Colossus (21 page)

Source: John E. Mueller,

War, Presidents and Public Opinion

, Table 3.3,

p. 54

.

THE EMPIRE STRIKES OUT

The real “lesson of Vietnam” had already been evident in Korea. But American policy makers chose to learn the wrong lessons. Not only did they resolve in future to act without the supposed encumbrance of allies and the United Nations, but they also resolved to act through proxies rather than on their own account. This made matters worse, not better. At least a Korean-style approach to the problem of Vietnam might have achieved a draw in the form of partition between North and South. An even more limited approach to imperialism was foredoomed to total failure.

There is no need here for the wisdom of hindsight. In Graham Greene’s prophetic novel

The Quiet American

, written when the United States was

still propping up the doomed French colonial regime, American attitudes toward Indochina are personified by Pyle, who fails to see that he is as much of a “colonialist” as the cynical British narrator whom he befriends (and, symbolically, cuckolds):

[Pyle] was talking about the old colonial powers—England and France, and how you couldn’t expect to win the confidence of Asiatics. That was where America came in now with clean hands.

“Hawaii, Puerto Rico,” I said. “New Mexico.”

… He said … there was always a Third Force to be found free from Communism and the taint of colonialism—national democracy he called it; you only had to find a leader and keep him safe from the old colonial powers.

153

Pyle fails to grasp that this search for indigenous collaborators is quintessentially imperial. Nor does he see that to install such a Third Force without a long-term commitment to the country is bound to end in disaster. In an attempt to convince him of this, Greene’s narrator draws an explicit parallel with the British in India and Burma: “ ‘I’ve been in India, Pyle, and I know the harm liberals do. We haven’t a liberal party any more—liberalism’s infected all the other parties. We are all either liberal conservatives or liberal socialists: we all have a good conscience…. We go and invade the country: the local tribes support us: we are victorious: but … [in Burma] we made peace … and left our allies to be crucified and sawn in two. They were innocent. They thought we’d stay. But we were liberals and we didn’t want a bad conscience.’ ”

154

Those South Vietnamese who acted on the assumption that the Americans would stay—would at least defend a partition on the Korean model—underestimated the growing power of liberalism and a bad conscience within the American elite. Even a young American officer like Philip Caputo, who openly averred that he was “battling … the new barbarians who menaced the far-flung interests of the new Rome,” did so with a strangely apologetic air:

155

“Maybe it was the effect of my grammar-school civics lessons, but I felt uneasy [searching a Vietnamese village], like a burglar or one of those bullying Redcoats who used to barge into American homes during our Revolution…. I smiled stupidly and made a great show of tidying up the mess before we left. See, lady, we’re not like the French. We’re all-American good-guy GI Joes. You should

learn to like us. We’re Yanks, and Yanks like to be liked. We’ll tear this place apart if we have to, but we’ll put everything back in its place.”

156

The effects of such imperial denial were ultimately crippling to American strategy Within a short time, the reality—that imperialists are seldom loved— began to sink in, as one disillusioned veteran put it: “We’re supposed to be saving these people and obviously we are not looked upon as the saviors here. They can’t like us a whole lot. If we came into a village, there was no flag waving, nobody running out to throw flowers at us, no pretty young girls coming out to give us kisses as we march through victorious. ‘Oh, here come the fuckng Americans again. Jesus, when are they going to learn?’ ”

157

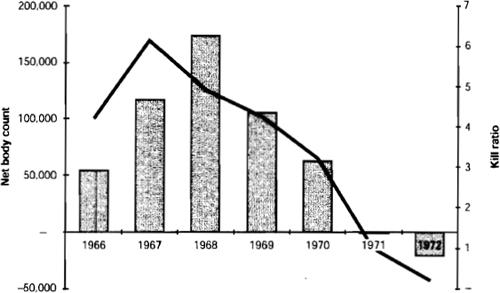

American military planners defined military success in terms of the ratio of enemy losses to their own losses; hence such grisly measures as the “net body count” and the “kill ratio” As

figure 5

shows, even by their own criteria the high point of American military success was in 1967 or 1968; by 1971 the war was clearly being lost. Of course there was an ingenuousness as well a callousness about such calculations. The reality of military success is that it is also determined by how big a proportion of each side’s manpower is being lost and, more important, by the morale of each side’s combatants and civilians. In the end, it is more important to get the other side to surrender or flee than to inflict death and wounds.

158

Over the entire period of the conflict the United States certainly inflicted higher absolute numbers of casualties on North Vietnam and the Vietcong than were suffered by American forces and the South Vietnamese. But as the American presence was scaled down in Vietnam, and as the willingness of Americans to sacrifice soldiers’ lives there diminished, so the odds tipped in favor of their more committed enemy.

Could the Vietnam War have been won if it had been fought more ruthlessly? In the eyes of many American military analysts, Vietnam exposed the flaws in the concept of limited war. General William Westmoreland, who commanded U.S. combat forces until 1968, blamed the “ill-considered” policy of “graduated response,” which he believed had prevented a swift and decisive resolution of the conflict.

159

General Bruce Palmer argued that “the graduated, piecemeal employment of airpower against North Vietnam violated many principles of war.”

160

Colonel Harry G. Summers blamed U.S. military planners for pursuing Vietcong guerrillas who were deployed to harass the U.S. Army until larger divisions from the North could be sent

down. The Americans exhausted themselves in this “counterinsurgency” effort; instead they should have driven into Laos to seal off the enemy infiltration routes running south, leaving the fight against the Vietcong to South Vietnamese troops.

