Colossus (46 page)

If enlargement turns out to mean that the low-productivity economies of Eastern Europe acquire both a West European welfare system and a West European currency, its macroeconomic effects could conceivably be like a slow-motion replay of German reunification, which threw millions of East Germans out of work. Productivity levels in the Czech Republic, Poland, Slovakia and Hungary are around a third of the French level. Put crudely, what this means is that unless wages in those countries are set at around a third of French levels, their workers will not be able to compete with their West European counterparts. Unfortunately, European Union labor legislation is designed to prevent what the West Europeans disingenuously label “social dumping,” a pejorative term for competition from low-wage economies. East Europeans are currently able to compensate for their low productivity by working longer hours even than Americans. The average Czech worker does more than two thousand hours of work a year, a figure that has been steadily rising since the collapse of communism, even as working hours in Western Europe have been declining. EU accession is likely to reverse that tendency, obliging Czechs to work less or not at all by giving them legal entitlements to shorter working weeks, longer holidays, stronger unions, higher minimum wages and, of course, generously funded unemployment when their employers go bust because of all this. Joining the EMU would remove the last vestige of economic flexibility, the possibility of currency depreciation.

THE RESCUE OF THE NATION - STATE CONTINUED

What, then, of Europe’s steps toward a federal constitution? Here, as always, there is a need to distinguish between rhetoric and reality. Some French and German politicians have been using the language of European federalism for years. Yet the reality has always lagged far behind, for the simple reason that the very same politicians—when it comes to actions rather than words—have consistently defended their countries’ respective national inter

ests. Alan Milward’s dictum that the first phase of European integration had more to do with the rescue of the nation-state than the construction of a federation still applies today.

66

There is little reason to think this will cease to be true even if Giscard’s constitution is eventually adopted. Indeed, a close reading of the constitution—and of comments made by the convention’s president during its deliberations—suggests that the real point of the exercise was to prevent an irrevocable swamping of the four biggest West European countries by the smaller states in the wake of eastward enlargement.

A cynic might say, for example, that the new offices of president of the European Council and EU foreign minister are the perfect jobs for a certain kind of French elder statesman—not unlike the post of president of the constitutional convention. Giscard envisaged freezing the number of European commissioners at fifteen, in other words scrapping the rule that gives each member state at least one commissioner. If that did not happen, so his argument ran, the seven smallest countries in an enlarged EU— accounting for less than 2 percent of the union’s GDP—would provide more commissioners than the six largest countries, despite the fact that the

latter group’s share of total EU output exceeds 80 percent. Giscard also raised the idea of making representation in the European Parliament more proportionate to national population sizes. “You have to take the populations into account because we operate in a democracy here,” he declared in April 2003.

67

Perhaps most important, changes to the system of qualified majority voting on the Council of Ministers would mean that EU legislation could be passed if it had the support of just half the member states, provided they represented at least 60 percent of the European Union population—a much better deal for the big four than the system agreed to at Nice in December 2000.

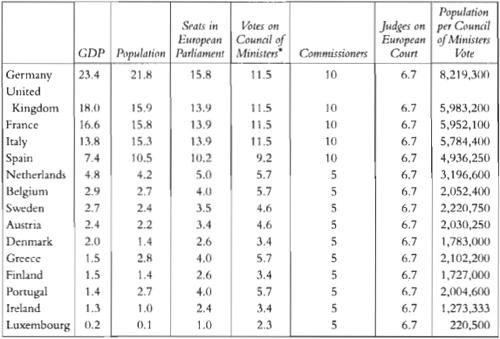

TABLE 12. THE EUROPEAN UNION IN PERCENTAGES

*System before the Nice Treaty of 2001.

Source: John McCormick,

Understanding the European Union

; OECD.

Giscard had a point. EU institutions as presently constituted do substantially overrepresent the smaller countries, as table 12 shows. For many years, this overrepresentation of the small and underrepresentation of the large has had a fiscal dimension too. Almost from its genesis in the European Coal and Steel Community (1951), the European Union has been predi

cated on transfers of resources from the larger, wealthier countries to the smaller, poorer countries. In the 1950s the inefficient Belgian coal industry received tens of millions of dollars from the other members of the ECSC, principally Germany. After the Treaty of Rome, Frances former colonies (which the French ingeniously managed to slip into the Common Market) received $380 million in development assistance from the other five signatories, again principally Germany. The Common Agricultural Policy, which by 1969 accounted for 70 percent of the European Economic Community’s budget, also effectively obliged German consumers to pay for dearer French and Dutch produce.

68

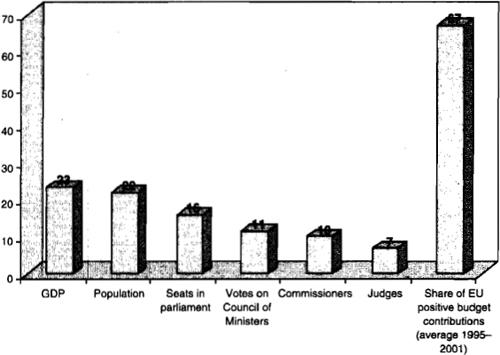

According to German budgetary data, the total amount of unrequited transfers from Germany to the other member states some years ago exceeded in nominal terms the celebrated 132 billion marks demanded of Germany by the victorious powers after the First World War.

69

FIGURE 12

Germany’s Share of European Union Resources and Institutions (Percentages)

Source: John McCormick,

Understanding the European Union

; OECD.

