David Waddington Memoirs (24 page)

Read David Waddington Memoirs Online

Authors: David Waddington

It was not unreasonable to expect members of the Cabinet to vote for the Prime Minister and on the day I think they did. But earlier there had been rumours that there were senior Whips asserting the right to vote against her, which I thought was quite extraordinary. A firmer hand there and elsewhere in the Party, appealing for the loyalty which members of the Whips Office owed her, might have garnered the few votes necessary for her to win in the first round. But she failed to do so – by just four votes.

That night John MacGregor, Leader of the House, told me that he doubted whether the Prime Minister could win the second ballot. There were already stories of people who had so far kept their heads down now being prepared to come out for Heseltine. The next day, when I was away from London at a conference in Oxford,

it was determined, I know not by whom, that every member of the Cabinet should have the opportunity to see the Prime Minister on his own and tell her his views. It was a barmy way of trying to determine whether a Prime Minister should stay in office and it would have been far more appropriate for the Cabinet to have met as one body. But the upshot was that when I got back to London and went round to the Prime Minister’s room I found a queue at the door. At that moment Tom King was putting forward a weird idea that the Prime Minister should fight on but announce that if she was re-elected she would bow out in about March. Then out of the room came Chris Patten nursing his bottom like a naughty schoolboy who had been flogged by his headteacher. That did not endear him to some present.

In with the Prime Minister were Ken Baker, Party Chairman, and John Wakeham, who was going to be Margaret’s campaign manager for the second round, if a second round there was going to be. Sitting on a sofa, Margaret looked thoroughly miserable. I had never seen her look like that before. I told her that she knew she could rely on my support if she fought on, but I had my own doubts as to whether she would win – or win

convincingly

enough to make it possible for her to continue in office. It was plain from her reply that she had already made up her mind to go. ‘Isn’t it unfair?’ she said. ‘I’ll be sitting up all night preparing my speech for the censure debate when it will all be completely pointless.’

I sat for a while but, feeling so sad and distressed at the state to which she had been brought by people who, in my view, owed her loyalty and thanks for the great service she had done for the country, I felt I was doing no good there and left.

Early on the Thursday morning John Patten phoned. Douglas Hurd wanted me to propose him for the leadership. I told him I could not. I thought it had been a privilege to serve under

Douglas in the Home Office and knew him to be a man of great integrity and intellect, but I knew that John Major was Margaret’s choice to succeed her and I was not in a mood, after all that had happened, to deny her what little consolation she might get from seeing the man she preferred become leader in her stead. I know that a number of other colleagues voted for John Major for the same reason.

When I got to No. 10 for the Thursday Cabinet meeting Norman Lamont asked me to nominate John Major. I told him that just then I could not bring myself to nominate anybody, but he could take it that in due course I would come out for John. In the Cabinet Room the Prime Minister began to read out the

statement

that was going to be released to the press, but she could not continue. James Mackay asked her if she would like him to read it for her, and at that she pulled herself together and said she could manage. By that time I was not the only one round the table close to tears, but eventually she got it all out. It read:

Having consulted widely among colleagues, I have concluded that the unity of the Party and the prospects of victory in a general election would be better served if I stood down to enable Cabinet colleagues to enter the ballot for the leadership. I should like to thank all those in Cabinet and outside who have given me much dedicated support.

The Lord Chancellor then read a statement expressing the regret of the whole Cabinet and paying tribute to her enormous

achievements

. Douglas Hurd added a few words, as did Kenneth Baker. The normal business of Cabinet followed, and after reading out the business in the Commons for the following week, the Chief Whip finished by saying that the Prime Minister would have great sympathy at Question Time that day. At that Margaret

recovered her old spirit and said with a snort: ‘I prefer the business to the sympathy.’

