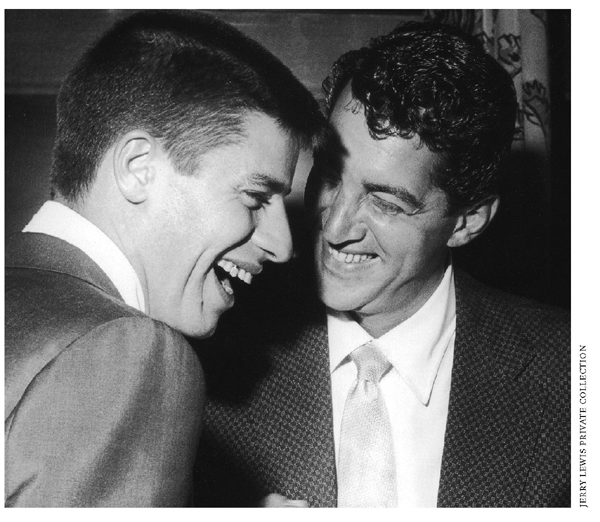

Dean and Me: A Love Story (12 page)

Read Dean and Me: A Love Story Online

Authors: Jerry Lewis,James Kaplan

Tags: #Fiction, #Non-Fiction, #Music, #Humour, #Biography

This was Willie Moretti.

Dean and I had gotten to know Willie and his closest New Jersey associate, Longy Zwillman, at the Riviera nightclub. Like many of the major nightclubs of the day, the Riviera had a private gambling club on the premises: The Riviera’s was called the Marine Room, and whatever Willie and Longy’s business arrangement was with Ben Marden, Willie and Longy paid very close attention to the Marine Room’s operations— as they did to the operations of the Riviera as a whole. And because my partner and I were very big business for the Riviera, Willie and Longy extended us every courtesy, including, most especially, their friendship.

Dean was of two minds about wiseguys. On the one hand, unlike Frank, he never went out of his way to cultivate them. Believe me, Dean could have found any number of such gentlemen who would have been tickled pink to help him with his career early on. But he elected not to, because it was never his way to cozy up to anyone.

On the other hand, my partner always felt that you treated people the way they treated you—no matter what anybody else said about who those people were or what they did. And as I’ve said, the major Mob figures were, each and every one, all gentlemen to us, so we gave as good as we got.

Longy Zwillman, the longtime boss of New Jersey, was a real gent— quiet, well-dressed, and with beautiful manners. Willie Moretti was a little rougher around the edges, a little louder and funnier. When he appeared on the nationally televised Kefauver hearings on organized crime, he told the esteemed members of the congressional committee next to nothing—but in a very entertaining fashion. He charmed the pants off those congressmen, and when one of them thanked Willie at the end of his testimony, Willie invited the whole bunch of them to come visit him at his house on the Jersey shore!

Somewhere backstage.

That was Willie Moretti.

He was widely liked in the world of organized crime, but he also had made a powerful enemy of New York boss Vito Genovese, a dark character who didn’t have many friends anywhere. Still, we liked Willie, and when he invited Dean and me to his daughter’s wedding, we were genuinely touched. Our present to the bride and groom (and the bride’s father) was a command performance.

Dean and I were scheduled to appear between our first two shows at the Copa, so Willie knew we had to get on and get out. We arrived as the families were gathering to make their presentations of gifts to the newly married couple. And gift-wise, we’re talking very big bucks.

The young couple sat at one of the larger tables in the room, behind a stack of white envelopes, and the line of people with more envelopes extended all the way out into the foyer.

Dean and I made our way to the ballroom. Willie saw us, and had the envelope line shifted into the ballroom so the people would be able to see us. He tapped a water glass and announced, “We have Martin and Lewis with us for some entertainment.” He wasn’t quite Ed McMahon, but we went on, did a few bits, and took our bows to somewhat distracted applause. Willie thanked us, but I knew we hadn’t done as well as we could have because—let’s face it—we were upstaged by all that money.