Yet it is inconceivable that this system can survive for very long. Apart from anything else, EU enlargement brings into the fold a number of countries markedly poorer in relative terms than any previous new members. In past enlargements the

per capita

GDP of the richest existing member—invariably Luxembourg—has been roughly two or two and a half times that of the poorest new member (Ireland in 1974, Greece in 1981, Portugal in 1986 and Finland in 1995). But the accession of the former Communist economies of Eastern Europe is an altogether bigger challenge. The average Luxembourgeois is roughly five times better off than the average Lithuanian. At Copenhagen it was agreed that the “maximum enlargement-related commitments” for the ten new states would not exceed 40.8 billion euros in the three years 2004–06. But who exactly is going to finance these transfers? It is very hard to see how German politicians can continue to justify paying the largest net contributions to the EU budget at a time when the German economy is growing so sluggishly. Clearly, German altruism has played an important role in the history of European integration since 1945. Still, there must be limits to how much more “tacit reparations” German taxpayers are willing to pay to the rest of Europe.

One little-noticed finding of recent Eurobarometer surveys is that there are significant discrepancies between the numbers of people who think the European Union is a “good thing” in general and the numbers who think it is good for their own country. There may well be a connec

tion between these discrepancies and the workings of the EU budget. In countries that are net recipients of substantial sums—Greece, Ireland and Portugal, all of which received sums greater than 2 percent of GDP between 1995 and 2001—the proportion of voters who regard the EU as good for their specific country is significantly larger than the proportion who regard it as a good thing generally. Conversely, a larger number of voters in a number of the big donor countries—Germany, Belgium and Luxembourg—regard the EU as a good thing generally than regard it as good for their own country.

70

If nothing else, that suggests a recognition on the part of voters in some, if not all, member states that there is a distinction between the European interest and the national interest.

THE LIMITS OF “EUROPEANNESS”

While it is tempting to represent “European” attitudes as increasingly “anti-American” and more self-consciously European, this is at best a caricature. First, as the Pew Center data clearly show, most Europeans draw a sharp distinction between Americans in general and the Bush administration. No less than 74 percent of French people with a negative view of the United States regard “the problem” as being “mostly Bush,” compared with just 21 percent who think it is “America in general” and 4 percent who blame both. The proportions are very similar in Germany and Italy. Secondly, and somewhat ironically, there are at least some aspects of President Bush’s foreign policy that Europeans support. Three-quarters of French, Italian and German respondents to the Pew survey agreed that the Iraqi people are better off without Saddam Hussein. Clear majorities in all the major European countries continue to favor the U.S.-led war against terrorism. More generally, there are no real transatlantic differences in attitudes toward economic and cultural globalization. It should also be noted that anti-American sentiment is not deterring young Europeans from learning the English language. Excluding Britain and Ireland, 92 percent of secondary school students in the EU are studying English—nearly three times the number studying French and seven times the number studying German.

71

At the same time, Europeans remain far less “European” than French, British, German, Italian and so on. Nine out of ten Europeans feel “fairly attached” or “very attached” to their countries. But fewer than five out of ten—45 percent—feel as “attached” to the EU. In some countries—

Sweden, Holland, Britain and Finland—between two-thirds and three-quarters of citizens describe themselves as “not very attached” or “not at all attached” to the EU. Only a tiny proportion of Europeans identify themselves exclusively as “European”; nearly half see themselves primarily as members of a traditional nationality and only secondarily as European. Moreover, the popularity of EU membership within the fifteen current members is in decline. In 1990 more than 70 percent of Europeans thought membership a good thing; the most recent surveys show a drop to just 55 percent. Just under half of Europeans regard EU membership as having “as many advantages as disadvantages.” In the light of these figures, European identity seems less than securely established.

Moreover, the impact of immigration to Europe, which will almost certainly need to continue and indeed increase to counter the rising dependency ratios discussed above, is tending to reduce rather than increase European cultural cohesion. Millions of people have moved into the European Union in the past decade, whether as economic migrants, asylum seekers or ethnic Germans. These migrants are following previous influxes, notably of former subject peoples from the defunct colonial empires in the 1960s and 1970s. According to recent estimates, between 3 and 4 percent of the populations of Holland, Germany and Britain are now Muslims; in France the proportion is nearly double that, 7.5 percent.

72

Recent trends in applications by asylum seekers and their success rates suggest that some countries are likely to end up with larger immigrant populations than others. In the years 1990 to 2000, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Austria and Sweden admitted the largest numbers relative to their respective populations. For the foreseeable future there is certain to be a profound tension between the economic need to attract more legal immigrants to Western Europe and the political antagonism toward newcomers that tends to be felt most acutely in (or close to) the relatively poor neighborhoods where they settle.

It would be an exaggeration to depict recent successes by politicians with explicitly anti-immigrant platforms as manifestations of a revival of extreme nationalist or racist politics in Europe. The politicians concerned, ranging from Jean-Marie Le Pen to Jörg Haider to the late Pim Fortuyn, have too little in common and have achieved such ephemeral successes that it would be more accurate to speak of a rash of protest votes with xeno-

phobic overtones. Still, hostility to immigrants is widespread. A survey conducted in 2000 found that more than half of Europeans think that ethnic minorities abuse national welfare systems and that immigrants increase unemployment. Nearly two-fifths think that even legal immigrants should be sent back to their countries of origin.

73

It is hardly surprising that unscrupulous populists are tempted to pander to such sentiments. The implications for those who dream of a federal Europe are dispiriting. Asked by Eurobarometer pollsters what the EU meant to them, more than a fifth of European voters checked the box marked “Not enough border controls.” Whatever restrictions are initially left in place, enlargement seems certain to heighten the perception that the EU encourages migration by creating new opportunities for young men in Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean to move westward. A few demagogues are already linking hostility to immigration and hostility to European integration. More in this vein seems almost inevitable.