Congo (10 page)

Authors: David Van Reybrouck

As a result, Stanley’s helpers entered into real treaty-making campaigns. They went from one village chieftain to the next, armed with Leopold’s marching orders and terse contracts. Some of them lost no time in doing so. During the first six weeks of 1884, Francis Vetch, a British army major, established no less than thirty-one treaties. Belgian agents like Van Kerckhoven and Delcommune both signed nine such contracts in a single day. Within less than four years, four hundred treaties were established. They were written without exception in French or English, languages the chieftains did not understand. Within an oral tradition in which important agreements were sealed with blood brotherhood, the chiefs often did not understand the import of the cross they made at the bottom of a page filled with strange squiggles. And even if they had been able to read the texts, they would not have been familiar with concepts of European property and constitutional law like “sovereignty,” “exclusivity,” and “perpetuity.” They probably thought they were confirming ties of

friendship. But those treaties did very much indeed stipulate that they, as chieftain, surrendered all their territory, along with all subordinate rights to paths, fishing, toll keeping, and trade. In exchange for that cross the chieftains received from their new white friends bales of cloth, crates of gin, military coats, caps, knives, a livery uniform, or a coral necklace. From now on the banner of Leopold’s association would fly over their village: a blue field with a yellow star. The blue referred to the darkness in which they wandered, the yellow to the light of civilization that was now coming their way. Those are the dominant colors in the Congolese flag even today.

The reason behind Leopold’s sudden haste could be traced, once again, to rivalry among the European states. He was afraid that others would beat him to the punch. And some of them did. To the south, the Portuguese were still asserting their rights to their old colony. And to the north, Savorgnan de Brazza had begun in 1880 to establish similar treaties with local chieftains. Brazza was an Italian officer in the service of the French army, officially charged with setting up two scientific stations on the right bank of the Congo. France itself took part in the Association Internationale Africaine chaired by Leopold, and those two stations were the French contribution to the king’s initiative. But Brazza was also a fanatical French patriot who, at the behest of no nation whatsoever, was busy establishing a colony for his beloved France: it would later become the republic of Congo-Brazzaville.

32

By 1882 people in Europe had begun to realize that someone was independently buying up large sections of Central Africa. That led to great consternation. Leopold had no choice but to act.

An Italian personally buying pieces of Africa for France, and an Englishman, Stanley, buying others for the Belgian king: it was called diplomacy, but it was a gold rush. In May 1884 Brazza crossed the Congo with four canoes in an attempt to win Kinshasa for himself. But there he ran into Swinburne, the agent with whom Disasi had now been living for the last four months.

Brazza tried to make the local village chieftain a higher bid and so nullify the earlier agreement, but that resulted in an unholy row. There was a brusque discussion with Swinburne, followed by a scuffle with the chieftain’s two sons and Brazza’s hasty departure. For Leopold’s enterprise, the loss of Kinshasa would have been disastrous. It was not only the best but also the most important of his stations; it was located at a crossing of the trade routes, a place where boats moored and caravans left, where the interior communicated with the coast. The import of the incident with Brazza was almost certainly lost on Disasi, but for generations to come it remained vitally important: the area to the north and west of the river would become a French colony, known as French Congo; the area to the south would remain in Leopold’s hands.

Yet still, this episode highlighted a major weakness. In military terms, Stanley could easily deal with someone like Brazza—he had troops and Krupp cannons, while Brazza traveled virtually alone—but as long as Stanley’s outposts were not recognized by the other European powers, not a round could be fired.

33

Leopold knew that too. Starting in 1884 he devoted himself to a diplomatic offensive unparalleled in the history of the Belgian monarchy: the drive for international recognition for his private initiative in Central Africa.

Leopold cast about in search of a masterstroke. And found it.