But Willie always remembered a favor, and always showed up at our shows at the Copa. And one night three years later, he came backstage, all smiles, and invited us to join him for lunch that coming Thursday at his favorite restaurant, Joe’s Elbow Room in Cliffside Park, New Jersey. Sure, we said.

As we walked into our hotel suite very early on Wednesday morning, I suddenly remembered Willie’s invitation. We always finished our last Copa show at four-thirty A.M., and I was never able to calm down and fall into bed until around six. As nice a gentleman as Willie Moretti was (to us, anyhow), it made me weary just to think about hauling my behind out to Jersey the next day for lunch. I said, “Do you think we really need to have lunch with Willie?”

“Sure we do,” Dean said. “One, you don’t offend someone once an invite is made and you’ve accepted. Two, you don’t offend Willie Moretti.” He gave me a look. I got it.

But when I woke up that afternoon, I was dragging. I barely made it through our three shows that night, which is not good if the people are paying to see you bounce off the walls. Sure enough, when I woke up the following morning, I was as sick as a dog, my neck swollen to the dimensions of a medium-size life preserver.

I had the mumps.

The

mumps

, for Christ’s sake—that’s what children get. “I’m twentyfuckin’-five!” I screamed at the doctor who’d just examined me.

Stay in

bed

?!

“We do three shows tonight!” I told him.

“Not tonight,” the doctor said. “Not this night, and not any night for the next ten days, at least. If you don’t respect this illness, it can get away from you and you’ll do twenty-one days in bed. You’d better listen to the doctor!”

After he left, I called Dean. “You’ve got

what

?” he yelled.

“Are you coming over?”

“Aren’t you contagious?”

“No, I’m Jewish!”

Dean laughed, came over. We sat and watched daytime television. In 1951, it was mostly test patterns and cooking shows with Jack Lescoulie. We had a very dull day sitting there, with me depressed and Dean on the phone to Jack Entratter at the Copa, trying to figure out what to do about the next week and a half.

Before long, Dean and Jack got Frank Sinatra to pitch in and work with Dean for a couple of days. Then Joey Bishop agreed to help out. As long as there was another name with Dean, it seemed to soften the blow of Martin without Lewis. But in those days, believe me, neither one of us was prepared to set the world on fire as a single.

After a long afternoon of daytime TV and penny-a-point gin rummy with my partner, I looked at the clock for some reason. Four-twenty-five. All at once, I remembered—our lunch with Willie! Jesus! Dean phoned New Jersey, prepared to give our very legitimate excuse . . . but no one could be reached at Willie’s office. This was long before answering machines: There was no way to leave a record of our good intentions. We had officially stood up one of the most powerful wiseguys in the metropolitan area.

The mood in my hotel room got even glummer as we channel-surfed (1951 channel-surfing in New York City: six channels) and stared at the boob tube. Having had our fill of soap operas, we switched to the fiveo’clock news—and suddenly a Special Report filled the Philco’s twelve-inch screen. There was a flash shot of a man lying in a pool of blood on a white-tile floor, while a deep voice intoned, “This is mob boss Willie Moretti, killed today in a gangland-style hit while he ate lunch in a restaurant in Cliffside Park, New Jersey....”

I looked at Dean. Dean looked at me. Neither of us said a word.

“The Money Song” did all right for us, but since it didn’t look as though we were going to blaze any trails as a novelty act in the music business, Capitol decided to record Dean alone. Interestingly enough, his first solo disk (this was still in the days of the 78-rpm record, just before the LP format came in) was Frank Loesser’s “Once in Love with Amy,” from

Where’s Charley?

—the Broadway hit we’d seen with June Allyson and Gloria De Haven.

From 1948 to 1950, Dean made quite a few records for Capitol, songs like “Powder Your Face with Sunshine (Smile! Smile! Smile!)” and “Dreamy Old New England Moon”—songs that did not exactly establish him as a solo singer. But then he had a minor hit with a number called “I’ll Always Love You,” from

My Friend Irma Goes West

, followed by another song called “If,” which Perry Como had recorded earlier and taken to number one.

