Dean and Me: A Love Story (14 page)

Read Dean and Me: A Love Story Online

Authors: Jerry Lewis,James Kaplan

Tags: #Fiction, #Non-Fiction, #Music, #Humour, #Biography

Meaning what? That I crowded Dean? Smothered him with attention and affection? I suppose I did sometimes. Did I suck all the air out of the room? Sure, sometimes. I never claimed to be a shrinking violet.

Did Dean ever do anything for me?

The answer to that is a most definite yes. He might not have been a gift-giver, but for ten years he gave me the huge gift of his presence. And there were other important perks, as well.

For one thing, he protected me.

After all, that’s what a big brother does, right? Maybe part of our problem, as I got older and stronger and surer of myself, was that I needed his protection less. But early on I needed it plenty.

The first time we played the Flamingo, in Vegas, was in 1947, just six months or so into our act. Bugsy Siegel, who’d taken on the ownership of the Flamingo from its original founder, Billy Wilkerson, and made the casino his personal obsession, was still alive (but not for long: He would be rubbed out that June). I had the chance to meet the handsome gangster himself when I got myself into a little bit of a jam—$158,000 worth—as a newcomer to the craps and blackjack tables. As I said, I talked my way out of that problem, but there was another problem at the Flamingo that I talked my way into.

There was a convention of Tall Cedars of Lebanon members staying at the hotel, and they were all easily identifiable by their unique headgear: A green, pyramid-shaped fez with a long tassel, it looked like nothing so much as a dunce cap.

One night at our dinner show, I spotted that hat on one of the guests. Being as nuts as I was at that age (twenty years and change), I saw him as the defining moment of our act. “If ever a man needed a hat job,” I said. “Come on. Don’t feel bad, I’ll get you a number for Stetson.”

Everyone laughed but him.

We finished our show, changed our clothes, and went out front to hear that we’d done a good job. We strolled over to the bar and sat down. Dean ordered for both of us: very dry martinis. He loved olives, and I loved onions. As I ate them, he’d say, “It’s a good thing they’re pickled, or you’d be alone on stage later.”

As we sipped our drinks, I felt the presence of someone standing very close to my back. Then a hand grabbed my jacket and slowly turned me around. (I was lucky that the stool swiveled.) There he was, old Dunce-head himself. “If I don’t get an apology, I might knock you into next week.”

Dean rose and, without saying a word, took the man’s hand off my jacket, put one big hand between the man’s legs and the other hand around his neck, picked him up as though he weighed nothing (he was at least 190 pounds), and hurled him into a shelf of glasses behind the bar.

The noise of shattering glass shook up the casino and management. One of the Flamingo’s owners, Gus Greenbaum, strolled over to us and saw the Tall Cedars of Lebanon man plucking pieces of glass from the seat of his pants. (Gus was a Mob torpedo out of Chicago, but he was always a lovely man to me, and we would remain friends until his untimely demise in the late fifties, when he and his wife were both hit for an infraction I never understood.) Gus was calm, but serious. “Look,” he told us. “You guys need to go to your suite and let me deal with this.”

And deal with it he did. A little while later, the phone in our dressing room rang. It was Gus Greenbaum. “Tell Dean that his punching bag got an urgent call and had to leave town tonight,” he said. I started to thank him, but he interrupted me: “Case closed!”

A little while later, Dean gently reminded me: “Look, Jer, before you shpritz someone ringside, just keep in mind who gets those ringside tables!”

“How am I supposed to know if it’s a wiseguy?” I asked him.

“Oh, you’ll develop a sixth sense about these things,” he assured me.

And I did. Dean’s advice was sound, and I mostly remembered it.

There were times Dean protected me from others, but there were more times he had to protect me from myself. In 1952, Purdue University decided it wanted us to entertain at its homecoming festivities. Now, Purdue happened to be somewhere in northern Indiana, but since we happened to have just finished an engagement at the Copa and were on our way home to L.A., we agreed.

But—West Lafayette, Indiana? Deep in the cornfields of the Hoosier State? We asked for a very large sum of money (I mean

very

large) for the one evening, thinking we could get out of it that way. But Purdue promptly agreed. We were stuck, but good.

The whole crowd of us—Dean and I, Dick Stabile and our entire twenty-six-man band, our security guys, and our press agent Jack Keller—all flew to Chicago, then got on a bus and into a couple of limos for the three-hour drive south to West Lafayette.

One thing the planners hadn’t counted on, though, was that the light snow that was falling as our convoy pulled out of O’Hare Airport would turn into a full-fledged blizzard. It looked like a grip on a sound stage had been cued to let the white stuff come full force!

