Conservatives Without Conscience (33 page)

Read Conservatives Without Conscience Online

Authors: John W. Dean

Tags: #Politics and government, #Current Events, #Political Ideologies, #International Relations, #Republican Party (U.S. : 1854- ), #Political Process, #2001-, #General, #United States, #Conservatism & Liberalism, #Conservatism, #Political Science, #Political Process - Political Parties, #Politics, #Political Parties, #Political Ideologies - Conservatism & Liberalism

16.

In a December 18, 2005, speech, President Bush all but conceded the point that America is provoking terror. He stated, “If you think the terrorist would become peaceful if only America would stop provoking them, then it might make sense to leave them alone.” George W. Bush, “Bush Says Iraqis See Democracy as Their Future,” U.S. Department of State, at http://usinfo.state.gov/mena/Archive/2005/Dec/19-15664.html. Writing in the

Yale Law Journal,

Jeffery Manns discusses the reality that American foreign policy’s provocation of terrorism requires the government to help with insurance coverage of terrorist activity. Jeffery Manns, “Insuring Against Terror?”

Yale Law Journal,

vol. 112:8 (2003). Philip C. Wilcox, president of the Foundation for Middle East Peace, asserted, “The administration has focused on the destruction of terrorists and terrorist groups as the solution to terrorism. Certainly, we must do this, but terrorism is a symptom of deeper conflicts. If destroying terrorists is all we do, it’s only a palliative. Unless we understand, try to eliminate or at least contain the problems that breed terrorism, we’re going to fail, and the virus of terrorism will continue to grow

and spread. Some have called this approach appeasement, but it’s not. It’s common sense. Iraq is emerging to surprise the administration, as a new breeding ground for terrorism that didn’t exist previously.” Philip C. Wilcox, Jr., “Imperial Dreams: Can the Middle East Be Transformed?,”

Middle East Policy,

vol. 10 (Winter 2003), 1.

17.

Athan G. Theoharis and John Stuart Cox,

The Boss: J. Edgar Hoover and the Great American Inquisition

(Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1988), 102.

18.

See, e.g., Curt Gentry,

J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets

(New York: W. W. Norton, 1991); Athan Theoharis,

The FBI & American Democracy: A Brief Critical History

(Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2004); William C. Sullivan with Bill Brown,

The Bureau: My Thirty Years in Hoover’s FBI

(New York: W. W. Norton, 1979); and Anthony Summers,

Official and Confidential: The Secret Life of J. Edgar Hoover

(New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1993).

19.

Sullivan with Brown,

The Bureau,

136–37.

20.

Summers,

Official and Confidential,

434.

21.

Paul Johnson,

A History of the American People

(New York: HarperCollins, 1997), 837.

22.

Jonathan M. Schoenwald,

A Time for Choosing: The Rise of Modern American Conservatism

(New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 48.

23.

Sullivan with Brown,

The Bureau,

49. Sullivan documented the Kennedy situation. I have personal knowledge of the Nixon situation.

24.

Congressman Dan Burton, a conservative Republican from Indiana, introduced legislation on July 25, 2002 (HR 5213) to rename the FBI headquarters building and remove the name of J. Edgar Hoover from the building. Burton was joined by bipartisan cosponsors: Steven LaTourette (R-OH), Christopher Shays (R-CT), William Delahunt (D-MA), John Lewis (D-GA), and John Tierney (D-MA). Even the

Wall Street Journal

’s editorial pages has called for “stripping J. Edgar Hoover’s name from FBI headquarters.” Anonymous, “A Real Surveillance Scandal,”

Wall Street Journal

(January 10, 2006), A-14.

25.

In a conversation I had with Vice President Agnew in December 1970, he told me of his admiration for Hoover at a time when others in the Nixon White House were trying to get Hoover to resign.

26.

Richard Nixon,

RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon

(New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1978), 411–12.

27.

Facts on File Yearbook 1970

(New York: Facts on File, Inc., 1971), 698.