That afternoon the Prime Minister delivered a speech in the censure debate which made her opponents look like novices. She enjoyed herself hugely as she tore the Opposition motion to pieces. Many who had so recently voted against her must have wondered how on earth they could have come to do it and what hope there could possibly be of the Conservative Party throwing up another leader with the same mastery of the House of Commons. Shortly afterwards, Norman Lamont rang to say that Norman Tebbit was thinking of standing. I rang Norman Tebbit and told him that in my view it would be a great mistake for him to do so. He would find it far more difficult than Douglas or John to unite the Party and, by standing, would harm John’s chances. Norman replied that if he stood John would come last. He would think about what I had said but he did not like John Major’s views on Europe and abhorred Douglas’s.

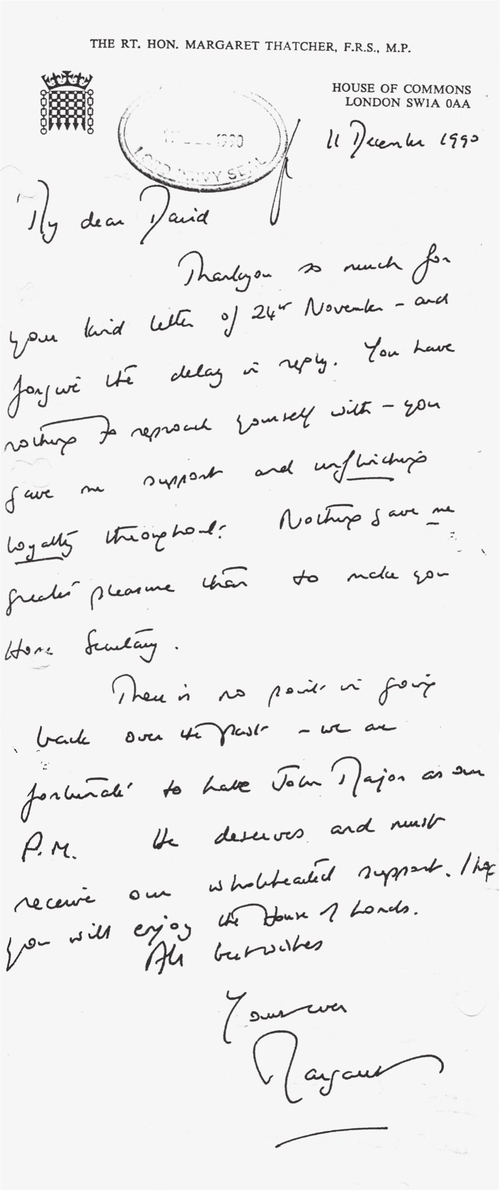

On the Friday evening I went up to Manchester and spoke to the Withington Conservative Association. The chairman decided to conduct a leadership poll there and then, and John Major came out way in front. On the Saturday I was asked by the Major camp if I would declare my support for him on the following day. They had been keeping up the momentum of the campaign by each day getting a prominent member of the Party to say they were for Major, and I agreed to be next in line. I wrote to Margaret thanking her for everything and saying that I was sorry that ambition had led me to accept her invitation to leave the Whips Office and become Home Secretary. I could not help wondering whether, if I had remained in the job, she would have lost hers. I would have made pretty sure that the whips knew they had an obligation of loyalty to her and would have spread the same message among the backbenchers. She wrote back a very touching and generous letter in which she said I had nothing to reproach myself for. But I have never ceased to do so.

A review of her book

The Downing Street Years

contained this passage:

One mystery remains. In her early years as Prime Minister Lady Thatcher was isolated in her own party and Cabinet: she was almost the only true Thatcherite. But more than a decade later the same remained true. Her last Cabinet contained only four

genuine

Thatcherites: David Waddington, Peter Lilley, Cecil Parkinson and, possibly, Michael Howard. Either she had systematically failed to promote Thatcherites up through the ministerial ranks, or she had failed to rally enough Tory Members of Parliament to her cause. These memoirs throw no light on this central question. Lady Thatcher seems willfully to resist it, as though frightened of its larger implications.

