CSS: The Definitive Guide, 3rd Edition (22 page)

Read CSS: The Definitive Guide, 3rd Edition Online

Authors: Eric A. Meyer

Tags: #COMPUTERS / Web / Page Design

Now let's look at ways to manipulate the capitalization

of text using the propertytext-transform.

text-transform

- Values:

uppercase|lowercase|capitalize|none|inherit- Initial value:

none- Applies to:

All elements

- Inherited:

Yes

- Computed value:

As specified

The default valuenoneleaves the text alone and

uses whatever capitalization exists in the source document. As their names imply,uppercaseandlowercaseconvert text into all upper- or lowercase characters. Finally,capitalizecapitalizes only the first letter of

each word.

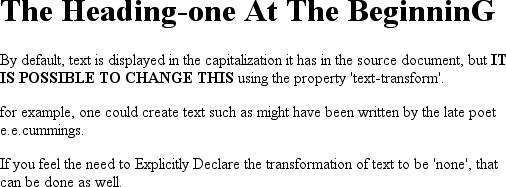

Figure 6-24

illustrates each of

these settings in a variety of ways:

h1 {text-transform: capitalize;}

strong {text-transform: uppercase;}

p.cummings {text-transform: lowercase;}

p.raw {text-transform: none;}

The heading-one at the beginninG

By default, text is displayed in the capitalization it has in the source

document, but it is possible to change this using

the property 'text-transform'.

For example, one could Create TEXT such as might have been Written by

the late Poet e.e.cummings.

If you feel the need to Explicitly Declare the transformation of text

to be 'none', that can be done as well.

Figure 6-24. Various kinds of text transformation

Different user agents may have different ways of deciding where words begin and, as a

result, which letters are capitalized. For example, the text "heading-one" in theh1element, shown in

Figure 6-24

, could be rendered in one of two

ways: "Heading-one" or "Heading-One." CSS does not say which is correct, so either is

possible.

You probably also noticed that the last letter in theh1element in

Figure 6-24

is

still uppercase. This is correct: when applying atext-transformofcapitalize, CSS only

requires user agents to make sure the first letter of each word is capitalized. They can

ignore the rest of the word.

As a property,text-transformmay seem minor, but

it's very useful if you suddenly decide to capitalize all yourh1elements. Instead of individually changing the content of all yourh1elements, you can just usetext-transformto make the change for you:

h1 {text-transform: uppercase;}

This is an H1 element

The advantages of usingtext-transformare

twofold. First, you only need to write a single rule to make this change, rather than

changing theh1itself. Second, if you decide later

to switch from all capitals back to initial capitals, the change is even easier, as

Figure 6-25

shows:

h1 {text-transform: capitalize;}

This is an H1 element

Figure 6-25. Transforming an H1 element

Next we come totext-decoration, which is a fascinating property that

offers a whole truckload of interesting behaviors.

text-decoration

- Values:

none| [underline||overline||line-through||blink] |inherit- Initial value:

none- Applies to:

All elements

- Inherited:

No

- Computed value:

As specified

As you might expect,underlinecauses an element

to be underlined, just like theUelement in HTML.overlinecauses the opposite effect—drawing a line

across the top of the text. The valueline-throughdraws a line straight through the middle of the text, which is also known as

strikethrough text

and is equivalent to theSandstrikeelements in

HTML.blinkcauses the text to blink on and off, just

like the much-malignedblinktag supported by

Netscape.

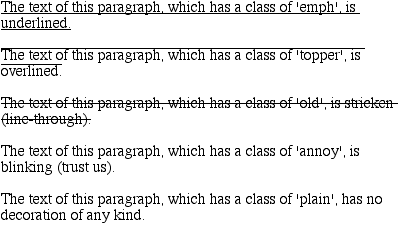

Figure 6-26

shows examples of each

of these values:

p.emph {text-decoration: underline;}

p.topper {text-decoration: overline;}

p.old {text-decoration: line-through;}

p.annoy {text-decoration: blink;}

p.plain {text-decoration: none;}

Figure 6-26. Various kinds of text decoration

It's impossible to show the effect ofblinkin

print, of course, but it's easy enough to imagine (perhaps all too easy).

Incidentally, user agents are not required to supportblink, and as of this writing, Internet Explorer never has.

The valuenoneturns off any decoration that might

otherwise have been applied to an element. Usually, undecorated text is the default

appearance, but not always. For example, links are usually underlined by default. If you

want to suppress the underlining

of hyperlinks,

you can use the following CSS rule to do so:

a {text-decoration: none;}

If you explicitly turn off link underlining with this sort of rule, the only visual

difference between the anchors and normal text will be their color (at least by default,

though there's no ironclad guarantee that there will be a difference in their colors).

