David Waddington Memoirs (28 page)

Read David Waddington Memoirs Online

Authors: David Waddington

In July I visited London, principally for talks with Mark

Lennox-Boyd

, then the minister in the Foreign Office responsible for Bermuda, but I went to the Lords to see what was going on and in the Lobby was greeted by Lord (Oulton) Wade who cried out in his broad Cheshire accent: ‘Hello, David. Are you brown all over?’ Back in Bermuda my golf was going badly but my excellent aide-de-camp, Eddie Lamb, was beginning to perform for me the function Eb Gaines had performed for John Swan. He was a morale booster, and it was as a result of his efforts that I won my one and only golf trophy. Eddie set up a regimental golf championship. Sixteen agreed to play, four teams of four. Only fourteen players turned up on the day because the second in command of the regiment and Larry Mussenden were recovering from a hangover. My team was second and Eddie had arranged for everyone in the first three teams to get a prize.

In September I was asked to dissolve Parliament for a general election on 5 October. The campaign was not inspiring and when the result was declared, the UBP had survived with a reduced majority, winning twenty-two seats against the PLP’s eighteen, with its lowest ever share of the vote (50% compared with 54% in 1989 and 62% in 1985).

The Opening of Parliament provided the PLP with their first opportunity to expose John Swan as a leader weakened by the election result. The Speaker in the 1989–93 parliament, David Wilkinson, had not stood for re-election. He was a splendidly laid back, some might say idle, figure from an old white Bermudian family and John Swan could not stand him. One reason for this antipathy was that on one

occasion when in the Speaker’s Chair David awoke from a deep sleep and feeling something was required of him announced ‘this House is now adjourned.’ Everyone got up and left except John Swan who was just about to deliver a great oration. John was determined that he would now have a Speaker of his own choosing and he decided on a black Bermudian, Dr David Dyer. On the day before the opening of Parliament I went down to the Senate House for a rehearsal and Dyer was there, also being put through his paces. That night there was the usual eve-of-session party at Government House and from the sniggering of some members of the Opposition I concluded that something was afoot.

The next day I arrived at the Senate House. My first duty was to inspect the guard of honour and I then went up into an anteroom on the first floor to wait for the members of the House of Assembly to answer Black Rod’s summons and begin to process down the hill to the Senate Chamber to hear the speech from the throne. I waited and waited but there was no sign of the procession, and after ten minutes or so I began to worry. Perhaps the PLP had actually hatched some plot to boycott the opening of Parliament. So I sent a messenger up the hill to find out what was going on. And, just as in 1983 Margaret Thatcher’s plan to install a Speaker of her choice had been derailed by Conservative backbenchers who thought the right man for the Chair was the Deputy Speaker – Jack Weatherill – so had John Swan’s plan to install David Dyer. A group of UBP members had sided with the PLP and they and the PLP, a party not known for its sympathy for the Portuguese, had succeeded in getting voted in as Speaker the Portuguese Deputy Speaker – all for the sheer joy of annoying John Swan.

David Dyer of course had been made to look a complete fool and rather unfairly blamed it all on the Premier. It cannot be said that he at once set about engineering John’s downfall but I have little doubt that from that time onwards he wished it most fervently.

*

Nicky was a barrister and a partner in Conyers, Dill & Pearman. He was also the Danish Consul and Chancellor of the Bermuda Diocese.

T

he UBP’s election manifesto ‘A Blue Print For The Future’ had been a detailed policy statement about everything under the sun – from employment to the environment, from drugs to alcohol abuse, from crime to new steps to

eliminate

discrimination. There was no mention of independence and the matter was not discussed at all by the party leaders during the campaign. Furthermore, when John Swan had been asked about the subject by the

Royal Gazette

he had replied: ‘It’s not in the Blue Print’.

In the light of all this there was great surprise when, just before Christmas 1993, John told the press that Britain’s announcement that it was to close HMS

Malabar

, the tiny shore station at the West End manned by just thirteen sailors, was a sign of the unravelling of Bermuda’s ties with Britain. And also when, after Christmas, he blandly announced that independence was back on the agenda, ‘Because of the withdrawal of the Americans, Canadians and British from the Island.’ ‘If I had made independence an issue in the campaign,’ he said with commendable frankness, ‘I would have lost the election.’