I am not sure that I can solve the mystery, but it is worth

remembering

that it was not always very comfortable to be a declared Thatcherite. In public it was far easier to portray oneself as part of the moderate centre, ever questioning the Prime Minister’s decisions, always guarding the party’s conscience, ever showing the compassion which it could be hinted ‘the leader’, for all her virtues, lacked.

Margaret Thatcher was not an easy woman to work with. On most matters she was convinced she was right, and that could be very irritating. But who can blame her for thinking herself right? She usually was. Three hundred and sixty-four economists said her economic policies could not work, but no sooner was the ink dry on their opinions than the policies were seen to be working. The Ministry of Defence doubted whether the Falklands could be retaken. She said they had to be, and they were. Everyone said that the government could not beat the miners. They were far too powerful. Margaret Thatcher knew better. She took them on and she won. The Chancellor of the Exchequer and the Treasury told

her that Britain had to enter the exchange-rate mechanism. She felt in her bones it would end in tears and it did.

It is said that over the poll tax her political antennae failed her and she was over-committed before she realised that retreat was essential for her survival. I do not believe that the idea of a flat-rate charge for local services with rebates for those on low incomes sank her. I do think she failed to realise how grievously Treasury policy was affecting the level of the charge and, therefore, its acceptability. It was, however, her disagreements with the Foreign Office and the Treasury over European policy which provoked Geoffrey Howe’s resignation and it was Geoffrey Howe’s resignation which led to the leadership contest; and I have not the slightest doubt that over Europe she was right and the others wrong. In her refusal to go along with the pretence that Britain could continue to cede more and more power to the European Union – even to the extent of joining a European currency union and losing control of our own economic policy – and yet still remain an independent nation state, she was certainly more honest than her critics.

Margaret Thatcher was tough and did not suffer fools gladly. Diplomacy was not her strong point and the word ‘compromise’ did not feature large in her vocabulary. She knew what she wanted and she expected her ministers to deliver. Convincing her of a case was hard work. She tried to test your arguments to destruction, but when eventually convinced that what you wanted was right she supported you all the way. Indeed, so keen was she to show that support that she often attracted to herself the odium for unpopular policies when lesser Prime Ministers would have made sure it stuck firmly to their subordinates. So it was with the poll tax. Margaret Thatcher had great qualities of leadership which stood the country in good stead at times of crisis, and she was a giant on the world stage. It was sometimes difficult to describe her without using adjectives more familiar to the reader of

Jane’s Fighting Ships

than

the student of political biography – indefatigable, indomitable, intrepid and courageous.

Her determination to resist every threat to peace from the Soviet bloc, her willingness to face any amount of unpopularity at home in order to see her own country properly defended and the West secure, led to the deployment of the Cruise missile in Britain as a response to the Soviet deployment of the SS20 and to the massive build-up of forces behind the iron curtain. That in turn gave her the moral authority to speak for the west and made the Soviets realise that they had no hope with their own far more limited resources of forever preventing democracy in Eastern Europe, let alone

extending

their particular brand of tyranny further west.

When she was first Prime Minister Britain had lost her empire and was no longer a great power, but when she met George Bush Snr at the time of Kuwait there was no doubt who was the boss. ‘All right, George, all right,’ she is reputed to have said; ‘but this is no time to go wobbly.’ I doubt somewhat whether Tony Blair ever felt in a position to address an American President in such terms; and I fear it is inconceivable that David Cameron will ever speak in such terms to Obama or whoever succeeds him.

The trouble with high political office is that it is very difficult to leave it with dignity. Against the odds, Margaret Thatcher did just that. The British people owe her an immense debt and history will be kind to her.

It has no need to be kind to me. I felt that by leaving the Whips Office I had helped to bring about her downfall.