Central Africa was at that point exciting the ambitions of many parties. Portugal and England were quibbling over who was allowed to settle where on the coast. The Swahilo-Arab traders were advancing from the east. A recently unified Germany hankered after colonial territory in Africa (and would ultimately acquire what was later Cameroon, Namibia, and Tanzania). But Leopold’s biggest rival was still France, that much was clear. That country, in the face of all expectations, had finally been rash enough to accept Brazza’s personal annexations, even though it had not asked for them in the first place. Brazza

had gone too far. Leopold could have turned his back on France in anger, but instead the king decided to calmly seize the bull by the horns. His proposal: would France allow him to go about his business in the area recently opened up by Stanley, on condition that—in the event of an eventual debacle—it be granted the

droit de préemption

(right of first refusal) over his holdings? It was an offer too good for the French to refuse. The chance that Leopold would fail, after all, was quite real. It was as though a young man had discovered an abandoned castle and set about restoring it with his own hands. To the neighbor he says: if it becomes too costly for me, you’ll have the first option! The neighbor is all too pleased to hear that. It was a brilliant

coup de poker

, and one that would also impact other parts of Europe. The agreement took Portugal down a notch or two; obstructing Leopold might mean it would suddenly find itself with mighty France as its African neighbor. The British, on the other hand, were quite charmed by the guarantee of free trade that Leopold presented so casually.

The mounting competition over Africa between European states called for a new set of rules. That was why Otto von Bismarck, master of the youngest but also the most powerful state in continental Europe, summoned the superpowers of that day to meet in Berlin. The Berlin Conference ran from November 15, 1884, to February 26, 1885. Tradition has it that Africa was divided then and there, and that Leopold had Congo tossed in his lap. Nothing, however, could be further from the truth. The conference was not the place where courtly gentlemen with compass and straightedge convivially divided African among themselves. Their aim, in fact, was the complete opposite: to open Africa up to free trade and civilization. To do that, new international agreements were needed. The drawn-out conflict between Portugal and England concerning the mouth of the Congo made that clear enough. Two important principles were established: first, a country’s claims to a territory could be based only on effective occupation (discovering an area and

leaving it to lie fallow, as Portugal had done for centuries, was no longer sufficient); second, all newly acquired areas must remain open to free international trade (no country was to be allowed to impose trade barriers, transit charges, or import or export duties). In practical terms, as Leopold would soon notice, this meant that colonization became very expensive. In order to allow free access to merchants from other countries, one had to invest a great deal in one’s effective occupation. But although the criteria of effective occupation did speed up the “scramble for Africa,” no definitive divvying up of the continent took place as of yet. The delegates to the conference met no more than ten times over a period of more than three months; Leopold himself, in fact, never made it to Berlin.

In the corridors and backrooms, however, any number of arrangements were made. Multilateral diplomacy was practiced during the plenary meetings, but bilateral diplomacy set the tone during coffee breaks. Before the conference even started, the United States recognized Leopold’s Central African claim. It accepted his flag and his authority over the newly acquired territory. Yet that sounds more impressive than it actually was. The America of that day was not the international heavyweight it would become during the twentieth century, and it had no interests whatsoever in Africa. Of much greater importance was the German stance. Bismarck considered Leopold’s plan quite insane. The Belgian king was laying claims to an area as large as Western Europe, but he held only a handful of stations along the river. It was a string of beads, with very few beads and a lot of string, to say nothing of the enormous blank spots to the left and right of it. Could this be called an “effective occupation”? But, oh well, as ruler of a little country Leopold hardly posed much of a risk. Besides, he was anything but impecunious and he

was

terribly enthusiastic. What’s more, he guaranteed free trade (something you could never be sure of with the French and Portuguese) and pledged to extend his protection to German traders in the area. After all, Bismarck figured, perhaps the

territory was indeed an ideal buffer zone between the Portuguese, French, and British claims to the region. Rather like Belgium itself in 1830, in other words, but then on a much larger scale. It might make for a bit of peace and quiet. He signed.