The decision to close HMS

Malabar

in April 1995 for a gross saving of £1 million per annum and a net saving which had not even been quantified was really stupid. Any sensible person could have seen the advantages for Britain in at least delaying any decision about

Malabar

until after the American withdrawal from Bermuda which was planned for 1995. As it was, people were able to insinuate

that no possible blame could be attached to the Americans for deciding to leave Bermuda somewhat precipitately because, by resolving to do away with a Royal Naval presence on the Island, Britain seemed to be up to the same tricks.

None of this, however, seemed to be a particularly good reason for John Swan using HMS

Malabar

as an excuse for resurrecting the issue of independence, for the likelihood of the closure of

Malabar

had been known for some time. The truth was that rarely from 1982 onwards had John missed an opportunity to force

independence

onto the political agenda and here, after an election result too close for comfort and with demographic change working against the UBP, he could surely, he thought, persuade his Party that only by raising again the emotive issue of independence would they be able to avoid a UBP debacle five years on. And while commonsense must have been telling him that independence was a divisive issue within the UBP and might well dissolve the glue which held that precarious coalition together, one very influential member of the business community, Donald Lines of the Bank of Bermuda, was telling him that this time the furious opposition from Front Street which had followed the raising of the banner of independence in the past might well not be repeated.

In January 1994 the Premier talked to the press about the

possibility

of having a referendum on independence in the near future. He said this without the authority of Cabinet, and when Cabinet met, one of the members, Ann Cartwright DeCouto, complained, saying that if the Premier wished to raise these issues, things should be done properly and a paper presented to Cabinet for discussion. A paper was swiftly drafted and presented to the next Cabinet meeting, and by a majority the Premier’s plan for the setting up of a Commission of Inquiry to explain the consequences of independence and for a referendum on that issue was approved. Ann DeCouto promptly resigned as a minister.

A Referendum Bill was then published, and in February it was passed by the House of Assembly by a majority of twenty to

eighteen

. At this stage, however, the PLP tabled a motion to halt the setting up of the Commission which, according to the Bill, had to report before a date was set for the referendum, and the Senate then also proceeded to put a spanner in the works.

The Senate was composed of eleven people. Five were appointed by the Governor on the advice of the Premier, three by the Governor on the advice of the Leader of the Opposition and three by the Governor acting in his discretion. So if the ‘Opposition’ senators and the ‘independent’ senators voted together, the government could be defeated; and this time it was defeated, first on a motion that the Referendum Bill should not be discussed in the Senate until the Opposition’s objections to the Commission of Inquiry were resolved; and then when the Senate relented and did agree to discuss the Bill, it proceeded to vote for an amendment which provided that in the referendum a majority of those entitled to vote had to vote ‘yes’ for there to be a mandate for independence.

In the following weeks there were many rumours of plots to get rid of the Premier and one actual plot to install John Stubbs in his place, but Swan survived. The Referendum Bill did not. Having refused to accept the Senate amendment, John eventually announced that a committee of ministers was to be appointed to draft a Green Paper setting out the pros and cons of independence, that the existing Bill would be dropped but that in the next session yet another Bill providing for a referendum would be put before Parliament.

In March 1994 Bermuda had a well-earned rest from all the scheming and feuding over independence. After months of

planning

there was a state visit to the Island by the Queen and Prince Philip – the first since 1975. A committee had sat for months

devising

a programme which would suit everyone, and everyone’s part had been rehearsed. We even had the whole Cabinet on parade on

the Sunday before the arrival, learning where they were to line up and in what order, how a bow should be executed (from the neck not the waist) and how the royal hand should be taken assuming it was offered (not in a vice-like grip). We were prepared.

