Death in a Promised Land (11 page)

Read Death in a Promised Land Online

Authors: Scott Ellsworth

Efforts by some whites to limit the destructiveness of the riot failed. As the white rioters moved further north, they entered more of black Tulsa’s residential districts. At 9:30

A.M

., John P. Richards, the white principal of the Sequoyah School, called the police about the stretch of black homes along part of North Detroit Avenue, perhaps black Tulsa’s wealthiest neighborhood. He told the police that this area was still untouched by violence, and that a few police officers—if dispatched immediately—could protect this area from destruction. Richards stated that the police said they would send a few men, but they never came. Shortly after his call, a group of whites came to the area, looted, and set fire to each of these homes.

29

Calm amid the storm.

Courtesy of the Metropolltan Tulsa Chamber of Commerce

Black Tulsa engulfed by flames, June 1, 1921. A northerly view looking toward “Deep Greenwood” from across the Frisco railyards.

Courtesy of the McFarlin Library, University of Tulsa

The destruction of June 1, seen from probably the northeast, with either the Santa Fe or Midland Valley tracks in the foreground.

Courtesy of the Metropolltan Tulsa Chamber of Commerce

Looking west toward Greenwood. The Red Cross estimated that over one thousand homes were burned by the white rioters.

Courtesy of the McFarlin Llbrary, University of Tulsa

III

Adjutant General Barrett and the National Guard troops from Oklahoma City arrived in Tulsa by train at about 9:15

A.M

. By that time, much of the gunplay between blacks and whites had died down, though looting continued. Black Tulsa was burning. For many black citizens, there was literally no place to hide. Some fled the city and received rough treatment at the hands of whites in some of the smaller towns outside of Tulsa. Some white vigilantes even roamed affluent white neighborhoods to round up black live-in domestic workers. One carload of whites dragged a black corpse around the streets of downtown. And in the downtown area, as well as in some of the white neighborhoods, trucks loaded with corpses were observed by some residents. Sheriff McCullough slipped out of town with Dick Rowland at about eight o’clock.

30

When the National Guardsmen arrived, they did not immediately take to the streets. Barrett went to City Hall and set up his headquarters, while his troops prepared and ate breakfast. In light of the disorder in Tulsa, Barrett called Governor Robertson and requested that he decree martial law throughout the city. Robertson agreed, and martial law was declared at 11:29

A.M

. Barrett had circulars announcing the decree posted throughout the city.

31

Once activated, the guardsmen concentrated their efforts on aiding the fire department in their renewed efforts to control the city’s fires. They also began to imprison any black Tulsans who had not yet been interned. The guards took imprisoned blacks out of the hands of the “special deputies” and other groups of whites. Barrett ordered Mayor Evans to revoke all of these special commissions, which Evans did, claiming that many of the men who held them were the mob leaders themselves.

32

Throughout the day, many blacks were taken to the fairgrounds, as Convention Hall was full. Apparently some whites were also taken to this site, which was guarded by thirteen National Guardsmen. Whites were disarmed by guardsmen throughout the city, but were generally merely sent home. Sixty-five whites, however, were arrested by the troops, and a truckload of rifles was seized from one group of whites.

33

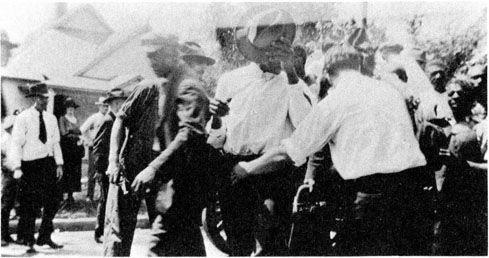

Armed whites searching blacks.

Courtesy of the McFarlin Library, University of Tulsa

En route to an internment center. Tulsa physician A. C. Jackson, who had been named by the Mayo brothers as “the most able Negro surgeon in America,” was murdered on one such march.

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Tulsa Chamber of Commerce

Whites collecting black prisoners

Courtesy of the Metropolltan Tulsa Chamber of Commerce

As is the case with many aspects of the riot, there is some confusion over the use of airplanes. During the violence, police took over private airplanes and flew over the city. After the riot, planes were sent out to observe any unusual activity in virtually every substantial black community in northeastern Oklahoma, purportedly because many white Tulsans feared a black counterattack. There is other evidence, however, on the subject of airplanes. Mary E. Jones Parrish, a black Tulsan who experienced the riot, passionately described those early morning hours:

After watching the men unload on First Street where we could see them from our windows, we heard such a buzzing noise that on running to the door to get a better view of what was going on, the sights our eyes beheld made our poor hearts stand still for a moment. There was a great shadow in the sky and upon a second look we discerned that this cloud was caused by fast approaching enemy aeroplanes. It then dawned upon us that the enemy had organized in the night and was invading our district the same as the Germans invaded France and Belgium. The firing of guns was renewed in quick succession. People were seen to flee from their burning homes, some with babes in their arms and leading crying and excited children by the hand; others, old and feeble, all fleeing to safety. Yet, seemingly, I could not leave. I walked as one in a horrible dream. By this time my little girl was up and dressed, but I made her lie on the dufold in order that bullets must penetrate it before reaching her. By this time a machine gun had been installed in the granary and was raining bullets down on our section.

Parrish’s account only implies that planes may have attacked the area, but the Chicago

Defender

reported directly that black neighborhoods in Tulsa were bombed from the air by a private plane equipped with dynamite.

34

After martial law was declared, violence generally ceased and some relief work began. The Tulsa race riot, one of the most devastating single incidents of racial violence in twentieth century America, was over within twenty-four hours of its inception. While most rioters returned to their homes, most of Tulsa’s black citizenry was imprisoned; over six thousand blacks were reported as being interned on the night of June 1. Others had fled the city. Upward of fifty people—both blacks and whites—were dead. Over one thousand homes and businesses—much of black Tulsa—lay in ruin, a smoldering monument to crushed dreams.

35