. The next day, the members of the Executive Welfare Committee tendered their resignations to the board of directors of the Chamber of Commerce, their authority in “relief” work having been negated by the action of the City Commission.

26

However, one week earlier, two actions occurred which provide yet another view of the “relief” intentions of the local white powers and elite.

The first was mentioned in the June 7 report of the Executive Welfare Committee, in which it informed the public that, under its direction, “the Real Estate Exchange was organized to list and appraise the value of properties in the burned area and to work out a plan of possible purchase and the conversion of the burned area into an industrial and wholesale district.” This plan received the support of certain white civic organizations, businessmen, and political elements, and the Executive Welfare Committee took some steps toward establishing a group to buy the land from black owners.

27

The other action of June 7, motivated by similar desires, was the passage of Fire Ordinance No. 2156 by the City Commission. Under its provisions, several blocks of the burned black district which had been partially, if not totally, destroyed were now made part of the “official” fire limits of the City of Tulsa. This was not an issue of small consequence to black Tulsans, nor was it by any means a gesture of kindness toward them, for any structure within the city’s “official” fire limits had to be constructed of concrete, brick, or steel, and had to be at least two stories high. The effect of the ordinance was to prevent some black Tulsans from rebuilding their burned homes where they had been. Walter White observed that the ordinance was passed “for the purpose of securing possession of the land at a low figure,” and that “white business men” had been trying to obtain this land for years.

28

That Mayor Evans particularly favored these actions is best evident in his June 14 message to the City Commission. “Let the negro settlement be placed farther to the north and east,” Evans stated, citing his belief that “a large portion of this district is well suited for industrial purposes than for residences.” The mayor of Tulsa also urged the commissioners to take action quickly: “We should immediately get in touch with all the railroads with a view to establishing a Union station on this ground. The location is ideal and all the railroads convenient.”

29

Whether or not the Executive Welfare Committee and Mayor Evans had been working in conjunction prior to this meeting of the City Commission, it is quite evident that they were basically expressing the same designs for black Tulsa.

Some of the directors of the Chamber of Commerce—some of whom had been members of the Executive Welfare Committee— eventually turned against these plans. On July 1, the Chamber’s board of directors approved a resolution of the city’s Reconstruction Committee that a union railway station project be explored, but omitted “the recommendation of any particular location for the terminal.” Two weeks later, a black man appeared before the board and informed them that under the present rulings it was not possible for black Tulsans to build on their own property. He also stated that “as winter is rapidly approaching it is necessary that the construction of homes begin at once.” After “considerable discussion,” the board of directors appointed a five-man committee to investigate the issue. Four days later, this special committee submitted a report which stated:

That the paramount issue at this time is the housing and rehabilitation of the negroes.

That while the Union Station project and industrial district may be desirable at some further time, the agitation of the same now is not germain

[sic]

to the issue.

That in order to enable the negro property owner to help himself he should be allowed to immediately house himself and family on his property.