The longer we drove, the darker it got and the more heavily it snowed. This was before the Interstate Highway System; we were slogging along on two-lane blacktop, making very slow headway into deepest Indiana. After five hours, it became apparent that we weren’t going to reach the nice hotel in West Lafayette anytime soon.

Dean and I were in the head limo, along with Dick, Keller, our pianist, Louie, and our drummer, Ray Toland. The six of us started peering into the darkness for someplace to stay—six guys in a limo in the dark ain’t the tunnel of love, folks! Tempers were beginning to rise when Dick, who was in the front seat alongside the driver and Louie, lit a cigarette. Which wasn’t unusual in itself (we all smoked)—but after the match blew out, the four of us in the back (two in jump seats) began to smell an odd aroma.

Dean smiled. I wasn’t sure what was going on until I heard Ray tell Dick, “Gimme a hit!” Now I knew....Dick passed the reefer back, and Ray sucked in the smoke like it was his last day on earth. Then he passed it to Keller, who inhaled, and passed it to Dean—who puffed on it like a pro, then passed it back up to Dick.

“Hey!” I called. “What is this shit? I’m twenty-five, going on twenty-six years old, for Christ’s sake! Give me that thing!”

“Okay, kid, go slow,” Dick said, handing me the joint.

I inhaled deeply, as I would with one of my cigarettes—and Dean yelled, “Let the coughing begin!” And did it begin. I must’ve coughed for five solid minutes.

Then I asked to do it again.

“Here’s a new one, guys,” Dick said, and Dean handed it to me. We went around again, and pretty soon I was feeling exactly like Errol Flynn. How easy it would be, I thought, to step outside and leap over the limo....

After a while, none of us cared about the gig, the storm, or the hotel. We just kept riding into the night, as the windshield wipers slapped at the heavy flakes. Soon a chorus of snores echoed from the back seat. Dick was still awake up front, and I asked, “What was that I smoked?”

“It’s called Emerald Feet,” Dick told me. “Comes from an island in the Indian Ocean. Very expensive—about a buck-fifty a joint.”

“Can we get more?” I asked.

Around two in the morning—eleven hours after landing at O’Hare— we rolled into West Lafayette. The night clerk at the hotel gaped at the sight of Martin and Lewis and a dozen other guys stomping in out of the snow-storm.

“I saw you guys on Ed Sullivan!” the clerk told Dean and me. “You were great!”

As we thanked him, Keller made a remark too obscene to repeat— believe me—about Sullivan and a nice lady singer of the 1930s named Ruth Etting. We all screamed like chimps at a banana festival, and the night clerk stared some more.

But I was the one who couldn’t stop laughing. Dean explained to me, in between my giggles, that a new pot smoker is very vulnerable and can stay high for days. I remember now that he had a worried look as he said it—he was thinking about our show—but at the time, I couldn’t have cared less about any of it. As Dean and the security guys helped me up to our suite, I was singing my head off through the halls of the sleeping hotel. The guys tried desperately to quiet me, but to no avail. I was still singing as they bundled me into bed.

Finally, the house detective came up to ask what was going on. I jumped out of bed and proceeded to tell him all about smoking pot, informing him that I would be all better in a couple of days. Eventually, Dean got me settled again.

The next morning, he came into my room to see if I was all right. Oddly enough, I felt perfectly fine, but I still had the sillies—I couldn’t stop laughing.

Dick walked in. “For God’s sake,” Dean said. “Is there anything we can give him to settle him down?”

“Hair of the dog,” Dick said.

“What?” Dean said.

Dick assured him that he had done it before—that it balanced the high. He took a joint out of his pocket, lit it, and handed it to me. “Okay, Jer,” he said. “Nice and easy. Just one or two small puffs, and you’ll feel like a new man.”

Well, I took the puffs, and I was anything but a new man. In fact, I was right back to being Errol Flynn. I couldn’t wait (I told Dean and Dick) to get to the rehearsal and let the band know I had tried pot!

Dean looked aghast. “You can’t say that to anyone,” he told me. “It’s against the law.” His expression turned to concern. “Jer, are you going to be all right? I don’t want to let you go on stage and humiliate yourself.”

I bit my lip. “I’ll be okay,” I assured him.

He watched me like a hawk during the rehearsal. Now I had totally lost my bubble—I was dopey and tired, not even sure I could do the show. And we were five hours from curtain.

“Take a walk with me, Jer,” Dean said.

