Dean and Me: A Love Story (17 page)

Read Dean and Me: A Love Story Online

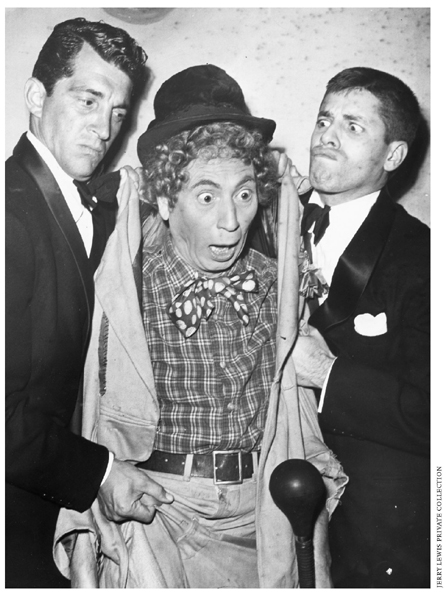

Authors: Jerry Lewis,James Kaplan

Tags: #Fiction, #Non-Fiction, #Music, #Humour, #Biography

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

THAT LOVELY TRIP REMINDS ME OF ANOTHER ONE: AT THE precise midpoint of our ten years together, in July of 1951, we played Grossinger’s in the Catskill Mountains.

Now, that might not sound so strange to you, but in 1951, the likelihood of such an engagement was not even a long-shot bet—no bookie would have taken your action.

Martin and Lewis in the Borscht Belt, even in the heyday of the Borscht Belt? Lewis, yes. Martin, no way!

By that summer, we had turned down Grossinger’s for three years straight, and we planned to keep turning them down. We always had something else going on, and the fit didn’t feel right.

But Paul Grossinger was a young man who didn’t know how to take “No” for an answer. He felt—no, he

knew

—that everything has a price. That was Paul’s way of thinking, and he was a nice, warm, and friendly man, and personally, I hoped we could do it just on account of his being a terrific guy.

So Paul’s agent called ours: “We want Martin and Lewis for an exclusive one-night show at Grossinger’s.” (

Exclusive

meaning that we could not play any other hotel up that way—as if we’d finish that show and dash off to Kutsher’s!) The agent went on to say, “We know how many times they’ve turned us down since 1948. They said no to $25,000 and no to $50,000, and they said no to $75,000! We now feel we have to go the last mile and make them an offer of $100,000 for the night.”

Our representative said, “Let me call you back.”

At this point, I, in my house in Las Vegas, whip out my handy inflation calculator and note that $100,000 in 1951 translates to approximately $733,462.38 in today’s dollars. Approximately.

These were not the kind of numbers offered by agents over the phone. Our representative hung up and got me at my office at Paramount. I said, “But we turned them down each time because we were either doing a film or were otherwise unavailable.”

“You know that, I know that, Dean knows that. But

they

don’t know that.”

I said, “Let me talk to Dean.”

I ran out of my office to Dean’s dressing room, just across the way. He was smoking a Camel, watching a rerun of some old movie, and waiting for Artie, the barber, to come and give him a haircut. I walked over and turned the set off.

“Hey, they were just about to show the murderer!” Dean yelled, getting out of his chair to turn the TV back on.

“Don’t bother!” I said. “I saw it! It was Henry Fonda.”

(Note: Henry Fonda never played a murderer in his entire career.)

“What’s so goddamn important, and why are you puffing like a tired racehorse?” he asked.

“Because,” I whispered, “Grossinger’s wants to give us

one hundred

thousand dollars

for

one show

. One night. The most money ever paid to anyone in the history of show business.... Including Frank, Bing, Caruso, and Mario Lanza.”

For one of the few times I can remember, Dean was hooked. “Tell me you’re joking,” he said. “Tell me I can’t really pick up fifty grand for doing one performance!”

“I’m telling you you can pick up a hundred grand for that one show, but I get half. So work it any way you want—just tell me to okay it!”

He jumped onto his couch and bounced up a couple of feet in the air. “What the hell are you still doing here?” he yelled. “Go and say yes!”

A Saturday night in the Catskill Mountains in the early 1950s was a lot like Times Square on New Year’s Eve. There was no other hotel like Grossinger’s. The dining room fed 1,600 people at a time (with two sittings, like a cruise ship), at big round tables seating twelve. Before that there were cocktails. There was milling, there was

shmoozing

, there was

kvelling

and yelling

.