O

n the evening of 27 November, John Major became leader of the Conservative Party. As soon as I had heard the news I had to leave for a dinner at which I was the guest of honour. I made my speech and then was passed a message. I had to go to No. 11 Downing Street at once. I went so fast that I got there before John Major who was still in the House of Commons for the ten o’clock division. Norma was at home and, having offered me a drink, invited me to sit at the end of their bed and watch on television the scenes in the House as John was congratulated by all and sundry. Eventually he arrived at No. 11 and, having talked for a little while on our own, we were joined by Andrew Turnbull and the Cabinet Secretary. We had a long conversation about who might fill various jobs and what I might do and, eventually, he offered and I accepted the leadership of the House of Lords. If I had had any sense I should have stuck out for remaining Home Secretary where my work was only half done, but I sensed that John wanted a change and I got it into my head that going to the Lords would be a more worthwhile challenge than stepping down from the Home Office and becoming, say, Leader of the Commons. I was wrong and I think my judgement was affected by the stressful time we had been through as a result of Margaret’s departure.

Next morning I saw John at No. 10 after he had returned from the Palace. After chatting about other changes he said that

he wanted Lord Denham (Bertie) replaced as Chief Whip by Alexander Hesketh, but I soon persuaded him that it would be a mistake to hurry the change. Bertie had said that he wanted to go in the spring in any event and the sensible course was to wait until then rather than make two key changes at the same time.

I went back to the Home Office to pack up my belongings, and some of the trappings of office of one of Her Majesty’s principal Secretaries of State were then removed with astonishing rapidity. As soon as my move was made public I was told that my detectives were leaving as there were not considered to be any security problems connected with my new post. The next morning I went to the Palace and the Queen gave me framed photographs of herself and Prince Philip.

The next few days I spent in a state of black despair. I felt that in taking the job in the Lords I had let myself down badly. The children, not surprisingly, were not at all interested in becoming ‘Hons.’, and Gilly, whom I had expected to be delighted, was

doubtful

whether I had done the right thing. We went to a wedding and got stuck in a snow drift and I could not help thinking how nice it had been to be driven everywhere by the police. Gilly put a brave face on it publicly, telling the local paper: ‘David finished his job as Home Secretary a success. He is still in the Cabinet and instead of sitting opposite the Prime Minister, he will now be sitting next to him.’ But she then had to cope with the death of her mother, and both of us were miserable.

My move was, however, quite well received by the national press. Simon Heffer in the

Daily Telegraph

wrote:

Mr Waddington’s imaginative appointment as Leader of the Lords is a great bonus. As a minister of long and varied experience and as a former Chief Whip, he should be able to defuse some of the myriad difficulties the government faces in the Lords, where its natural majority all too often acts against it.

One small consolation was the Leader of the Lords’ magnificent room directly over the peers’ entrance in Old Palace Yard; but my first job was not to get my feet under the desk, but my bottom on the red benches. This involved choosing a title and being

introduced

into the Lords as soon as possible. It did not take me long to settle on Waddington, of Read in the County of Lancashire; and Garter King of Arms did a fine job hastening on the formalities so that the introduction could take place before Christmas.

This was how the scene was described in the

Lancashire Evening Post

:

The 61-year-old Burnley-born Tory made none of the fuss that Baroness Castle caused when she was initiated as a life member of the aristocracy a year ago. There was no repeat of her objections to the red and ermine robes or her point blank refusal to wear and doff her hat.

