Colossus (22 page)

This was a goal which Nixon and Kissinger pursued with great ruthlessness. Secretly bombing Cambodia while secretly parleying with Le Duc Tho in Paris was doubly Machiavellian. But the position they had inherited from Johnson was beyond salvage. The cease-fire eventually signed in January 1973 was a death sentence for the South Vietnamese regime, which the Americans had originally intervened to save, while the “collateral damage” caused in Cambodia did nothing to stop that country from falling under the most brutal of all the Communist regimes in Asia. The fall of Phnom Penh to the Khmer Rouge and the flight of the last Americans from Saigon happened within days of one another in April 1975. The humiliation of American “imperialism”—a term of abuse now heard as often in the American as in the Chinese press—seemed complete. What had once been called “the white man’s burden,” as Senator J. William Fulbright lamented in January 1968, had simply been relabeled the “responsibilities of power.”

176

On balance, Americans preferred the irrespon-sibilities of weakness.

There were those who acknowledged what Greene had all along predicted: that the United States was the heir of European empire in Vietnam. “[If] this makes us the policemen of the world,” wrote platoon leader Marion Lee Kempner just three months before his death in November 1966, “then so be it. Surely this is no more a burden than the British ac

cepted from 1815 until 1915, and we have a good deal more reason to adopt it since at no time was Britain threatened during this period with total annihilation or subjection which, make no mistake about it, we are.”

177

In many other minds, however, the condition of imperial denial nevertheless persisted. Louis J. Halle insisted that America was “not fighting in Indo-China for imperialistic reasons … we are not fighting there because we want to increase our territorial possessions or build an empire.”

178

On the contrary, the Vietnam War was a simple case of mistaken identity. Kennedy and Johnson had made the tragic error of seeing the North Vietnamese regime as a mere instrument of world communism, the evil empire the United States had vowed to contain.

179

But it had turned out to be inspired more by a zealous nationalism; had not Ho Chi Minh himself approvingly cited the American Declaration of Independence?

180

The Saigon government, by contrast, had been unworthy of American support.

181

In any case, as such eminent analysts as George F. Kennan and Arthur J. Schlesinger Jr. now discerned, Indochina had been of marginal strategic significance.

182

The inference to be drawn was clear, and Nixon effectively drew it in the “doctrine” he enunciated at Guam. America should fight only when its national interests were at stake; imperiled regimes looking for U.S. sponsorship would henceforth have to do the dirty work themselves.

By the ignominious end of the American intervention in Indochina, such views were widely shared. In 1974 two-fifths of those polled agreed with the statement that “the U.S. should mind its own business internationally and let other countries get along as best they can on their own.” Ten years before, just 18 percent had thought so.

183

The consensus that had emerged by 1978 was that the Vietnam War had been “more than a mistake; it was fundamentally wrong and immoral.”

184

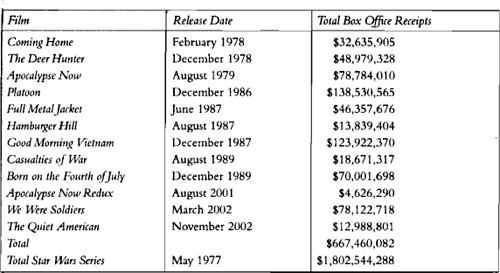

A succession of films rubbed this in. Though their budgets were large by Hollywood standards—in the case of

Apocalypse Now

fabulously so—these films proved conclusively that war films made better economic sense than actual wars. At even the most conservative estimate, the Vietnam War itself had cost over a hundred billion dollars, financed in large measure by borrowing; between 1964 and 1972 the gross federal debt had increased by roughly the same amount as had been spent on the conflict. Admittedly, that was not a huge increase in public indebtedness by comparison with what was to come in future decades. The biggest deficit of the Vietnam years was equivalent to

just over 3 percent of American GDP, less than the deficit for 2003. In that sense, Vietnam was no more crippling in terms of dollars spent than it was in terms of blood spilled. Yet the fact that so many of the dollars had to be spent abroad proved to have serious implications for what was supposed to be the anchor currency of the international monetary system devised at Bretton Woods. On August 15, 1971, a year and a half before the last American troops left Vietnam, Richard Nixon appeared to acknowledge the end of U.S. economic supremacy with his decision to “close the gold window,” ending the convertibility of the dollar and ushering a new era of floating exchange rates. Significantly, it had been European—and especially French—pressure on the dollar that had sounded the death knell for Bretton Woods, challenging (though not ending) the dollar’s status as the world’s predominant reserve currency. Failure in Vietnam did more than redefine American attitudes to the world, driving many Americans toward a repudiation of postwar globalism. It also changed the attitudes of the world toward the United States, unleashing a wave of anti-American feeling (not least within the West European intelligentsia) that was to endure for the rest of the cold war, no matter how egregious the repressiveness of Communist regimes around the world. The imperialism of anti-imperialism had come fatally unstuck if it was the United States that was cast in the role of the evil empire. Small wonder the most successful post-Vietnam movie of them all was in fact a science-fiction fable in which the audience was invited to identify with a ragtag collection of freedom fighters battling for an underdog Rebel Alliance against a sinister Galactic Empire. In

Star Wars

George Lucas perfectly expressed the American yearning not to be on the dark side of imperialism. It was not without significance that as his cinematic epic unfolded backward a generation later, the archvillain Darth Vader was revealed to have been an all-American Jedi Knight in his youth.