Dean never walked if he could help it (before golf carts, he played gin), so I knew this was serious. We headed out across the campus. The bright sun reflecting off the snow was killing my bloodshot eyes, but the fresh, cold air began to revive me a little. As we walked, Dean explained what pot does to the body, and some of the differences between reefer and alcohol. Even high, I couldn’t help but marvel at his big-brotherly wisdom, and at my good luck in being the recipient of it.

Then he looked me right in the eye. “Look, Jer,” he said. “If you don’t feel like you can make it tonight, I’ll cancel the whole gig.”

“Not on your life!” I said. The auditorium’s 3,000 seats had sold out, and now that we were just across from the theater, I could see hundreds of people waiting for standing-room tickets. “I’ll be fine, Paul,” I told him.

Dean walked me around for quite a while, through the local park and then finally backstage to our dressing rooms. The orchestra played “Blue Nocturne,” then Dick introduced me. As I came out, the crew, the staff, the electricians, the soundmen, prop men, curtain pullers, dressers, and makeup people watched anxiously. They all knew about my pot party of the evening before.

I did the normal welcoming remarks, then went into a pretty funny gag about Dean and me being in college again. . . . Again? Not hardly! I segued into a bit about “I will never go into politics because I do comedy already!” The audience laughed long and hard, while I went on to blast the U.S. government for taxing us so heavily, saying that if they weren’t careful, everybody would wind up on food stamps and they’d wind up having to support us anyway.

This somehow transitioned into a rant about sex and youth versus sex and the elderly. I was aware the audience had quieted down, aside from some nervous coughing. I felt a little like I was working to an audience of Arabs and they knew what I was.

And then, thank God, my partner stuck his head out from stage right and yelled, “If you don’t hurry, I’ll be too old to sing!” The relieved audience ate it up, and it certainly cued me. I introduced Dean, who came and did his three songs to huge applause.

We actually did one of our better shows that night, but we went slow, Dean establishing the tempo so I wouldn’t run on—especially at the mouth!

When we got back to the hotel, Dean ordered me to take a nap, and I almost instantly fell into a sound sleep—and (of course) dreamed I was awake.

From then on, I swore to myself, I would stick to an occasional cocktail.

CHAPTER ELEVEN

DEAN’S THIRTY-SIXTH BIRTHDAY WAS A VERY DIFFERENT AFFAIR from his thirty-fifth. On June 7, 1953, we were in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, aboard the beautiful new Cunard liner

Queen Elizabeth

, heading for our first-ever overseas engagement, at the London Palladium. Hal Wallis, a charter member of the Dress-British-Think-Yiddish sect of Judaism, adored all things English, and since there was no

Colgate

Comedy Hour

in Great Britain to goose our movie-ticket sales, Wallis figured we’d better get over there and show them the merchandise in person. After extended three-way talks between Wallis, his pal Val Parnell, the manager of the Palladium, and our new agents at MCA, we were booked at the great theater for a week at seven thousand pounds sterling.

I’d had to do a little bit of explaining to Dean about the gig—first about that seven-thousand figure, which made him howl until I told him that a pound (at that time) was worth five bucks.

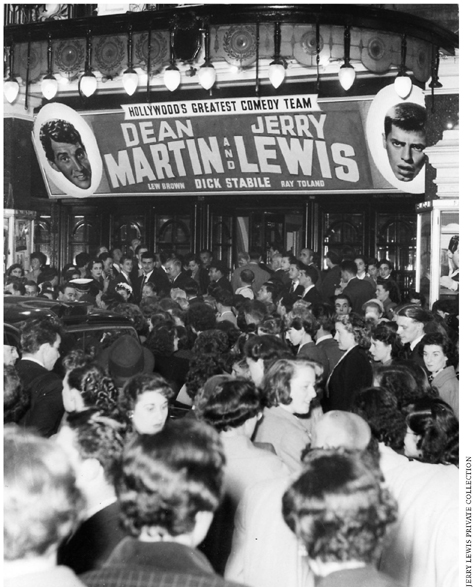

London Palladium, 1953.

Then he asked me about the Palladium. “Is it any good?”

“Good?” I said. “My dad says there are only four theaters in the world that you’ll play if you really make it in show business—the Paramount and the Palace in New York, the Olympia in Paris, and the London Palladium.”

He shrugged, always Mr. Cool. “Okay.”

So there we were aboard the great liner, a party of twenty-four—we took up three full tables in the first-class dining room! Patti and our two sons, Gary and Ronnie, joined us, along with the musicians, writers, dressers, and the rest of the group. The one person who did not make the trip was Jeannie: She and Dean had been having a little trouble lately, and though they’d kissed and made up, she decided to stay back in L.A. and take care of the kids.