28.

Terri Bimes, “Reagan: The Soft-Sell Populist,” in W. Elliot Brownlee and Hugh David Graham, eds.,

The Reagan Presidency: Pragmatic Conservatism & Its Legacies

(Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2003), 61.

29.

Richard Reeves,

President Nixon: Alone in the White House

(New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001), 159–60.

30.

This material is drawn largely from Phyllis Schlafly’s Web site at http://www.phyllisschlafly.com/.

31.

Elizabeth Kolbert, “Firebrand: Phyllis Schlafly and the Conservative Revolution,”

The New Yorker

(November 7, 2005) at http://www.newyorker.com/printables/critics/051107crbo_books.

32.

The source of this material is in part the National Women’s Party Web site on the ERA at http://www.equalrightsamendment.org/, and in part Ruth Murray Brown’s book

For a “Christian America”—A History of the Religious Right

(Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2002), 15–62.

33.

Phyllis Schlafly, “Is the Era of Big Government Coming Back?”

The Phyllis Schlafly Report,

vol. 35, no. 7 (February 2002) at http://www.eagleforum.org/psr/202/feb02/psrfeb02.shtml.

34.

John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge,

The Right Nation: Conservative Power in America

(New York: Penguin Press, 2004), 81.

35.

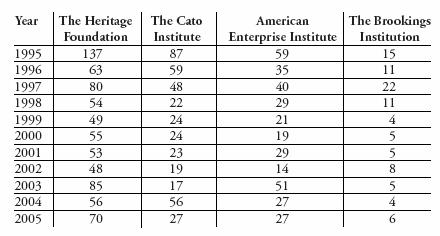

I can remember Richard Nixon grousing, in 1971, that Republicans had but one small think tank, the American Enterprise Institute, which today is also an affluent great-granddaddy. In recent years there has been a proliferation of right-wing think tanks. For example, the Heritage Foundation Web site refers to some 564 experts or organizations espousing conservative views, including the Nixon Center for Peace and Freedom in Washington, D.C. (See the Heritage Foundation, “Policy Experts,” at http://policyexperts.org/organizations/organizations_results.cfm.) Do think tanks matter? Do all their books, position papers, seminars, and briefings influence policy? No definitive answer is possible, for there is no way to measure accurately. Donald E. Abelson,

Do Think Tanks Matter? Assessing the Impact of Public Policy Institutes

(Montreal: McGill–Queen’s University Press, 2002). But clearly they have influence. Former conservative activist and writer David Brock (who had his own eye-opening experiences with conservatism and created the Media Matters for America Web site that puts the lie to conservative misinformation and propaganda) wrote in

The Republican Noise Machine,

“In 1998 Heritage spent close to $8 million, or 18 percent of its budget, on media and government relations.” David Brock,

The Republican Noise Machine: Right-Wing Media and How It Corrupts Democracy

(New York: Crown Publishers, 2004), 58. Spending such sums enables them to keep their name before policy makers, and today conservative think tanks appear to have a far greater influence than moderate ones, even long-established organizations like Brookings. I undertook a rather simple, albeit unscientific, test of the relative strength of the major think tanks on Capitol Hill by noting how often they were referred to on the floor of the House and Senate since 1995. Using the Government Accountability Office’s search engine for the

Congressional Record,

I found the following:

36.

Jean Stefancic and Richard Delgado,

No Mercy: How Conservative Think Tanks and Foundations Changed America’s Social Agenda

(New York: Temple, 1997). Work product of the conservative think tanks, however, has become notably predictable, and they are not generating great ideas; rather, they “produce studies with one or more preordained conclusions: that liberal solutions will only increase the power and oppressiveness of government and bureaucracy; that they deprive worthy citizens of their liberty, or that they benefit criminals at the expense of victims; and, most often, that more laissez-faire and lower taxes for business is always the best policy.” Herbert J. Gans, “Tanking the Right,”

The Nation

(January 27, 1997), 28.