There was

tummling

, by busboys who would grow up to be comedy headliners. In short, Jewish pandemonium! And tonight the pandemonium was compounded by our presence at Paul Grossinger’s table.

Watching Dean on this turf was priceless. All the little old ladies would come to the table and just flat-out kiss him on the face, rub his hair, pinch his cheeks.

And Dean was loving it. He was loving it, but I also recall that he

was

hungry, and anxious to get into the half-grapefruit already sitting in front of him, with a little American flag stuck in the center. There were also pickles and horseradish and rye bread—but no butter. Kosher is kosher. Dean picked up a slice of bread and scanned the entire table for butter. No one would say anything, so I told him: “Butter you get here for breakfast and maybe lunch, but not for a meat meal!”

Dean shouted, “Then I’ll eat what I need to eat to get some butter!” I glanced over at Paul Grossinger, who gave me a look as if to say, “No way!”

I crept around the table, knelt by Dean, and whispered the ground rules to him. “We just traveled three thousand miles,” he said. “You couldn’t tell me to buy butter?”

“And no milk,” I tell him. “And no cream.”

“So why do the Jews hate cows?”

Now we move forward four years to the spring of 1955. You may remember a friend of mine named Charlie Brown—the man, not the cartoon. Charlie and his wife Lillian were hotelkeepers who let me busboy and bunk at the Arthur, their Lakewood, New Jersey, resort, when I was just starting out. I had sweated through the earliest performances of my record act on their stage. In the interim, Charlie and Lily had moved their establishment to the Catskills, and now Brown’s, in Loch Sheldrake, New York, was one of the important hotels of the Jewish Alps.

So when Uncle Charlie called me and asked if Brown’s could host a gala premiere, in early June, for the thirteenth and latest Martin and Lewis movie,

You’re Never Too Young

, I was absolutely thrilled. Charlie was offering to pay for everything—transportation, accommodations, food, cocktail parties, and press receptions. He was even offering to permanently dedicate Brown’s newly constructed theater, the site of the proposed premiere, to Martin and Lewis, with a ribbon-cutting ceremony at the Dean Martin–Jerry Lewis Playhouse! It was irresistible.... I thought back to my early days at the Arthur Hotel in Lakewood, perspiring as I lip-synched to Frank Sinatra and Danny Kaye, then imagined myself returning to the Browns, a celebrity.

When I brought up the idea at a meeting of our production company, everyone there—Hal Wallis; director Norman Taurog; Paul Jones, line producer for York Productions, the company Dean and I had started; the Paramount head of publicity; and Jack Keller—found it equally irresistible. Wallis, in particular, was ecstatic at the idea of Charlie’s footing the entire bill. “Terrific deal!” he said. “Can’t go wrong! This oughta save us fifteen, twenty thousand bucks!”

Then I told Dean.

It was the following morning, and my partner did not look pleased. In fact, he gave me such a glare that the little hairs rose on the back of my neck. Suddenly, all the ill will that we’d sidestepped for months came flooding back. “You should have consulted me first,” Dean said.

I fought back feelings of panic—alone, he’s going to leave me all alone. But I could always act as tough as anyone, even Dean. “I’m consulting you now,” I told him. “Give me the word and we’ll do it. If not, we won’t.”

He took a long, slow breath. “Actually, Jerry, I really don’t care where we hold it.”

I took this to be tacit approval. (We hear what we want to hear.) And so I got right on the phone with Uncle Charlie, who went straight to work on the extensive preparations for the big event.

The night before our fifty-plus-person party was to get on the east-bound Super Chief, there was a knock on my office door at Paramount. It was Mack Gray.

Mack, aka Maxie Greenberg, was a onetime prizefighter who had worked as George Raft’s man Friday for twenty years. He’d been very much present at Raft’s pool party on our first night in Hollywood. When Raft couldn’t afford to keep him on anymore, Gray went to work in the exact same capacity for Dean. I always had a full staff buzzing around me; Dean mostly just had Mack. Mack was a gofer. If Dean needed a pack of cigarettes, or a girl driven home at seven A.M., Mack was his guy. He wasn’t the sharpest tool in the shed, but I liked him. Thought I did, anyway.

Now he was staring at me with that sad tough-guy’s face. “Your partner isn’t making the trip,” he said.

“Are you putting me on?” I said.

“Look, Jerry, I’m relaying this straight from Dean’s mouth. He said he’s tired. He’s going to take Jeanne on a trip to Hawaii. What else can I tell you?”

I felt like somebody had kicked me in the stomach. At the same time, some part of me couldn’t help but marvel at how Dean had once again avoided confrontation by sending Mack. He had also stuck it to me by bailing at the very last minute. It was all too symbolic—my partner and I were headed thousands of miles in opposite directions. I got on the train the next morning with my family and the rest of our large party and traveled east in a miserable rage, unable to explain my despair even to my nearest and dearest.

Meanwhile, before heading to Hawaii, Dean sat down with syndicated columnist Earl Wilson and fired another couple of shots across my bow: “I want a little TV show of my own, where I can sing more than two songs in an hour,” he told Wilson. “I’m about ten years older than the boy. He wants to direct. He loves work. So maybe he can direct and I can sing.”

Then Wilson asked him why he hadn’t gone east with me. “Outside of back east,” Dean said, “who knows about the Catskills?”

A trickle of blood had first leaked into the water when we had our troubles on

Three Ring Circus

, but the press was slightly more discreet in those days, and then the story of Martin and Lewis’s troubles died down.

Now, however, it was back again in full force, and there was a crowd of hungry reporters waiting for me when I got off the train at Penn Station on June 9. I was completely unprepared for their questions.

“Where’s Dean?” “Why didn’t your partner make the trip?” “Are you feuding?”

I must have looked like a man on his way to the gallows. “No comment” was all I came up with.

“Then where is he? Can you comment on that?”

“No. You’ll have to ask him.”

They were all yelling at once. “Have a heart! C’mon, Jerry, you’re not helping us!”

“If I commented, it wouldn’t help me.”

The drive north to the Catskills was more miserable with each passing mile. Route 17 was plastered with billboards announcing the appearance of Martin and Lewis at Brown’s Hotel. And when we pulled into the driveway of the resort, there were Uncle Charlie and Aunt Lil standing on the big front porch, beaming out into the light rain.

I was moved; I was terrified; I was mortified. I gripped Patti’s hand for dear life. “Momma, what am I going to tell them?”

“Whatever you think is best,” my brave wife said.

The clichés about show people are true: We

do

smile when we’re low. And the lower you feel, the bigger and broader a grin you need. We arrived on Friday afternoon, and from the moment I stepped out of the car until the premiere on Saturday night, I was completely in character as the kid half of Martin and Lewis, impersonating a bellhop, a busboy, a waiter; kibitzing with the guests. After the screening of

You’re Never Too

Young

, there was a two-hour show: Alan King performed, and my wife the former band singer directed a number, “He’s Funny That Way,” right to me. And then another King showed up—Sonny King, the guy who first introduced me to Dean! Sonny and I did a little shtick together. It all felt like a weird episode of

This Is Your Life

.

By the time the big show was over, I simply couldn’t take any more. The facade cracked. Another gang of reporters was waiting for me at the foot of the stage, and I could no longer hold back the tears. The theater went dead quiet. “Maybe I’m using the wrong words,” I said, and then my voice broke for a moment. “But I don’t know the right ones. Maybe the lawyers wouldn’t want me to say anything at all. But you’ve been wonderful. I want to thank you all for saving me embarrassment by not asking questions I couldn’t answer.”

Everyone in the place stood and clapped, and my tears weren’t the only ones flowing. But when the applause stopped, the questions started.

Lawyers? Did he say lawyers

? And the word started to rocket across America:

Martin and Lewis are having a feud

.

It’s hard to explain to a 999-channel, Internet-connected, all-entertainment-all-the-time world what it felt like to be a big act in a much simpler time, having very public trouble. Then imagine the commercial implications of a rift between Dean and me. We had commitments out there worth literally tens of millions of dollars. We owed Hal Wallis five more movies, for starters. We had TV and radio contracts, theater bookings, and commercial endorsements. And we had some very big shots—most notably, Wallis and our mega-agent at MCA, Lew Wasserman—very, very concerned.

Still, I’d come to the point where I couldn’t take it anymore. The day after I got back to L.A., I marched into Lew’s office and said, “Please do something, anything, because I can’t continue working this way.”

“What about Dean?” Lew asked. He was, after all, agent to both of us.