The Queen had left the royal yacht in the Bahamas and was coming by air, and at 2.25 p.m. precisely on Tuesday 8 March 1994 Gilly and I arrived at the airport. In a moment or two the plane had landed and was taxiing down the runway towards us. Miraculously out of the roof there appeared the Royal Standard and at 2.30 p.m. the doors opened and the Queen came down the steps. I presented Gilly and the Premier at the foot of the steps and after a

twenty-one

gun salute and the inspection of a guard of honour came the presentation of all the other dignitaries.

The plan then was for the Queen to go to St George’s for a

walk-about

in the town square – travelling in the Daimler which was now twelve years old and temperamental. An American had offered us the loan of his Rolls-Royce and to ship the car from the States for the occasion, but the Queen had been adamant that she did not want that sort of fuss. If the Daimler had broken down, we would have been in a fix because the restrictions on car size in Bermuda from which only the Governor was exempt meant that the Daimler was the only big car on the Island: but it had been gone over from top to toe and was looking right royal, and we hoped it would not disgrace us.

After the walk about in St George’s the Queen was supposed to get back in the car to go down the road a little way to the Tucker House, a lovely seventeenth-century National Trust property, but she delighted everyone by ignoring orders and striding off down the street on foot. Gilly and I then left for Government House, to be on parade there when the Queen arrived.

Government House was packed with Easter lilies and looked superb. For months workmen had been about the place carrying out repairs, redecorations, carpet cleaning etc. The Bermuda National

Trust had undertaken the refurbishment of the royal suite where furniture had been touched up, chairs reupholstered and the canopy over the four poster bed cleaned. We had been very lucky with the canopy. During the preparations for the visit a member of the recce party which had come out from London had insisted on Gilly lying on the bed and looking skywards. She did so and saw for the first time that the canopy was in an advanced state of decay. I, in my turn, had made a complete fool of myself over the lavatory. At a dinner party I had enjoyed myself explaining how hideous was the loo in the royal suite and how I had insisted on its replacement, but after dinner when I was invited upstairs for a wash and brush-up I discovered that our hostess was the proud possessor of a loo similar in every respect to the one I had had removed to please the Queen. On returning downstairs I had difficulty looking the lady of the house in the face.

The Queen arrived at Government House at 4.15 p.m. and there was an investiture in the dining room. A short time to change, and then we were off to the Speaker’s banquet at the Southampton Princess. Trumpeters from the Bermuda Regiment had been

assembled

to blow a fanfare as the Queen entered the vast ballroom in which nearly 600 people were waiting to dine. The Speaker, Ernest DeCouto, had been told to pause at the door so that the

trumpeters

could prepare themselves; but Prince Philip who was two paces behind and getting impatient poked him in the back and asked him why we were all hanging around. Ernest lost his nerve and propelled the Queen into the room and straight onto the platform. The trumpeters lost their chance to sound a note and grumpily popping their instruments under their arms, slunk out of sight.

The food was excellent and the evening was voted a huge success even by those who thought it was rather offside for the Premier to make a speech which sounded very much like a bid for

independence

. ‘Our destiny,’ said Sir John, ‘was once determined in part by our position as the Gibraltar of the West. Now we must face taking

responsibility for our future by ourselves. I believe we are equal to the task.’ Some of the Premier’s colleagues denied that what he had said had anything to do with independence; but the

Mid-Ocean News

commented: ‘If it looks like a duck, walks like a duck and quacks like a duck, it is usually safe to assume it is a duck – except in Bermuda, of course, when it is a Swan who has been misrepresented.’

Most people at the banquet missed a far more significant event than the Premier’s speech. As the Queen rose to speak Ernest DeCouto decided that the microphone, which had been placed in front of her at just the right height, needed adjusting and as he leaned across to fiddle with it some of us could see disaster looming. Prince Philip shouted ‘Don’t touch the mike!’ but it was too late. As the Speaker leaned across the front of the Queen his cuff collided with the Queen’s glass of port and its contents descended on to her dress. With great presence of mind she covered the stain with her handbag and proceeded as if

nothing

had happened. The dress, I have little doubt, found its way into the dustbin.