At the time, it was perfectly fine with Dean to ride Perry Como’s coattails: He still felt as lucky as I did to be soaring along on our fabulous comet. It was always a big part of his charm that he refused to take himself seriously as a singer. But the day was swiftly coming when he would have to rethink that position a little bit.

CHAPTER NINE

YEAR BY YEAR WE KEPT MAKING MOVIES, CRANKING OUT TWO or even three (!) pictures every year. In 1952, we did

Sailor Beware

and

Jumping Jacks.

In 1953 came

The Stooge

,

Scared Sti f

, and

The Caddy

.

We stuck with the blueprint that I’d finally been able to talk Hal Wallis into on

My Friend Irma

, the formula that was the basis of our act: the Playboy and the Putz. But just as we stuck with that formula, we also

got

stuck with it. We settled into a rut. And if you want to know what kept us from blossoming and finding our highest comic potential onscreen, I can tell you the answer in two words: Hal Wallis.

Ed Simmons, a comedy writer who, along with another young whippersnapper named Norman Lear, wrote

The Colgate Comedy Hour

with Dean and me, once told an interviewer a story about getting hired by Wallis to rewrite

Scared Sti f

. “We had always liked Dean,” Simmons said, “ ’cause Dean was very funny, and we felt he wasn’t given a chance to do things in pictures. . . . So we kept putting in scenes for Dean, and Hal Wallis kept sending them back. . . . Finally, he called us up to the office and said, ‘Why do you keep sending me this stuff?’ And we said, ‘Because Dean is funny. And he should be doing this stuff, this is a good scene for him.’ And he said, ‘Fellows, look. A Martin and Lewis picture costs a half-million, and it’s guaranteed to make three million with a simple formula: Jerry’s an idiot, Dean is a straight leading man who sings a couple of songs and gets the girl. That’s it, don’t fuck with it.’”

That was Hal Wallis.

As I’ve said, our producer had had a long and distinguished career in movies—beginning (I kid you not) in 1927 as the publicist for

The Jazz

Singer

, the very first talking picture. He’d made all those great dramas—

Casablanca

,

Sergeant York, I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang—

as production chief at Warner’s, and, once he’d set up shop as an independent producer at Paramount, had discovered and signed Kirk Douglas, Burt Lancaster, Anna Magnani, and Charlton Heston.

And then Martin and Lewis.

But the thing about Hal Wallis was that while he was great with drama, when it came to comedy, he had a sense of humor like a yeast infection. And I told him so. He said, “Listen, kid, I’ve been making films for forty years.”

I said, “You could’ve been making them wrong!”

He wasn’t crazy about any artist who challenged his concept of a movie, and I challenged him big-time. I never let Wallis alone. I was in his office six times a day questioning the script. Needless to say, he wasn’t charmed. His attitude was: Just get Dean and Jerry in front of the cameras and shoot enough footage to make a feature-length movie. “All the Martin and Lewis movies make money,” he was fond of saying. “So what’s the difference how it turns out?”

Clearly, this wasn’t headed in a good direction, especially where Dean was concerned. But Dean played more or less the same game with Wallis that Wallis played with us: He never let the producer know how perceptive he was. I think Wallis thought Dean was a fool... playing golf all the time. That’s where he made a big mistake.

You see, I was in charge of everything where the act was concerned; Dean played golf. That was our arrangement. That was the way Dean wanted it. He loved golf, pure and simple. He loved that game more than he loved women—and he was very fond of women—and much more than he liked alcohol.

Meanwhile, I was falling in love with every aspect of the movie business. And so I had more and more to do with production. Still, while part of Dean wanted things that way, there was another part of him— aided and abetted by all those people who gathered around him as he grew more successful, the people I called

shit-stirrers

—that began to feel like a second fiddle.

The question might have occurred to you by now: Did

I

go to Wallis and demand more for Dean to do in our pictures? Sometimes I did. What was always front and center in my brain was the team, and the Act: Were Dean and Jerry coming across on the big screen in some close approximation of the way they came across on stage? If Dean was diminished in that equation, we both were diminished.