Leaving her husband free to have the kind of fun he was so fond of having.

To begin with, the

Queen Elizabeth

had an elegant gambling salon, which Dean said he and I should enjoy. Major mistake! In less than three days playing gin rummy, I owed my partner $684,700. As always, he was most happy to assist me by letting me postdate the check, which I did. I made it out on June 5, 1953, but dated it August 5, 1956 (all in fun, little realizing what any date after July 24, 1956, would mean to us). For the next three years, Dean held on to that check, hoping to do something ridiculous with it one day. He never did. (He may have kept it longer, but I once asked Jeannie if she’d ever seen it, and she said no.)

The night of Dean’s birthday, we had dinner with the ship’s captain. That made me nervous. A captain away from the bridge for two hours, wining and dining and chatting with everyone that came over to say hello to him.... Who was watching out for icebergs?

We were seated apart from the rest of our entourage, and in those days, when my wife wasn’t there, the Idiot was! Dean was squeezed between two old biddies, Mae and Clara. I remember their names to this day because—I later learned from the ship’s social director—they owned a chain of department stores in Texas, making them two of the richest women in that very rich state. They were also (the social director said) on the lookout for husbands! We bird-watched those two for the whole trip. They had some pretty good moves, but no takers.

Also at our table were Anastas Mikoyan, trade minister of the Soviet Union (and later its premier), and Mrs. Mikoyan. Oh, they were a barrel of laughs... not!

The dinner started with a ceremonial hand-washing—hot towels passed all around. “I just left my room—how dirty could I get?” Dean said. I kicked him under the table. Then the caviar was served—real Iranian caviar, about $11,000 a spoonful, and with it a nice small glass of vodka, which the Russian pushed away, motioning for the waiter to get him a tumbler, which he did. We watched in disbelief as Mikoyan held up the water glass, toasted everybody at the table, and gulped it down like Coca-Cola.

Dean took a sip and made a face. “That boy’s got a cast-iron stomach,” he said. “This stuff is lighter fluid.”

I shushed him. “Let’s be polite,” I said. “Just not

too

polite.”

Suddenly, my partner was wearing a very familiar grin and staring over my shoulder. I didn’t have to be told what was going on; I just needed to know where she was. The answer was two tables away, sitting with a bunch of very theatrical types: an absolutely glorious, dark-haired young lady, twenty-one years old at the very most. She and Dean had locked eyes, and she was smiling in a way that told me I’d be seeing very little of him for the next few nights.

I won’t say the girl’s name here, but she was a celebrated young actress whose future seemed full of promise—yet would, in fact, be filled with heartbreak. At that moment, though, she was like the most beautiful blossom in a meadow, ripe for the plucking. She was also in the midst of a very public love affair with another one of Hal Wallis’s actors, Kirk Douglas. Who was not aboard the

Queen Elizabeth

.

Dean’s smile, and the young lady’s, grew broader.

The next morning, the entire cruise staff were out rounding up pigeons for shuffleboard, horse-racing games, swimming contests, and, of course, the perennial amateur shows. At breakfast (Dean was still grinning), the two of us decided to enter the show in disguise. We had our bag of tricks with us—makeup, hats, wigs, beards, musical instruments ... Christ, we could go on stage as anyone at all!

Dean decided to do his Bing Crosby impression (which he did quite well), in wig, golf hat, and mustache, and I would do my Barry Fitzgerald imitation (remember the little Irish actor who always played a priest? Well, believe it or not, I did a mean Barry Fitzgerald), in wig, mustache, and turnaround collar.

We auditioned in the

Queen Elizabeth

’s mammoth showroom and were accepted for the show that night. Just what we were going to

do

in the show was another question—it wasn’t as if we had a screenplay of

Going My Way

lying around!

Day turned into evening gradually and gorgeously, as it does at that latitude on the Atlantic: a soft twilight that seems to last forever. And then it was showtime.

At first, back in costume, we were laughing, but as the master of ceremonies got things going, it suddenly hit us again: What the hell were we going to do?

Then I had an idea. We watched the other acts. The juggler needed a day job. The trainer for the dog act forgot the doggie treats. The dog did nothing, except backstage he left us a gift.

Now it was the singer’s turn. She was a beautiful blonde with flowing locks and extra lipstick on her teeth. She sounded like Tallulah Bankhead in heat. Thank God this was almost over. We were scheduled to follow the mind reader, who couldn’t find his blindfold. A waiter was walking by backstage and I stopped him, gave him a twenty-dollar bill, and took his cummerbund. I slipped through the curtain and handed it to the mind reader, who was most grateful! Until the cummerbund’s metal clips started pinching his temples. He went on, wincing in pain, until his assistant arrived with enough gas to go to Cleveland. I mean, she was whacked out of her mind, so everything the mind reader did, didn’t work. They were on and off in short order, leaving the crowd hysterical. Now it was our turn.