Mr Waddington, the typical Tory officer and gentleman, was the soul of obedience and respect for tradition. At just after 2.30 p.m. he was led in by Black Rod – Air Vice-Marshall Sir John Gyngell and Garter King of Arms, Sir Colin Cole. His prime supporter, government Chief Whip Lord (Bertie) Denham, and his secondary supporter, Lord Carlisle of Bucklow – former Education Secretary Mark Carlisle – followed three paces behind. With an audience which included Baroness Castle in an autumn print dress, former Prime Minister Lord Callaghan in a grey suit and ex-Lord Chancellor Lord Hailsham with his inevitable stick, the three made their stately pace through the red and gold splendour of the Lords. The words that established the new Lord Waddington as a trusty counsellor of the Queen were read and he shook hands with the Lord Chancellor, Lord Mackay of Clashfern. Nodding his head in the direction of the Queen’s chairman of the Lords, Baron Waddington and his supporters processed round

the Chamber. They then took their seats at the side and respectfully put on their black hats, which date from the era when Wellington won Waterloo. With Garter King of Arms facing them, they doffed their archaic headgear three times to Lord Mackay, rose and, once more led by Black Rod, processed out of the Chamber. Mr Waddington – barrister and former Crown Court recorder of true Lancashire mill-owning stock – was now a peer of the realm for life.

I then got a bill from Garter King of Arms for £1,630, the fee for a grant of armorial bearings with supporters. The covering letter read like double dutch: ‘You might care to suggest the tinctures which you would like to see employed and also such symbols and devices as are of appeal to you and would look well upon your shield or forming the crest.’

I soon discovered that my new job was far from taxing. Most mornings there was virtually nothing to do. I would call my private secretary and ask her to bring in some work and after a while one letter would appear and a notice of a meeting of the Dorneywood Trust of which I was chairman. If I had remained Home Secretary, I would probably have been about to occupy Dorneywood. Instead I was told, as if a great prize was being bestowed on me, that I could stay in South Eaton Place which I heartily loathed. John Major had told me that, as Leader, I would be his right-hand man, but within a matter of weeks it was obvious that that was not going to be the case – through no fault of the Prime Minister. Ninety per cent of the business management problems of the government were House of Commons problems and what happened in the Lords was small beer. Furthermore, with a general election not all that far off the Party Chairman’s role was of great importance and time and again, when I saw the Prime Minister with John MacGregor (the new Leader of the House of Commons) on a Monday, our meeting

lasted only a few minutes because the matters the Prime Minister thought important had already been covered in an earlier meeting with Chris Patten, the new Party Chairman.

I had to make my maiden speech from the dispatch box. Lord Elton initiated a debate on sentencing policy which gave me the opportunity to talk of the Criminal Justice Bill which I had

introduced

in the Commons the previous month. The debate was like most of those I had to listen to as Leader – well informed but

sleep-inducing

– with the Tory peers as critical of the government as the Opposition. Six former Home Office ministers spoke after me and a former permanent secretary; and I soon discovered that even in those days, when the hereditary peers far outnumbered the lifers, nearly all who took part in important debates had had distinguished careers in industry, the academic world or public service and made really

well-informed

contributions. Peers did not queue up at the Whips Office asking for a one-page brief on a subject down for debate, as

sometimes

happens in the Commons. Whips did not go around the place asking people to speak in order to keep a debate going until the hour at which a division had been arranged, as also happens in the Commons. People who knew what they were talking about put their names down to speak and their records entitled them to be listened to with respect. When I opened a debate during the Gulf War I was followed by two Field Marshals and after that experience I did not think I knew all there was to know about warfare.

Question Time I found a worry. It was not often that I had to answer any questions myself but I had to sit on the front bench worrying about the performance of others. There were few

departmental

ministers in the Lords, certainly not one in every

department

, so very often questions had to be answered by the Whips (entitled ‘Lords in Waiting’). They did their best to mug up on subjects raised but they were either not particularly well briefed by the government department concerned (departments attached

little importance to what was going on in the Lords) or they were not skilled enough to know what extra briefing they needed. As a result, they were always at risk of being caught out. Andrew Davidson, the deputy Chief Whip, provided a briefing for new whips in biblical language, part of which read: ‘A Lord in waiting should stick to his brief. The further he strayeth from it, the deeper the pit he diggeth for himself to fall into; and if he knoweth not the answer, he should say so but not too often.’