37.

Notes, telephone conversation with Senator Barry M. Goldwater, March 1995.

38.

Barry M. Goldwater with Jack Casserly,

Goldwater

(New York: Doubleday, 1988), 386.

39.

Ralph Z. Hallow, “Weyrich fears ‘cordial’ ties between GOP and the Right,”

Washington Times

(June 17, 2005) at http://www.washingtontimes.com/national/20050617-125248-4355r.htm.

40.

E. J. Dionne, “Roasting the Rightest of the Right; Conservatives Turn Out for Tough Guy Weyrich,”

Washington Post

(April 2, 1991), E-1.

41.

Ibid.

42.

Jeff Jacoby, “The Christian Right’s Double Shocker,”

Boston Globe

(April 26, 2001), A-15.

43.

For example, when Michael Deaver left the Reagan White House to set up a highly lucrative lobbying operation—with Canada, South Korea, Mexico, and Saudi Arabia among his A-list of clients—Paul Weyrich called for a special prosecutor to investigate charges of conflicts of interest. (Martin Tolchin, “Conservatives Say Deaver Case Hurts Reagan,”

New York Times

[May 1,

1986], A-21.) Although he could not back it up with specifics, Weyrich later shot down Bush I’s nomination of Senator John Tower to be Secretary of Defense because he opposed Tower’s alleged drinking and spending time with women “to whom he was not married.” (Suzanne Garment, “The Tower Precedent,”

Commentary

[May 1989], 44.) Weyrich was relentless in his attacks against Bill Clinton. (Anonymous,

New York Times

[November 12, 1995], 6-37.) However, Weyrich wrote thoughtful op-eds critical of conservatives and the Reagan White House, following revelations about the Iran/Contra debacle. He explained that “our government was designed not to play great-power politics but to preserve domestic liberty” through “separation of powers, congressional checks on executive authority, the primacy of law over raison d’état—all of these were intentionally built into our system.” He continued, “The Founding Fathers knew a nation with such a government could not play the role of a great power. They had no such ambition for us—quite the contrary.” Weyrich also raised a problem in 1987 that remains to this day: “If the executive does what it must in the international arena, it violates the domestic rules. If the Congress enforces those rules, as it is supposed to do, it cripples us internationally.” Paul M. Weyrich, “A Conservative Lament; After Iran, We Need to Change Our System and Grand Strategy,”

Washington Post

(March 8, 1987), B-5.

44.

Anonymous,

New York Times

(November 12, 1995), 6-37.

45.

Steve Bruce, “Zealot Politics and Democracy: The Case of the New Christian Right,”

Political Studies,

vol. 48 (2000), 263–82.

46.

Religion scholar Laurence Iannaccone reported that an “enormous multi-year study, sponsored by the American Academy of Arts and Science, and directed by religious historians Martin E. Marty and R. Scott Appleby…enlisted over a hundred researchers to describe and analyze dozens of ‘fundamentalist-like’ movements across five continents and seven religious traditions” to explain fundamentalism. Yet this “Fundamentalism Project,” as it is known, came up with “no clear definition of fundamentalism, no objective criterion for deciding which religious movements are ‘fundamentalist,’ and nothing approaching a

theory

of fundamentalism.” Laurence R. Iannaccone, “Toward an Economic Theory of ‘Fundamentalism,’”

Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics,

vol. 153 (1997), 100. The Fundamentalism Project, to the chagrin of evangelicals, labels them as a fundamentalist religion.

47.

Corine Hegland, “Special Report: Values Voters—Evangelical, Not Fundamentalist,”

National Journal

(December 3, 2004).

48.

Micklethwait and Wooldridge,

The Right Nation,

83.

49.

Special Report, “You Ain’t Seen Nothing Yet,”

Economist

(June 23, 2005) at http://www.economist.com/world/na/PrintFriendly.cfm?story_id=4102212.