We had the MC introduce us as O’Keefe and Merritt—the billing we’d finally settled on after going through McKesson and Robbins, Harris and Frank, and Liggett and Myers...anything but Martin and Lewis! (I’d wanted to use Dill and Doe, but Dean said no.)

We entered at the same time, Dean from stage right and I from stage left. I was carrying a small wooden box, which I put on the lectern in front of us. Then Dean sang “Too-Ra-Loo-Ra-Loo-Ra” while I did a lot of face-making with the big meerschaum pipe I had clamped between my teeth. Then Dean kept on humming the song as I recited an ad-lib hunk of the speech Barry Fitzgerald gave in

Going My Way

.

CBS was never happier!

When we finished, the audience went ballistic... for English people. Which is to say, more correctly, that they demonstrated a high degree of enthusiasm—most of them being, after all, rather prim and proper and stuffy types who looked like they should have had their pictures on Yardley Soap. The best part was, they didn’t know we were who we were. As they applauded, I opened up the wooden box, removed a small bottle of whiskey and two shot glasses, and poured us each a drink. We toasted each other and drank, then took our bows and exited backstage. Both Dean and I thought we were a shoo-in to take first prize: We knew we had at least twenty-two people out there in our pocket! Then all the acts walked back out onto the stage so the MC could see who got the loudest applause.

He put his hand over the dog act first. Applause was sparse. Next, he indicated the mind reader and his drunken assistant, who got a polite hand. Then it was us. Thunder from our two tables in the back—and polite nods from the rest of the audience. Then the MC put his hand over the head of the singing blonde ... who got a standing ovation! Dean and I slowly walked backstage, pondering our worst failure in quite a while. It might have been sad if it hadn’t been so funny—of course, it took us a few minutes to see the humor.

We should have only known what lay just ahead of us.

For about ten days after landing, we went sightseeing in England and Scotland: Dean loved those great old Scottish golf courses. Then we headed for London. On Monday evening, June 22, we opened at the Palladium. Everybody who was anybody in England was there that night, with the exception of the Queen, who would come a few days later. But Princess Margaret was in attendance, along with many other royals, most of Parliament, and a wagonload of British celebrities, including Laurence Olivier, Vivien Leigh, Morecambe and Wise, Benny Hill, Robert Morley, Alec Guinness (not Sir yet!), Jack Hawkins, Hermione Gingold, along with many friends from Paris ... Maurice Chevalier, Edith Piaf, and Pierre Etaix.

We did a terrific show, one of our best. Dean sang wonderfully and thought I had never been funnier. Dick and the band were great, and we played around with them, tooting along on our trumpet and trombone. We had that crowd in stitches. Then, as we were taking our curtain calls, I stepped to the microphone to thank the audience.

“When we return—” I started.

“Never come again!” someone shouted from the balcony.

That stopped me in my tracks.

“Go home, Martin and Lewis!” someone else shouted.

And then the boos began. It’s one thing to bomb in front of an audience—to hear an awful silence instead of laughs and applause. But boos are something else again. Something ugly and assaultive. All at once, it seemed as though that whole London audience was going nuts: a ton of applause and cheers, along with some very audible booing. Was it Dean and I who were being booed, or were our loyal fans showing their disapproval of the people who’d shouted at us? It was impossible to tell. Dean and I looked at each other, totally baffled, just as the curtain dropped. What was going on?

We went back to our dressing room, which looked like rush hour. There were Larry and Vivien and Alec and Jack and Hermione and Benny and Maurice and Edith, all smiling and drinking champagne. Had Dean and I heard wrong? Had none of the happy celebrities in our dressing room heard the boos? We didn’t ask any questions. We were too busy shaking hands and talking to the press. It was bedlam!

We had to dress for the opening-night party Val Parnell was throwing for us at the posh Savoy Hotel. When we got there, we met with Jack Keller, who hadn’t the faintest idea about the who or why of the booing. He spoke to a few of his English press pals but got no answers. And so the party proceeded, the good feelings gradually washing away the bad.

Then, next morning, came the London papers.

Jack Keller phoned us and said he’d meet us in Dean’s suite. When I walked in, I found them in the living room, where Jack had spread the front pages of all eight London newspapers over the floor, every one blaring a variation of the same huge, black headline: