Conservatives Without Conscience (30 page)

Read Conservatives Without Conscience Online

Authors: John W. Dean

Tags: #Politics and government, #Current Events, #Political Ideologies, #International Relations, #Republican Party (U.S. : 1854- ), #Political Process, #2001-, #General, #United States, #Conservatism & Liberalism, #Conservatism, #Political Science, #Political Process - Political Parties, #Politics, #Political Parties, #Political Ideologies - Conservatism & Liberalism

26.

Unfortunately, Nash happened to mangle his material and its source regarding this significant point. Nash stated: “On one occasion, Jeffrey Hart of Dartmouth College in effect conceded the Declaration to the liberals. He then insisted that its doctrine was not theory of the Constitution, whose Preamble had conspicuously failed to list ‘rights’ or ‘equality’ among the purposes of the new government of 1788. There were, in fact, two theories of government present in the Revolutionary War period, and liberals could

claim only one of them.” Nash cited John Hallowell,

American Political Science Review,

vol. 58 (September 1964), 687. However, the Hallowell book review to which Nash refers makes no mention of Jeffrey Hart, who had a very interesting read on the Declaration. He said, “I regard the Declaration of Independence as just that, a declaration of independence from England, written by Englishmen in the Colonies to establish their position on a foundation that would be accepted in England. In that context, the phrase ‘all men are created equal’ means that Americans are equal to Englishmen in their capacity for self-government. When we go beyond the Prologue to the list of particulars in the indictment of George III, we have that passage about him inflicting the ‘savage Indian tribes’ upon our frontier settlements, the Indians slaughtering Americans without regard to age or sex. This, I think, ‘de-universalizes’ the ‘all men are created equal’ in capacity for self-government. The Indians were a stone-age people who had not invented the wheel and had no written language.” (E-mail exchange with author.)

27.

Nash,

The Conservative Intellectual Movement in America,

194–95.

28.

Ibid., 207–8.

29.

Ibid. Nash reported “the ever-argumentative” Frank Meyer’s reaction to Jaffa’s position, chiding his fixation with Lincoln’s interpretation of the founding documents. He did not refute Jaffa’s assertion, however.

30.

Ibid., 194.

31.

See Louis Hartz,

The Liberal Tradition in America: An Interpretation of American Political Thought Since the Revolution

(New York: Harcourt Brace, 1955), 308. The progenitors of American conservatism apparently felt compelled to push credulity, because unlike the English and Europeans, Americans did not have to revolt against the feudalism of an ancien régime to gain their freedom; rather, they only had to remove the economic shackles of monarchy. Accordingly, conservatives have simply denigrated America’s founding generation to rid them of their “liberal tradition.” They trivialize the oppressive demands that the distant monarchy placed on the nation’s forebearers, a situation that forced men (and women) who wished to be loyal to the Crown to undertake actions that were anything but conservative by breaking ties with their motherland and fighting a bitter and protracted war of liberation. This is not to say that there was nothing conservative whatsoever about this revolution. One can find strains of conservatism in even the most liberal, radical, or reactionary of actions. While no one would call Joseph Stalin a conservative, his actions in seeking to maintain his power, and that of the Communist Party in Russia, were conservative actions. In the early 1960s, legendary American historian Samuel Eliot Morison wrote, “the principles of the American Revolution were essentially conservative; the leaders were thinking of preserving and securing the freedom they already enjoyed rather than, like the Russians, building some

thing new and different.” Samuel Eliot Morison,

The Oxford History of the American People, Vol. One: Prehistory to 1789

(New York: Meridian, 1994), 355. Morison’s argument is not unlike saying that Stalin was a conservative in seeking to “preserve and secure” communism. While such conservative principles may have been subscribed to by the elite, it is difficult to find them in Tom Paine’s

Common Sense,

which stirred both colonial leaders and followers, or in Paine’s

Crisis,

which rallied many during the war. Early conservative scholars like Morison claimed a conservative tradition for America based on the slimmest of philosophical and historical reeds. It is ironic that conservatives honor tradition, but when that tradition is not quite what they wish, they just rewrite it.

32.

David McCullough,

1776

(New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005), 294.

33.

Federalist Paper No. 14

at http://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/v1ch4s22.html.

34.

Nash,

The Conservative Intellectual Movement in America,

195.

35.

Ibid.

36.

Clinton Rossiter,

Conservatism in America,

2nd ed. (New York: Knopf, 1962), 69, 262. Neoconservatives have claimed Rossiter as one of their own. See Norman Podhoretz, “Neoconservatism: A eulogy,”

Commentary

(March 1996), 19.

37.

This column provided a vehicle for the senator to sharpen his own thinking on the subject. Given his duties in the Senate and his active schedule as a Republican spokesperson, giving talks throughout the country, he enlisted his former campaign manager, Stephen Shadegg—who he knew shared his thinking—to write many of the columns, with the senator suggesting topics and then editing the copy. For his definition of conservatism and conservatives, see Barry Goldwater, “How Do You Stand, Sir?”

Los Angeles Times,

September 27, 1960.

38.

Barry Goldwater,

The Conscience of a Majority

(Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1970), xii.

39.

Barry M. Goldwater with Jack Casserly,

Goldwater

(New York: Doubleday, 1988), 121.

40.

Barry Goldwater,

Conscience of a Conservative

(Shepherdsville, KY: Victor Publishing, 1960), 13.

41.

Notes, telephone conversation with Senator Barry M. Goldwater, March 1995.

42.

Goldwater,

Conscience of a Conservative,

14.

43.