The next morning the Queen and Prince Philip planted a tree each in the Government House garden, which was a blaze of colour with wild freesias in abundance. We then set off for the hospital. On the way up to the front entrance a little gathering of women were carrying placards which read:

‘The corgis of Bermuda welcome Your Majesty’ and there they were, all twenty of them, slavering in welcome – the dogs of course, not the women. On the way back down the drive the Daimler slowed to a halt and one of the women came forward and a few words were exchanged. Talking to Gilly about the incident later in the day the Queen said, ‘That dog was called Lillibet. I was quite surprised. I thought it would be Queenie.’

Then it was on to the Bermuda College, the Dockyard and the

Maritime Museum before the party came back across the Sound by boat, accompanied by thirty or forty smaller craft. There was then a visit to the Yacht Club and, finally, to the Botanical Gardens for an entertainment by the young people of the Island.

That evening there was a banquet at Government House. Twenty-eight people sat round the main table which took up the whole length of the dining room, and thirty more guests sat at three tables on the terrace. A string quartet played as we ate iced tomato soup, medallions of beef stuffed with stilton cheese and brandy snap baskets with butterscotch mousse and fresh fruits. There were no speeches apart from my few words before the loyal toast, and the evening was rounded off with the regimental band beating the retreat on the front lawn. When it was over I told my aide-de-camp to ask the band to wait so that Prince Philip could thank them on behalf of the Queen, but Eddie had difficulty disentangling himself from the royal party and he did not catch up with the band until well down Langton Hill, the best part of a mile from Government House. Unabashed Eddie ordered an about turn and the band marched back up the hill for a ‘Thank you’ which I suspect the members thought they could have been spared.

The next morning had been planned as an opportunity for the Queen to thank those who had worked on the visit. Some were lucky enough to receive honours and I was particularly lucky to be made a Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order (GCVO). The insignia included a collar of gold which I was told had to be returned on my demise and which the Duke of Edinburgh stressed I would seldom have the opportunity to wear; ‘collar days’, as they are called, being rare events.

Prince Philip was not going back to England with the Queen. He was due to set off for the Caribbean in the afternoon. But when it came to the Queen’s departure he got into the Daimler as well. ‘What are you coming for?’ said the Queen. ‘I am going to see you off’ replied

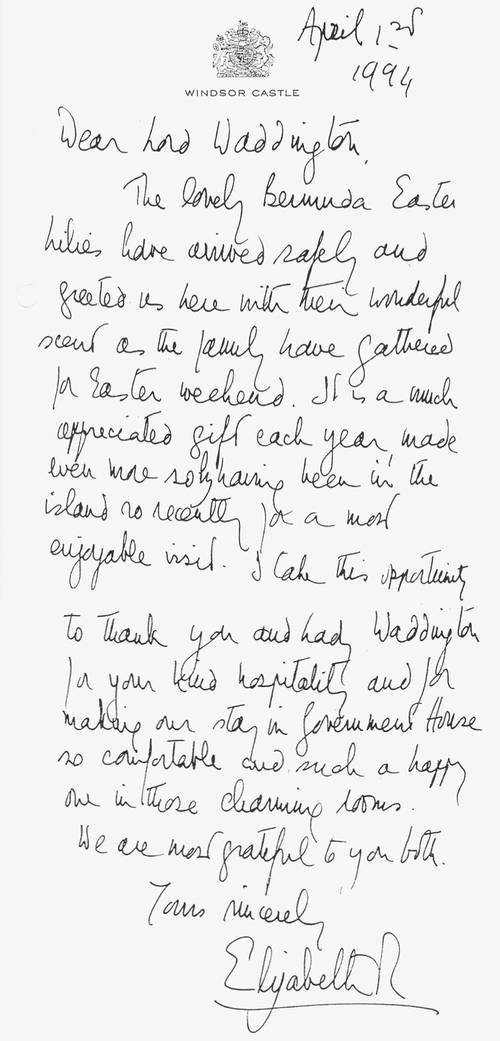

Prince Philip. ‘That’s jolly kind of you,’ said the Queen. And off they went, with plenty of people at the roadside to cheer them on their way. As usual we sent the Queen lilies at Easter and received a lovely letter thanking us for them and for the stay at Government House.