In February 1991 there was the mortar attack on Downing Street. My room in the Privy Council Office overlooked Downing Street and I could see from my desk the usual group of photographers outside No. 10. Suddenly there was a loud bang and a cloud of black smoke rose above the roof of No. 12. I rushed down the stairs and out into the street and hammered on the door of No. 10. When I got inside a number of people were coming through the

connecting

door from No. 11. Nobody seemed to be injured and as there was nothing useful I could do, I went back into Downing Street and had a somewhat inconsequential conversation with a chap carrying a television camera on his shoulder. I was mightily surprised when I saw the news that night and found the whole conversation had been filmed. No harm had been done but I should have taken more care. I repeated in the Lords the statement on the incident made by Kenneth Baker in the Commons.

Gilly’s father died in February. He could have been a great poet and would, I think, have made a more successful poet than he was a politician. He was a very intelligent man but his plain speaking, his refusal to suffer fools and his determination to fight marginal seats in Lancashire rather than seek a safe haven further south ruined his chances of rising as high as he deserved in government. His death left us a load of trouble. Under his will Whins House, where we had lived since 1965, had been left to Gilly and her two sisters equally so we could only stay there if we bought out her sisters.

We could not buy them out by selling our own house, The Stables, where the Greens had been living, because we would have had to pay a vast sum in capital gains tax as a result of The Stables not having been our residence. So a family arrangement made with the best will in the world twenty-five years earlier (the swapping of the two houses without transferring ownership) turned out to have been a monumental blunder. Eventually, we decided to do up The Stables and go back there. Gilly made a marvellous job of the alterations and it turned out all right in the end.

I was very worried as to what was going to happen in the by-election caused by my elevation. My advice to the Ribble Valley Association was that they should pick someone with previous parliamentary experience and local connections. There was only one person who fitted the bill, Derek Spencer, whose parents had a farm in Waddington, and he would have been excellent. The Association, however, thought nothing of my advice. They saw Derek and thought him boring, and chose a very worthy young Welshman, Nigel Evans. Nigel has, since 1992, served Ribble Valley extremely well, but he was a strange choice for a by-election in the middle of a parliament when even a local person was going to have an uphill struggle. The by-election came – and my 19,000 majority went down the chute. I had precipitated the by-election, I had lost it for the Party and what had I got in return? The leadership of a House in which one’s own side had little idea of party loyalty and no compunction about embarrassing the government they had pledged themselves to support. I felt like cutting my throat.

There were some moments that brought me cheer. In the spring of 1991 Mikey Strathmore

*

asked me if I would give a cocktail party in my room in honour of Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother who, being a relation of his, was coming to dine in the Lords’ Dining Room. Queen

Elizabeth arrived with her private secretary, Sir Martyn Gilliatt. It was rather hot and I thought Sir Martyn looked a bit vacant. The next moment he fell as if poleaxed. I thought he was dead. A number of people gathered round, someone went out to find a doctor. Queen Elizabeth, looking down kindly on him, said: ‘He’s always doing that,’ and then carried on chatting with those around her.

I mentioned earlier that when Home Secretary I reintroduced the War Crimes Bill and saw it carried through the House of Commons for a second time with little dissent. On 30 April 1991, I had to move the second reading in the Lords. The Bill was word for word the same as the one the Lords had rejected in 1990. This was intentional. If it had been different in any material respect then, on rejection by the Lords, the Parliament Act would not have applied and the Bill would not automatically have become law. But the fact that the Bill was in the same terms did not mean that the government had made up its mind in advance to reject any amendments. I made this abundantly plain in my opening speech,

*

and it was absolutely obvious to me, and ought to have been just as obvious to the House, that it was in the interests of opponents of the Bill to give it a second reading. If it was rejected at second reading, it would become law immediately – warts and all. If, on the other hand, it got a second reading, the House would then have endless opportunities to either improve it by amendment or harass the government throughout a long hot summer and hope that eventually it would feel it had better things to do with its time.