But—was my ego growing? Was I enthralled, enamored, enraptured by all that I was learning about film? Was I knocked out by the unlimited comic possibilities for the Jerry character onscreen?

Yes, yes, and yes. It all happened silently, the way one week you can see perfectly and the next week you need glasses: I was developing a certain myopia about Dean. And since my partner feared and hated any sort of showdown, he wasn’t calling me on it. Yet.

But others were beginning to tell him about it. All his life, Dean was a pretty solitary cat. He never went in for cliques or crowds. But his magnetism was so strong that there were always people around who wanted to get close to him, be on his good side. He was

Dean Martin

, for God’s sake! Guys in bars, casinos, golf-course clubhouses—he spent a lot of time in those places—would sidle up to him, tell him how great he was. All by himself.

At the same time, I think Dean was starting to feel that he was ready to stretch as an actor. But in the meantime, he was seeing all those reviews that put him down or just ignored him. He had to listen to

Jerry,

Jerry, Jerry

, all the time.

And the shit-stirrers kept stirring....

We didn’t disagree about much for the first half of our decade together, with one exception: his singing. I loved it and thought he could do more with it; he would never take it seriously. Once I asked him, point-blank: “Just once, would you sing a song straight?”

He gave me a funny look. “I do,” he said.

“No you don’t,” I told him.

When I pressed the issue, things got pretty sticky between us. I’d been thinking, Hey, maybe he could have a fourth song; it would be great for him. We were on for two hours. What’s the big deal? Another three minutes? It was okay with me.

So I said, “You know something? You’re doing so good in your spot, maybe I’m coming on too early.” He said, “Fuck you! Whattaya talkin’ about? You’re gonna spoil what we got. Forget it.”

His mind was made up, but when we played the Fox Theater in San Francisco in 1951, the reviewer in the

Chronicle

wrote a big rave about the show—without mentioning Dean once. That hurt. I saw it in his eyes. And—for both our sakes—I found myself giving him a pep talk.

“You know something?” I said. “They’re always going to like the kid who makes the biggest noise. They’re always going to pay attention to the fuckin’ monkey. You’re going to hear more about him than the straight man. Nobody ever talked about George Burns. It was always Gracie. When Jack Benny and Mary Livingston worked in vaudeville, they didn’t know who Jack Benny was.”

I said, “You have to know that the straight man is never given the kudos that the comic gets. And I just need to know you’re okay with that.”

This was really opening a sore. Dean said, “Jerry, look. Your father told you once, Be a hit. With the monkey act, with a couple of broads, with two balls and a watermelon. Whatever—just be a hit. We’re a big hit. And you need to know that

I

know when our film is on that screen and I start to sing, the kids go for the popcorn.”

“I don’t think that’s true,” I argued. “I don’t think little kids go for popcorn at any particular time.”

But in my heart, I knew he was right. Kids go to the movies to laugh and see action, and singing and love scenes slow things down.

What I

should

have said was that the people also went for popcorn during Crosby’s songs. And Perry Como’s. And every other singer who went into film, including Frank. The songs and the kissing scenes—that was the time for popcorn.

But Bing Crosby was Dean’s first idol, and he often felt he was walking in Crosby’s shadow. There were too many kids in Steubenville—and too many reviewers later on—who said, “You’re imitating Crosby.” Dean carried that around with him. I’d tell him, “Crosby has a voice, but he’s got no fuckin’ heart, you putz. You got heart.”

He also had a thing about Frank. Dean always felt like the guy who had subbed for Sinatra at the Riobamba. Sinatra was so great, why even try to take him on? Even though what Dean did and what Frank did was apples and oranges.

Every once in a while, Dean would make some joke about how he’d had to sing on the radio for free. During the war and just after, several of the stations in the New York area had what they called “sustaining”— nonsponsored—programs. When there was no sponsor, there was no pay for the talent: It was strictly a showcase.

“It may interest you to know,” I said, “that Sinatra was on Hoboken radio sustaining.”

“Horseshit,” Dean said.

I said, “Really?” I went to the phone and called Frank. He confirmed that he’d sung on Hoboken radio for free. He said it was only for three days, but he had! I said, “Paul, they couldn’t afford to pay you. We were coming out of a depression and a war. They were broke.”

After he had a couple of small hits on Capitol in the early fifties, I decided to take matters into my own hands. Was I being overcontrolling? Maybe. But I needed to protect our act. In 1952, we were in preproduction on our new picture,

The Caddy

, and we needed some songs for Dean. So I went to the great Harry Warren, the Oscar-winning writer of such songs as “Forty-Second Street,” “You Must Have Been a Beautiful Baby,” and “Chattanooga Choo-Choo,” and his lyricist Jack Brooks, and paid them $30,000 out of my own pocket. I didn’t want Dean to know I hired them, and I never told him. But I knew that Harry Warren could write hits, and I said to Harry, “I want a hit for Dean.”

And he wrote one. Boy, did he write one.

Cut to the following fall, about a month after the release of

The Caddy

. Dean phoned me from his dressing room on the Paramount lot: “What are you doing?” he said.

“Darning a sock,” I told him. I waited for the laugh, then remembered I had used the line before. “Why, what’s up?”

“Wanna take a ride?” he asked.

Six-year-old voice: “Ooh, goody, I love rides.” Grown-up voice: “Where we going?”

“It’s a surprise. See you outside.”

We always kept our cars parked right behind the dressing-room area, poised for action. When I opened the door, Dean was sitting at the wheel of his blue Cadillac convertible with the top down, a grin on his deeply tanned face. I think he loved that car more than any he ever had, and he had a few.

I got in and he started her up. We pulled through the studio gates, drove down Melrose, took a right up Vine, and turned left onto Sunset. Quite a few heads turned as we passed by. It was a warm, hazy, Indian-summer day in L.A., and we were at the height of our fame, riding down Sunset Boulevard in an open Cadillac! An open

blue

Cadillac. I was very aware of the impression we made, and I loved every second.

And so did Dean. As I glanced over at my partner, I could feel his total satisfaction. He was at peace with the world: smoking his Camel, driving his great car, his partner at his side. He never said it, but his eyes reflected a happy man.

As we pulled up in front of Music City, Dean stopped the car and pointed to the huge store window, where a double-life-size photo of himself stood, next to a sign announcing his new single, “That’s Amore.”

“Hey,” he said. “Is that one handsome Italian, or what?”

Neither of us had any idea that day what a monster hit “That’s Amore” would become (it would sell two million platters as a single, and be nominated for an Academy Award) and what kind of effect the song would have on both our lives. It was a number Dean tired of singing after a couple of years, but for the time being, it gave him an identity with the public that he had never had before.

In

The Caddy

, Dean played an up-and-coming golfer who leaves the game to become a professional comedian. In real life, I don’t think he’d have minded doing it the other way around.

As a struggling young singer in the forties, Dean couldn’t afford to

She wouldn’t leave me alone.

With his natural grace and athletic ability, he overcame his late

start and got better and better, finally whittling his handicap down to a six.

Not bad for a kid from Steubenville, where all the hitting you did was at each

other! Once we moved out to the Coast in 1949, he figured hed found golfing

heaven. The second house he and Jeannie bought was right next to the Los Angeles

Country Club.

Dean loved golf because it was made for his chemistry: quiet, soft breezes, green grass, no people gawking at him, and a bar at the nineteenth hole. But mainly quiet. The few words you might exchange with your partners as you strolled down the fairway were plenty for him. And he chose his partners carefully. Or so he thought.

When Dean joined the California Country Club, his golfing skills made him the envy of much of the membership. But those same skills also made him a target. The advice his parents had given him about keeping to himself had insulated him from potential friends and annoyances alike. Still, there were times that even he let his guard down. In short order, he fell in with a group of hustlers headed by a character named Bagsy Kerrigan. These were guys who claimed to have a certain handicap, nine or twelve or sixteen, but who in reality could play lights-out, par or subpar golf whenever they wanted.