161

This was a view echoed by Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger. “One of the lessons of the Vietnamese conflict,” he later wrote, “is that rather than simply counter your opponent’s thrusts, it is necessary to go for the heart of the opponent’s power; destroy his military forces rather than simply being involved endlessly in ancillary military operations.”

162

According to Admiral Thomas H. Moorer, the United States “should have fought in the north, where everyone was the enemy, where you don’t have to worry whether or not you were shooting friendly civilians…. The only reason to go to war is to overthrow a government you don’t like.”

163

FIGURE 5

The “Net Body Count” and the “Kill Ratio,” Vietnam, 1966–72

DEFINITIONS:

Net body count

(bars): North Vietnamese Army plus Vietcong killed, missing or captured in action, less American forces plus South Vietnamese Army killed, missing or captured in action.

Kill ratio

(line): North Vietnamese Army plus Vietcong killed, missing or captured in action, divided by American forces plus South Vietnamese Army killed, missing or captured in action.

Source:

http://www.vietnamwall.org/pdf/casualty.pdf

At the level of tactics too the war could have been fought more effectively American troops who had been trained to fight the Red Army in

Central Europe took time to adjust to the jungle-covered mountains and paddy fields of Vietnam, took time to learn the dark arts of war against guerrillas.

164

This process was not made easier by the demoralizing system of one-year tours of duty, which undermined unit cohesion and flattened the collective learning curve.

165

Yet ultimately the Americans did show signs of having solved the operational and tactical challenges of the war. The North Vietnamese sneered that the Americans’ “sophisticated weapons, electronic devices and the rest were to no avail” against a mobilized populace.

166

But in the final stages of the war the Americans were making devastating use of helicopter gunships, “smart” bombs and intensive bombardment by B-52s. It was this new style of air war that all but obliterated a North Vietnamese invading force at Easter 1972.

167

There were other ways the war effort could have been improved. There was not a clear chain of command: CINCPAC (commander in chief, Pacific) ran the air war on North Vietnam from Hawaii, while CO-MUSMACV (commander, U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam) ran operations in South Vietnam. Intelligence gathering could have been better.

168

Given the importance of liaison between the United States and the South Vietnamese government it was propping up, there could have been better coordination between American military leadership and American diplomatic representation.

169

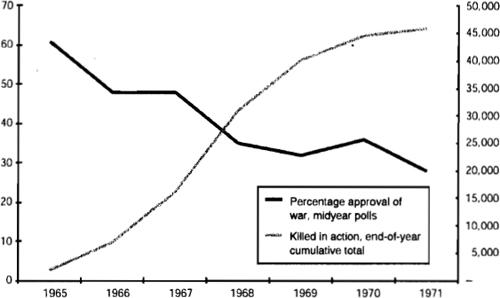

Yet even if the strategic, operational and tactical conduct of the war had been twice as effective, there was a fundamental political impediment to success: the war’s declining popularity. As early as October 1967—just two and a half years after the first marines arrived to defend Da Nang Airport

170

—more voters disapproved of the war than approved of it (see

figure 6

). The orthodox interpretation of this decline in public belligerence is that it was caused by rising American casualties. There is certainly a superficial—and indeed a statistical—correlation between the two variables.

171

Yet the determinants of popular support for war are more complex than such calculations assume. Casualties in Vietnam were not exceptionally high by comparison with other foreign wars fought by the United States. The total number of American servicemen killed in action in 1967–9,378—was less than 2.5 percent of total U.S. forces in Vietnam. In all, just 1.4 percent of the 8.7 million American military personnel who served in Southeast Asia were killed; 2.2 percent were severely disabled. The world wars were significantly more lethal. The real

problem was that by 1967 a rising proportion of Americans was doubtful that even these numbers were justified by the war’s objectives. Lack of clarity about America’s aims in Vietnam, lack of confidence that these could be achieved quickly and lack of conviction that the stated aims were worth prolonged sacrifice: these were what caused public support for the war to slide as the body count rose inexorably toward its cumulative total, which was not far short of 60,000 (of whom 47,000 were killed in action).

FIGURE 6

The Vietnam War: Casualties and Popularity

Source: John E. Mueller,

War, Presidents and Public Opinion

, Table 3.1,

p. 45f

.

It is hard to say which was cause and which was effect. Was it the declining popularity of the war that persuaded Lyndon Johnson to seek a negotiated peace, or was it the other way around? There are those who would argue that American society by the 1960s was simply incapable of pursuing such a war to a successful conclusion.

172

But there is a strong case to be made for a lack of effective political leadership. Johnson simply failed to make the case for war either to the public or to Congress.

173

Worse, as early as Christmas 1965 he embarked on a strategy of seeking peace negotiations by suspensions of the air war against Hanoi. This gambit, repeated in September 1967, proved disastrous. By indicating an American readiness

to accept a compromise peace, it encouraged the North Vietnamese to keep fighting, while creating an expectation in the United States that an end to the war was in sight. It is no coincidence that public disapproval of the war overtook public approval the following month. Yet even in early 1968 it was still not too late. More than 40 percent of voters still believed that if the United States gave up the struggle, “the Communists will take over Vietnam and then move on to other parts of the world.”

174

Lance Corporal Jack S. Swender was very far from the only American who believed it was better to “fight to stop communism in South Vietnam than in Kincaid, Humboldt, Blue Mound, or Kansas City.”

175

Westmoreland was inflicting heavy losses on the enemy as the Tet offensive foundered. The fatal mistakes were the new defense secretary Clark Clifford’s refusal to send more troops and Johnson’s decision to announce another partial bombing halt in the hope of starting talks. From this point onward American policy became a search for an honorable exit—latterly any kind of exit.