The other countries at the conference could do little but follow the host’s lead. Their recognition was not granted at a formal moment during the plenary session itself, but throughout the course of the conference. With the exception of Turkey, all fourteen states agreed: that included England, which had no desire to cross Germany on the eve of an important agreement concerning the Niger. Later, more or less accidentally, the conference even agreed to the vast boundaries of which Leopold had been dreaming. And so Leopold’s latest association, the Association Internationale du Congo (AIC), was internationally recognized as holding sovereign authority over an enormous section of Central Africa. The AIA had been strictly scientific-philanthropic in nature, and the CEHC commercial, but the AIC was overtly political. It possessed a tiny, but crucial, stretch of Atlantic coastline (the mouth of the Congo), a narrow corridor to the interior bordered by French and Portuguese colonies, and then an area that expanded like a funnel, thousands of kilometers to the north and south, coming to a halt only fifteen hundred kilometers (over nine hundred miles) to the east, beside the Great Lakes. It resembled a trumpet with a very short lead pipe and a very large bell. The result was a gigantic holding that was in no way in keeping with Leopold’s actual presence. The great Belgian historian Jean Stengers said: “With a bit of imagination one could compare the establishment of the state of Congo with a situation in which an individual or association would set up a number of stations along the Rhine, from Rotterdam to Basel, and thereby obtain sovereignty over all of Western Europe.”

34

At the close of the Berlin Conference, when Bismarck “contentedly hailed” Leopold’s work and extended his best wishes “for a speedy development and for the achievement of the illus

trious founder’s noble ambitions,” the audience rose to its feet and cheered for the Belgian ruler. With that applause, they celebrated the creation of the Congo Free State.

Shortly after gaining control over Congo, Leopold received a visit at his palace from a British missionary who brought with him nine black children, boys and girls of twelve or thirteen, all contemporaries of Disasi. They came from his brand-new colony and wore European clothing: dress shoes, red gloves, and a beret—their nakedness had to be covered. They were, however, allowed to sing and dance, the way they did during canoe trips. The king, his legs crossed, watched from his throne. When they were finished singing he gave each child a gold coin and paid for their journey back to London.

35

Meanwhile, ignorant of all this, Disasi Makulo was sitting on Swinburne’s veranda in Kinshasa, practicing his alphabet. The weather was lovely and cool. A slight breeze blew across the water. He saw steamboats and canoes glide across the Pool. On the far shore lay the settlement of Brazzaville, by then part of a different colony that would, from 1891 on, be called the French Congo. How his life had changed, in only eighteen months! First a child, then a slave, now a boy. No one had experienced the great course of history firsthand the way he had. He had been uprooted and borne along on the current of world politics, like a young tree by a powerful river. And it was not nearly over yet.

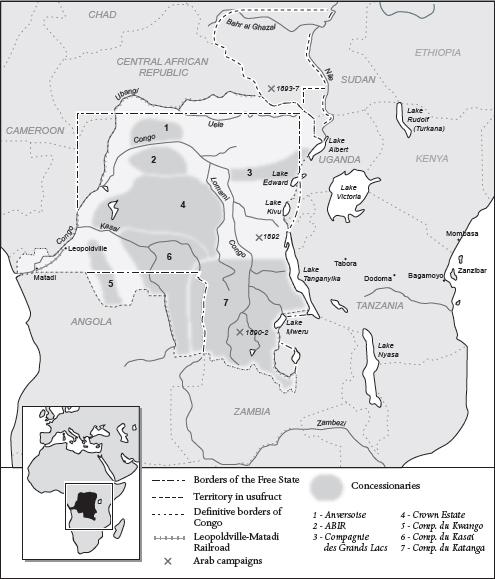

MAP 4: CONGO FREE STATE, 1885–1908

O

N

J

UNE

1, 1885, K

ING

L

EOPOLD

II

AWOKE IN HIS PALACE AT

Laeken a different man: in addition to being king of Belgium, from that day on he was also sovereign of a new state, the Congo Free State. That latter entity would continue to exist for precisely twenty-three years, five months, and fifteen days: on November 15, 1908, it was transformed into a Belgian colony. Congo began, in other words, not as a colony, but as a state, and one of the most peculiar ever seen in sub-Saharan Africa.