Although I personally don't have a problem with it, many users are annoyed when

they realize you've turned off link underlining. It's a matter of opinion, so let

your own tastes be your guide, but remember: if your link colors aren't sufficiently

different from normal text, users may have a hard time finding hyperlinks in your

documents.

You can also combine decorations in a single rule. If you want all hyperlinks to be

both underlined and overlined, the rule is:

a:link, a:visited {text-decoration: underline overline;}

Be careful, though: if you have two different decorations matched to the same

element, the value of the rule that wins out will completely replace the value of the

loser. Consider:

h2.stricken {text-decoration: line-through;}

h2 {text-decoration: underline overline;}

Given these rules, anyh2element with a class ofstrickenwill have only a line-through decoration.

The underline and overline decorations are lost, since shorthand values replace one

another instead of accumulating.

Now, let's look into the unusual side oftext-decoration. The first oddity is thattext-decorationis

not

inherited.

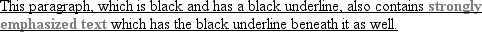

No inheritance implies that any decoration lines drawn with the text—under, over, or

through it—will be the same color as the parent element. This is true even if the

descendant elements are a different color, as depicted in

Figure 6-27

:

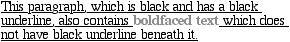

p {text-decoration: underline; color: black;}

strong {color: gray;}

This paragraph, which is black and has a black underline, also contains

strongly emphasized text which has the black underline

beneath it as well.

Figure 6-27. Color consistency in underlines

Why is this so? Because the value oftext-decorationis not inherited, thestrongelement assumes a default value ofnone. Therefore, thestrongelement has

no

underline. Now, there is very clearly a line under thestrongelement, so it seems silly to say that

it has none. Nevertheless, it doesn't. What you see under thestrongelement is the paragraph's underline, which is

effectively "spanning" thestrongelement. You can

see it more clearly if you alter the styles for the boldface element, like this:

p {text-decoration: underline; color: black;}

strong {color: gray; text-decoration: none;}

This paragraph, which is black and has a black underline, also contains

strongly emphasized text which has the black underline beneath it as

well.

The result is identical to the one shown in

Figure 6-27

, since all you've done is to explicitly declare what was

already the case. In other words, there is no way to turn off underlining

(or

overlining or a line-through) generated by a parent element.

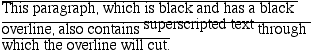

Whentext-decorationis combined withvertical-align, even stranger things can happen.

Figure 6-28

shows one of these oddities.

Since thesupelement has no decoration of its

own, but it is elevated within an overlined element, the overline cuts through the

middle of thesupelement:

p {text-decoration: overline; font-size: 12pt;}

sup {vertical-align: 50%; font-size: 12pt;}

Figure 6-28. Correct, although strange, decorative behavior

By now you may be vowing never to use text decorations because of all the problems

they could create. In fact, I've given you the simplest possible outcomes since we've

explored only the way things

should

work according to the

specification. In reality, some web browsers do turn off underlining in child

elements, even though they aren't supposed to. The reason browsers violate the

specification is simple enough: author expectations. Consider this markup:

p {text-decoration: underline; color: black;}

strong {color: silver; text-decoration: none;}

This paragraph, which is black and has a black underline, also contains

boldfaced text which does not have black underline

beneath it.

Figure 6-29

shows the display in a web

browser that has switched off the underlining for thestrongelement.

Figure 6-29. How some browsers really behave

The caveat here is that many browsers

do

follow the

specification, and future versions of existing browsers (or any other user agents)

might one day follow the specification precisely. If you depend on usingnoneto suppress decorations, it's important to realize

that it may come back to haunt you in the future, or even cause you problems in the

present. Then again, future versions of CSS may include the means to turn off

decorations without usingnoneincorrectly, so

maybe there's hope.

There is a way to change the color of

a decoration without violating the specification. As

you'll recall, setting a text decoration on an element means that the entire element

has the same color decoration, even if there are child elements of different colors.

To match the decoration color with an element, you must explicitly declare its

decoration, as follows:

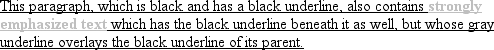

p {text-decoration: underline; color: black;}

strong {color: silver; text-decoration: underline;}

This paragraph, which is black and has a black underline, also contains

strongly emphasized text which has the black underline

beneath it as well, but whose gray underline overlays the black underline

of its parent.

In

Figure 6-30

, thestrongelement is set to be gray and to have an

underline. The gray underline visually "overwrites" the parent's black underline, so

the decoration's color matches the color of thestrongelement.

Figure 6-30. Overcoming the default behavior of underlines