Philip Gold,

Take Back the Right: How the Neocons and the Religious Right Have Betrayed the Conservative Movement

(New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2004), 65.

44.

William Safire, “Inside a Republican Brain,”

New York Times

(July 21, 2004), A-19.

45.

They included the original “triad of

Human Events

for the activists,

Modern Age

for the academics and

National Review

for everybody,” plus “the

American Spectator, Policy Review, Commentary,

the

Weekly Standard, Public Interest, First Things

and

Chronicles.

They also cite religiously oriented journals,

Crisis,

a Catholic monthly, and

World,

an evangelical weekly.” David Wagner, “Who’s Who in America’s Conservative Revolution?”

Insight

(December 23, 1996), 18.

46.

Ibid.

47.

For example, here is a list of the most commonly recurring labels conservatives used to describe themselves (or each other) that I have noted in my research: “traditional conservatives,” “paleoconservatives,” “old right,” “classic liberal conservatives,” “social conservatives,” “cultural conservatives,” “traditional conservatives,” “Christian conservatives,” “fiscal conservatives,” “economic conservatives,” “compassionate conservatives,” “neoconservatives,” and “libertarians.”

48.

Poll numbers were not easy to come by, but after posting an inquiry on Josh Marshall’s TPM Café, thanks to a blog reader identified only as “uc,” I located what appears to be the most recently published breakdown in, of all places, the

Mortgage News

(February, 17, 2005). See http://www.tpmcafe.com/author/J%20Dean.

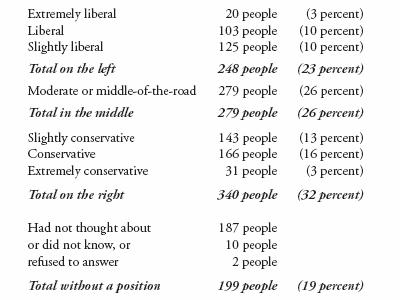

49.

William A. Galston and Elaine C. Kamarck, “The Politics of Polarization,”

The Third Way Middle Class Project

(October 2005), Table 15, “Ideological self-identification of the U.S. electorate, 1976–2004,” 42. Political scientist Kenneth Janda, who examined the left-right placement responses to the 2004 National Election Survey—widely considered by academics as being among the most reliable numbers gathered—provided me with a general overview of the nation’s political leanings after the 2004 election. Here I have focused only on the postelection numbers (which are very similar to the preelection responses) of the 1,006 (randomly selected) people who responded to the following question: “We hear a lot of talk these days about liberals and conservatives. Here is a seven-point scale on which the political views that people might hold are arranged from extremely liberal to extremely conservative. Where would you place

YOURSELF

on this scale, or haven’t you thought much about this?” The responses were:

50.

Brian Mitchell, “Bush Spending Yet to Alienate the Hard Core,”

Mortgage News

(February 17, 2004) at http://www.home-equity-loans-center.com/Mortgage2_14__04/News6.htm.

51.

This conclusion is justified by extrapolation from other polling data, and none of these conservative subgroups appear to exceed 10 percent. For example, the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press has polled different types of political attitudes, and has divided Republicans into three groups: “Enterprisers,” who are extremely partisan and deep believers in the free-enterprise system, whose social values reflect a conservative agenda (presumably businesspeople or those closely associated with them); they constitute 9 percent of the adult population of the United States; “Social Conservatives,” who are conservative on issues ranging from abortion to gay marriage and express some “skepticism” about the world of business; they constitute 11 percent of the adult population; and “Pro-Government Conservatives,” who by definition support the government and stand out for their strong religious faith and conservative views on moral issues; they make up 9 percent of the population. The Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, “The 2005 Political Typology” (May 10, 2005), 53–55.

52.

Sidney Blumenthal,

The Rise of the Counter-Establishment: From Conservative Ideology to Political Power

(New York: Perennial Library, 1988), 6.

53.

John W. Dean, “What Is Conservatism?,”

FindLaw’s Writ

(December 17, 2004) at http://writ.news.findlaw.com/scripts/printer_friendly.pl?page=/dean/20041217.html. This column was based on analysis of all the key conservative think-tank Web sites.

54.

While it is a crude test of the bipolar world of conservative journals, an electronic search of two leading conservative journals for the occurrences of key terms confirms what I have long recognized as a reader of these publications—there is conservatism and liberalism, with occasional sprinklings of “communism” and “socialism,” neither of which exists in any viable form in the United States. For example, a search of the

National Review

(from

January 22, 1988, to September 21, 2005) showed: 3,560 documents found for (conservative or conservatives or conservatism); 403 documents found for (libertarian or libertarians or libertarianism); 3,207 documents found for (liberal or liberalism); 475 documents found for (progressive or progressives or progressivism); and 26 documents found for (communitarian or communitarians or communitarianism). And a search of

Human

Events from January 1998 to September 21, 2005, showed: 4,546 documents found for (conservative or conservatives or conservatism); 207 documents found for (libertarian or libertarians or libertarianism); 3,387 documents found for (liberal or liberalism); 225 documents found for (progressive or progressives or progressivism); 155 documents found for moderate republican; and 2 documents found for (communitarian or communitarians or communitarianism).

55.

See, for example, Eric Alterman, “Fact Checking Ann Coulter” at http://www.whatliberalmedia.com/apndx_1.htm; “NY Times Praises Coulter’s Footnotes. It Should Have Looked a Few Up,”

Daily Howler

at http://www.dailyhowler.com/dh072202.shtml; a Google search of “ann coulter fact check” produced thirty-two thousand hits!