LITTLE CAESARS

Failure in Asia could of course be blamed on the sheer distance of Korea and Vietnam from the American mainland. Yet even in its own backyard—Latin America and the Caribbean—the United States found it surprisingly

hard to make a success of the imperialism of anti-imperialism. There were plentiful interventions. But just as in the past, where Left-wing governments were overthrown with American assistance or approval, they were generally replaced by military dictatorships whose murderous conduct did nothing to endear the United States to Hispanic-Americans. This happened in Guatemala in 1954, in the Dominican Republic in 1965 and in Chile in 1973.

185

In justifying his decision to send troops to Santo Domingo, Johnson offered the classic rhetoric of imperial denial: “Over the years of our history our forces have gone forth into many lands, but always they returned when they were no longer needed. For the purpose of America is never to suppress liberty, but always to save it. The purpose of America is never to take freedom, but always to return it; never to break peace but to bolster it, and never to seize land but always to save lives.”

186

The subsequent records of the wholly undemocratic regimes installed in each case made a mockery of these words. The most puzzling thing, however, was the failure of the United States to pull off a successful intervention in a country that was geographically nearer, economically more promising and strategically more valuable than all of these: Cuba. Not only was the United States powerless to prevent Fidel Castro’s Communist Revolution from succeeding in 1959, but two years later it failed ignominiously to pull off a countercoup by anti-Castro exiles (the Bay of Pigs fiasco), and in

October 1962 it came to the brink of a third world war when the Soviet Union sent nuclear missiles to the island.

187

Only by secretly offering to withdraw American missiles from Turkey were the Kennedy brothers able to avoid what would indeed have been “one hell of a gamble”—namely, a U.S. invasion of Cuba—and secure the peaceful withdrawal of the Soviet weapons.

188

What the Cuban missile crisis revealed was that when the two superpowers confronted each another “eyeball to eyeball,” they discovered that they had grown to resemble each other. We now know that both parties blinked in the confrontation; perhaps it was the surprise of recognition.

189

For in truth neither of the two anti-imperialist empires cared enough about Cuba to risk a thermonuclear duel. Not for the first or the last time, the principal beneficiary of this standoff was a petty dictator. So long as the superpowers could compete only through proxies, it was the little countries that got the Caesars—and, all too often, the Caligulas too.

TABLE 3. VIETNAM MOVIES—TOTAL BOX OFFICE RECEIPTS

Source:

http:/www.boxofficemojo.com

Chapter 3

The Civilization of Clashes

If the sword falls on the United States after eighty years, hypocrisy raises its head lamenting the deaths of these killers who tampered with the blood, honor, and holy places of the Muslims…. When these defended their oppressed sons, brothers, and sisters in Palestine and in many Islamic countries, the world at large shouted. The infidels shouted, followed by the hypocrites…. They champion falsehood, support the butcher against the victim, the oppressor against the innocent child…. In the aftermath of this event … every Muslim should rush to defend his religion.

OSAMA BIN LADEN, October 7, 2001

1

There is a human condition that we must worry about in times of war. There is a value system that cannot be compromised—God-given values. These aren’t United States-created values. These are values of freedom and the human condition and mothers loving their children. What’s very important as we articulate our foreign policy through our diplomacy and our military action, is that we never look like we are creating—[like] we are the author of these values.

GEORGE W. BUSH, 2002

2

TO THE HOLY LAND

Empires throughout history have sought to control certain regions of the world for the sake of their mineral wealth. It was lead and silver that lured the Romans to Britain in the first century. It was gold that lured the conquistadors to Peru in the sixteenth century and the British to the Transvaal in the nineteenth. Empires have also traditionally sought to introduce their own cultures to the countries whose minerals they have extracted. England

was Romanized just as much as the South African Rand was Anglicized. This model has suggested to many contemporary analysts that the American relationship with the Middle East has an imperial character. On the one hand, the United States has an obvious and long-standing interest in the immense oil reserves of the region. On the other, it is said, Americans aspire to transform its political culture, which has proved exceptionally resistant to democratization.

Yet if these have been the defining motivations of American policy toward the Middle East, then that policy has been very far from successful. U.S. control over Arabian oil fields declined steeply in the postwar era as a result of policies of nationalization, often adopted by overtly anti-American regimes. According to the scores awarded in the annual Freedom House survey, only Israel and Turkey—two out of the fifteen countries in the region—can be regarded as democracies today. That was also true in 1950, except that Egypt, Iran, Lebanon and Syria were all closer to political freedom then than they are today.

As the epigraphs above suggest, America’s leaders do sometimes use language that seems to confirm the allegations of their most bitter opponents in the Arab world that they are bent on a new “crusade” against Islam. In a momentary lapse President George W. Bush even used the word

crusade

himself to characterize the war he wished to wage against terrorism following the attacks of September 11, 2001. Yet the notion of a “clash of civilizations” is as much of a caricature as the idea that the United States is interested solely in the Middle East’s oil. It is rather more illuminating to conceive of the American role as that of a less than eager participant in the region’s distinctive civilization of clashes, a dysfunctional culture in which rival religions and natural resources supply much of the content of political conflict, but the

form

is the really distinctive thing. That form is of course terrorism.